According to Google’s DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) group, software delivery performance influences organizational performance in general. That means if you’re good at delivering software, you’re good at business.

In this article, we’ll discuss why the practice of using feature flags helps to become good in software delivery and then go through different ways of building a homegrown feature flagging solution. Finally, we’ll contrast the homegrown feature flagging solution with using a full-blown feature delivery platform like LaunchDarkly to help you decide whether to make that solution yourself or just buy it.

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.How Do You Become Good at Delivering Software?

So how do you become good at delivering software? The DORA group found out that the following metrics have a big impact on software delivery performance:

- Deployment frequency: the frequency in which you deploy a new version of the software you’re building. You’re good when this is measured in hours, not days or months.

- Lead time: the time it takes for the customer to request a change until the change is deployed. Since the time to design a solution is often fuzzy, the lead time is often only measured from the moment you start working on implementing the change until the change is deployed. Again, you’re good if this is measured in hours.

- Mean time to restore (MTTR): the mean of the time it takes to restore service after the service was unavailable or impacted in some way. Again, this should be measured in hours.

- Change failure rate: the percentage of deployments that cause problems and impact the service. You’re good if this is below 15%.

These metrics are the so-called “DORA metrics”. You can read everything about them in the Accelerate book written by some of the DORA researchers.

If you want to start one single practice that pushes the needle for all four DORA metrics, you should start using feature flags.

Instead of deploying a change that is visible to all customers right after deployment, you deploy the change behind a feature flag.

Only when you toggle the feature flag will the change become visible to the users. The nice thing is that feature flags don’t need to apply to all users at the same time! Instead, you could, for example, start by enabling the feature flag just for yourself to test the feature and only then enable it for a cohort of friendly users before finally enabling it for everyone.

Here’s how feature flags improve the DORA metrics:

- Feature flags improve deployment frequency because you can deploy any time. Even if there is unfinished code in the codebase, it will be hidden behind a feature flag. The main branch is always deployable.

- Feature flags improve lead time because a change can be deployed even if it’s not finished, yet, to gather feedback from key users.

- Feature flags improve the mean time to restore because you can revert a problematic change by just disabling the corresponding feature flag.

- Feature flags improve change failure rate because they decouple the risk of deployment with the risk of change. A deployment no longer fails and has to be rolled back because of bad features. The deployment is successful even if you have shipped a bad change because you can disable the bad change any time by flipping a feature flag.

If you’re still reading, you should be convinced that using feature flags is a good thing. But how to do it?

Let’s explore some ways of implementing feature flags, starting with simple if/else switches and moving up to context-sensitive feature flags that include user information when deciding to show or not show a feature to a user.

Building a Feature Flag Service

For the code examples in this article, we’ll be using Java and Spring Boot, but the concepts apply to any programming language and framework.

We’ll start by building a feature flag service that serves as the single source of truth about the state of our feature flags.

The interface looks something like this:

public interface FeatureFlagService {

Boolean featureOne();

Integer featureTwo();

}

It’s a rather simple interface with a method for each feature that we want to toggle in our application:

- feature one is a boolean flag that can be either on or off.

- feature two is a numeric flag that can have no value (

null) or a numeric value

Boolean feature flags are the most common type of feature flag and cover most use cases. I added a numeric flag as a representative to any non-boolean flag, just to show that it’s possible and how to implement it.

We can use the FeatureFlagService interface in our code to determine if a feature is active or not:

if(featureFlagService.featureOne()){

// new code

} else {

// old code

}

But where does the FeatureFlagService get the current state of the feature flags from? How does it know which feature flag is holding which value?

In the upcoming sections, we’ll implement the FeatureFlagService interface in more and more sophisticated ways to unlock more and more feature flagging use cases.

Feature Flags Backed by Code

The most straightforward solution is to implement the FeatureFlagService interface to just return hard-coded values for each feature flag:

public class CodeBackedFeatureFlagService implements FeatureFlagService {

@Override

public Boolean featureOne() {

return true;

}

@Override

public Integer featureTwo() {

return 42;

}

}

Hard-coding feature flag state defeats the main purpose of feature flags, however. We need to change the code and re-deploy if we want to enable or disable a certain feature.

Deployment and shipping of features are not decoupled with this solution! We cannot quickly disable a buggy feature in production because we have to re-deploy!

Let’s see how we can externalize the feature flag state from the code.

Feature Flags Backed by Configuration Properties

The next step in the evolution of feature flags is to externalize the feature flag state so we don’t have to change the code.

Instead of hard-coding the feature flag state, we externalize the state in a configuration file. With Spring Boot, this configuration file would be the application.yml file, for example:

features:

featureOne: true

featureTwo: 42

We can then make use of Spring Boot’s configuration properties feature to bind the feature flag state to a Java object:

@Component

@ConfigurationProperties("features")

public class FeatureProperties {

private boolean featureOne;

private int featureTwo;

// getters and setters omitted

}

This will create a FeatureProperties bean at runtime that encapsulates the state from the configuration file.

We can then inject the FeatureProperties bean in an implementation of the FeatureFlagService interface:

@Component

public class PropertiesBackedFeatureFlagService implements FeatureFlagService {

private final FeatureProperties featureProperties;

public PropertiesBackedFeatureFlagService(FeatureProperties featureProperties) {

this.featureProperties = featureProperties;

}

@Override

public Boolean featureOne() {

return featureProperties.getFeatureOne();

}

@Override

public Integer featureTwo() {

return featureProperties.getFeatureTwo();

}

}

The PropertiesBackedFeatureFlagService ultimately returns the feature flag state from the configuration file.

What did we gain by moving the feature flag state from the code to an external configuration file?

We no longer have to change and re-compile the code to change the feature flag state. If we want to change the feature flag state, we could log into a running server, change the values in the configuration file, and re-start the application. We no longer need to deploy.

However, logging into a production server to restart an application is very 90s. We don’t want to do that because it’s cumbersome and, more importantly, prone to human error. Also, in a real-world scenario, we probably have more than one application node and we don’t want to repeat the process of changing the configuration file and re-starting the application for each node!

So, what about if we store the feature flag state in a central database?

Database-Backed Feature Flags

An implementation of the FeatureFlagService interface that loads the feature flag state from the database might look something like this using Java and Spring’s JdbcTemplate:

public class DatabaseBackedFeatureFlagService implements FeatureFlagService {

private JdbcTemplate jdbcTemplate;

@Override

public Boolean featureOne() {

return jdbcTemplate.query("select value from features where feature_key='FEATURE_ONE'", resultSet -> {

if (!resultSet.next()) {

return false;

}

boolean value = Boolean.parseBoolean(resultSet.getString(1));

return value ? Boolean.TRUE : Boolean.FALSE;

});

}

@Override

public Integer featureTwo() {

return jdbcTemplate.query("select value from features where feature_key='FEATURE_TWO'", resultSet -> {

if (!resultSet.next()) {

return null;

}

return Integer.valueOf(resultSet.getString(1));

});

}

}

The DatabaseBackedFeatureFlagService requires the database table features to exist. That table has the columns feature_key and value.

Instead of a relational database like in this example, we could also use a simple key/value store.

When asked for the value of a feature flag, the service makes a call to the database and parses the value into a Boolean or Integer, as required by the feature flag. If there is no value, it returns null.

We finally have a solution that allows us to change the feature flag state on the fly! We can change the value in the database and it’s reflected instantly in the application. If all application nodes are connected against the same database, the new feature flag state is even reflected across our whole fleet of server nodes!

However, our solution only supports simple feature flag state. It can return a Boolean or Integer value for a given feature flag. If we change a feature flag value, it applies to all users. We cannot activate a feature flag for a subset of users, which is a very powerful feature to enable testing in production and progressive rollouts to more and more users, among other things.

For this, we need context-sensitive feature flags that react to the context of the user.

Context-Sensitive Feature Flags

Let’s extend our database-backed solution to make it context-sensitive so that we can target different users with different feature flag values.

Say we want to support two types of feature rollouts:

GLOBAL: the feature flag state applies to all users. This is what we’ve done in the previous sections and it’s actually not context-sensitive at all.PERCENTAGE: the feature flag state applies to a percentage of all users. We can use this for progressive rollouts, where we first enable a feature for a small percentage of users and then slowly increase the percentage (or set it back to 0 if users complain about the feature not working). This rollout strategy is context-sensitive in the sense that it knows which user it’s serving.

A naive implementation of these two rollout strategies might look like the one in this Feature class:

public class Feature {

public enum RolloutStrategy {

GLOBAL,

PERCENTAGE;

}

private final RolloutStrategy rolloutStrategy;

private final int percentage;

private final String value;

private final String defaultValue;

public Feature(RolloutStrategy rolloutStrategy, String value, String defaultValue, int percentage) {

this.rolloutStrategy = rolloutStrategy;

this.percentage = percentage;

this.value = value;

this.defaultValue = defaultValue;

}

public boolean evaluateBoolean(String userId) {

switch (this.rolloutStrategy) {

case GLOBAL:

return this.getBooleanValue();

case PERCENTAGE:

if (percentageHashCode(userId) <= this.percentage) {

return this.getBooleanValue();

} else {

return this.getBooleanDefaultValue();

}

}

return this.getBooleanDefaultValue();

}

public Integer evaluateInt(String userId) {

switch (this.rolloutStrategy) {

case GLOBAL:

return this.getIntValue();

case PERCENTAGE:

if (percentageHashCode(userId) <= this.percentage) {

return this.getIntValue();

} else {

return this.getIntDefaultValue();

}

}

return this.getIntDefaultValue();

}

double percentageHashCode(String text) {

try {

MessageDigest digest = MessageDigest.getInstance("SHA-256");

byte[] encodedhash = digest.digest(

text.getBytes(StandardCharsets.UTF_8));

double INTEGER_RANGE = 1L << 32;

return (((long) Arrays.hashCode(encodedhash) - Integer.MIN_VALUE) / INTEGER_RANGE) * 100;

} catch (NoSuchAlgorithmException e) {

throw new IllegalStateException(e);

}

}

// getters and setters omitted

}

We moved all the logic to calculate the state of a feature flag into the Feature class above. A Feature has the field rolloutStrategy, so we can choose the strategy for each feature. It also has the field percentage which defines the percentage of users for which the feature flag is active when the feature is using a PERCENTAGE rollout strategy. The field value contains the value of the feature flag to serve when the feature flag is active, and the field defaultValue contains the value to serve when the feature flag is not active.

The fun part is in the methods evaluateBoolean() and evaluateInt() which evaluate the state of a feature flag for a given userId. This userId is the context for which we evaluate the feature flag.

Both methods are very similar, with the only difference that one returns a Boolean and the other an Integer. If the rollout strategy of the feature flag is GLOBAL, we just return the value field.

If it’s a PERCENTAGE rollout strategy, we check if the hashcode of the userId (calculated by the percentageHashCode() method) is below the percentage value to determine if the feature should be active for the user or not and return the value or defaultValue accordingly.

This assumes that the percentageHashCode() method returns a different value for each user ID that is well-distributed between 0 and 100. It must always return the same value for any given user ID because we don’t want the feature state to change between two invocations of the evaluate...() method for the same user.

We then make use of the Feature class in a new implementation of the FeatureFlagService interface:

public class ContextSensitiveFeatureFlagService implements FeatureFlagService {

private final JdbcTemplate jdbcTemplate;

private final UserSession userSession;

public ContextSensitiveFeatureFlagService(JdbcTemplate jdbcTemplate, UserSession userSession) {

this.jdbcTemplate = jdbcTemplate;

this.userSession = userSession;

}

@Override

public Boolean featureOne() {

Feature feature = getFeatureFromDatabase();

if (feature == null) {

return Boolean.FALSE;

}

return feature.evaluateBoolean(userSession.getUsername());

}

@Override

public Integer featureTwo() {

Feature feature = getFeatureFromDatabase();

if (feature == null) {

return null;

}

return feature.evaluateInt(userSession.getUsername());

}

@Nullable

private Feature getFeatureFromDatabase() {

return jdbcTemplate.query("select targeting, value, defaultValue, percentage from features where feature_key='FEATURE_ONE'", resultSet -> {

if (!resultSet.next()) {

return null;

}

RolloutStrategy rolloutStrategy = Enum.valueOf(RolloutStrategy.class, resultSet.getString(1));

String value = resultSet.getString(2);

String defaultValue = resultSet.getString(3);

int percentage = resultSet.getInt(4);

return new Feature(rolloutStrategy, value, defaultValue, percentage);

});

}

}

This builds upon the DatabaseBackedFeatureFlagService we’ve built before. Instead of returning the feature flag state directly from the database, however, we map it into a Feature object and then ask that Feature object to calculate the feature flag state for a given user ID.

You can see that the implementation of both the Feature class and the ContextSensitiveFeatureFlagService contains several special cases. Actually, I don’t guarantee at all that the code above behaves as intended in all cases! Use at your own peril!

And the solution above only provides a solution for global and percentage rollouts. There is a host of other rollout strategies like rolling out by user geography, user behavior, or other demographical attributes. Also, we’d like to target specific users by their user ID so we can enable a feature for just ourselves to test in production, for example.

Also, the homegrown solution we’ve built above doesn’t provide a user interface to change feature flag state, yet! If we want to change the state of a feature flag, for example, to change the rollout percentage from 0 to 10 percent, we’d have to connect to the database and change it there. It would be nice if we had a UI to do that to make it easier and avoid errors.

All this means that you probably shouldn’t build a feature flagging solution yourself, at least not if you want to be flexible in your rollout strategies. Instead, you might want to go with a feature flagging framework like Togglz, which supports multiple rollout strategies and can store feature flag state in a database. It even provides a (simple) UI to change the state of feature flags.

Or, you use a feature management service that reduces your custom development to an absolute minimum and takes care of everything for you.

Feature Flags Backed by a Feature Management Platform

So, what would it look like if we delegate the feature flag evaluation to a full-blown feature management service like LaunchDarkly?

Something like this:

public class LaunchDarklyFeatureFlagService implements FeatureFlagService {

private final LDClient launchdarklyClient;

private final UserSession userSession;

public LaunchDarklyFeatureFlagService(LDClient launchdarklyClient, UserSession userSession) {

this.launchdarklyClient = launchdarklyClient;

this.userSession = userSession;

}

@Override

public Boolean featureOne() {

return launchdarklyClient.boolVariation("feature-one", getLaunchdarklyUserFromSession(), false);

}

@Override

public Integer featureTwo() {

return launchdarklyClient.intVariation("feature-two", getLaunchdarklyUserFromSession(), 0);

}

private LDUser getLaunchdarklyUserFromSession() {

return new LDUser.Builder(userSession.getUsername())

.build();

}

}

We’re making use of LaunchDarkly’s Java SDK, which provides the LDClient class.

To evaluate the state of a feature flag, we ask that client for the state. We can ask for a boolean value, a numeric value, or other types of values. For context, we pass in an LDUser object that is populated with the name of the user. That way, LaunchDarkly knows for which user it should evaluate the feature flag.

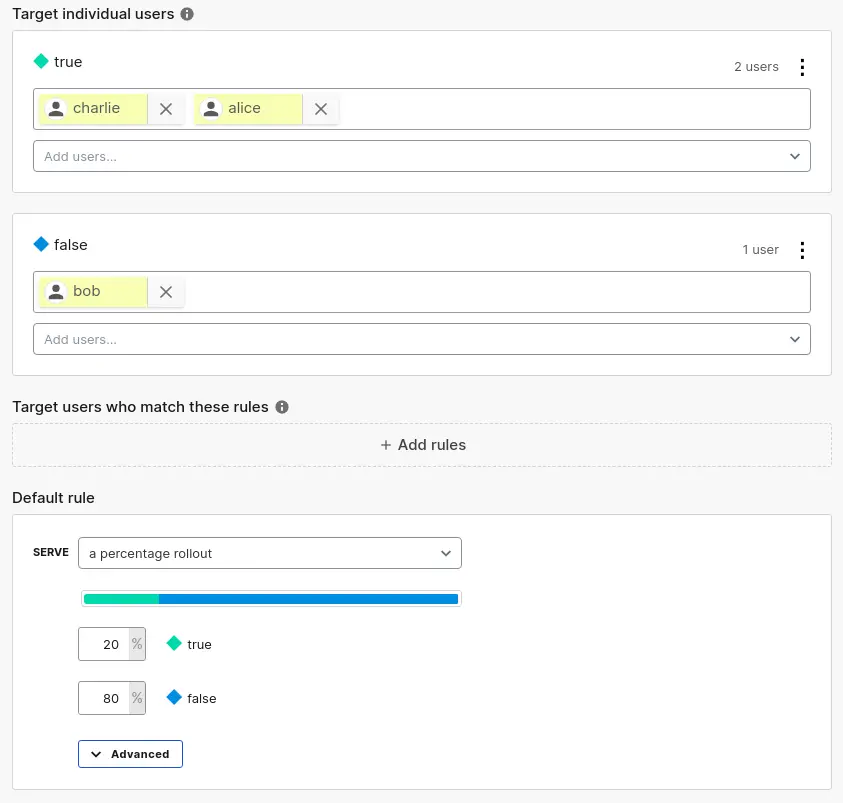

The evaluation of the feature flag then happens based on targeting rules that we have previously defined in the LaunchDarkly UI:

We can change the targeting rules at any time and the changes will have immediate effect. As long as we pass along a unique identifier for each user, LaunchDarkly takes care of resolving the correct feature flag state for that user, taking care of all edge cases for us.

If you want to play around with LaunchDarkly, have a look at my tutorial comparing Togglz with LaunchDarkly, where you’ll find a step-by-step guide on integrating LaunchDarkly with your codebase.

Conclusion

Working with feature flags is fun.

We can deploy code with “sleeping” features and enable them at any time. We gain confidence in deploying because we know the changes we’ve made will only be active once we’ve activated the feature flag.

This confidence makes us better at delivering software, as the DORA research shows without a doubt.

It’s also fun to build a homegrown solution to support feature flags in our codebase! It’s an interesting technical problem to solve.

But as soon as we want to include the user context in the decision to serve a certain feature or not, things get complicated and we’re likely to get them wrong the first time. So we should bet on solutions like Togglz or LaunchDarkly instead, so we can focus on the code that brings value to our customers.

You can browse the code examples from this article on GitHub.