Continuous Deployment is the state-of-the-art way to ship software these days. Often, however, it’s not possible to practice continuous deployment because the context doesn’t allow it (yet).

In this article, we’re going to take a look at what continuous deployment means, the benefits it brings, and what tools and practices help us to build a successful continuous delivery pipeline.

What’s Continuous Deployment?

Let’s start by discussing what “continuous deployment” means.

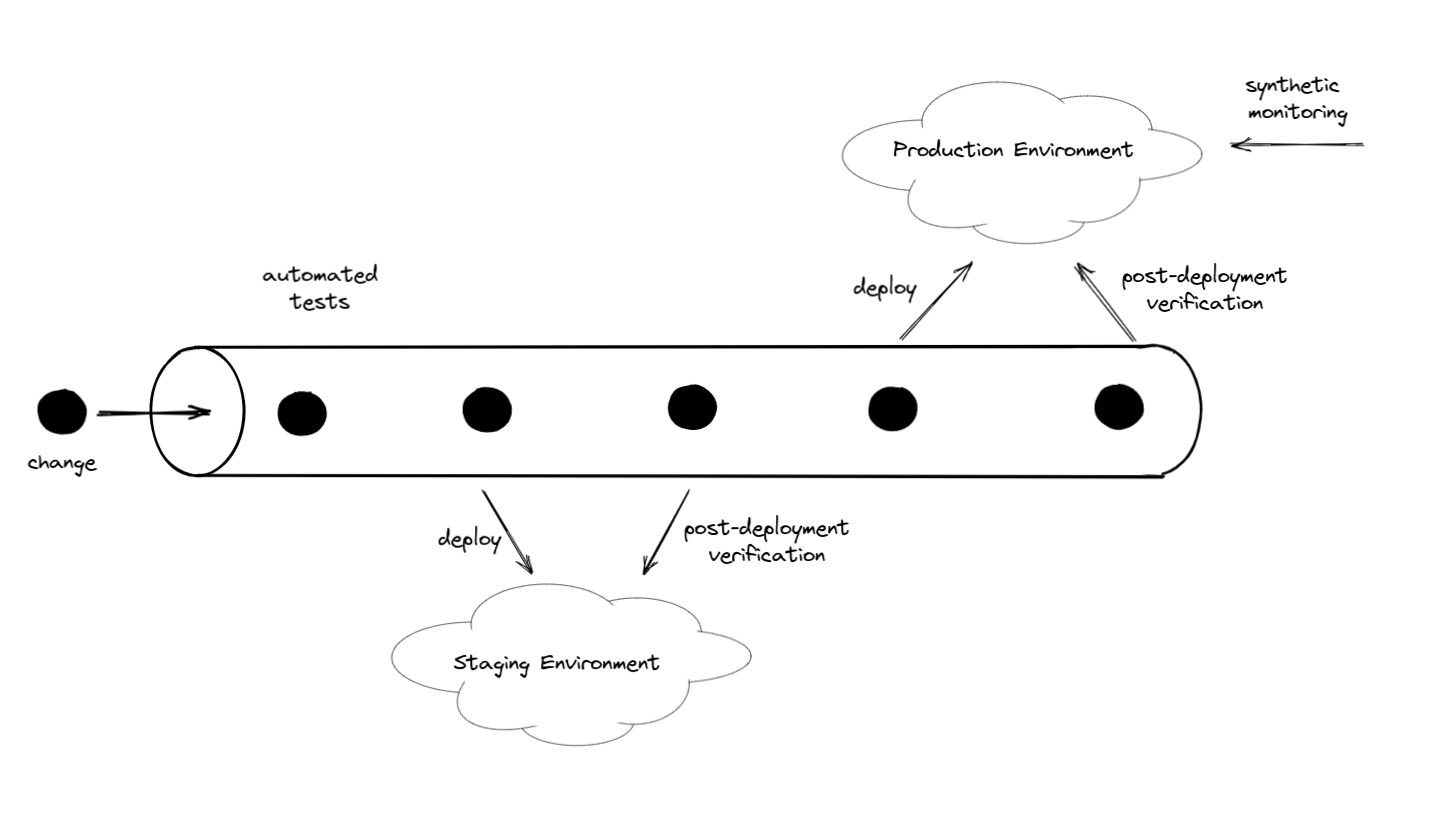

It’s often described as a pipeline that transports software changes from the developers to the production environment:

Each developer contributes changes to the pipeline, which go through a series of steps until they are automatically deployed to production.

Instead of a pipeline, we can also use the metaphor of a conveyor belt that takes the developers' changes and transports them into the production environment. Like the conveyor belt triggered the industrialization in the 20th century, we might even think of continuous deployment triggering the industrialization of software development. I don’t think we’re quite there, yet, however, because setting up a proper continuous deployment pipeline is still harder (and more expensive) than it should be, discouraging some developers and managers from implementing the practice.

In any case, the main point of continuous deployment is that we have an automated way of getting changes into production quickly and with little risk to break things in production.

It’s not enough to set up a deployment pipeline and have developers drop their changes into it. The changes could block the pipeline (a failing build, for example), or they could introduce bugs that break things in production.

Continuous deployment is all about confidence. We pass the responsibility of deploying our application to an automated system. Giving up control means that we need to be confident that this system is working. We also need to be confident that the system will notify us if something is wrong.

If we don’t have confidence in our continuous deployment systems and processes, chances are that we will want to revert to manual deployments because they give us more control.

Manual deployments, however, are proven to be slower and riskier, so we’ll want to build the most confidence-inspiring automated continuous deployment pipeline we can. And that means not only building confidence in the technical aspects of the pipeline, but also the methods and processes around it.

Continuous Integration vs. Continuous Delivery vs. Continuous Deployment

Continuous integration (CI) means that an automated system integrates the changes all developers made into the main branch regularly.

The changes in the main branch will trigger a build that compiles and packages the code and runs automated tests to check that the changes have not introduced regressions.

Continuous delivery means that the automated system also creates a deployable artifact with each run. These artifacts might be stored in a package registry as an NPM package or a Docker image, for example. We can then decide to deploy the package into production or not.

While continuous delivery ensures that we have a deployable artifact containing the latest changes from all developers at all times, continuous deployment goes a step further and ensures that the automated system deploys this artifact into production as soon as it has been created.

Without continuous integration, there is no continuous delivery and without continuous delivery, there is no continuous deployment.

Trunk-based Development

As we pointed out, continuous deployment is all about improving development velocity while keeping the risk of deploying changes to production low.

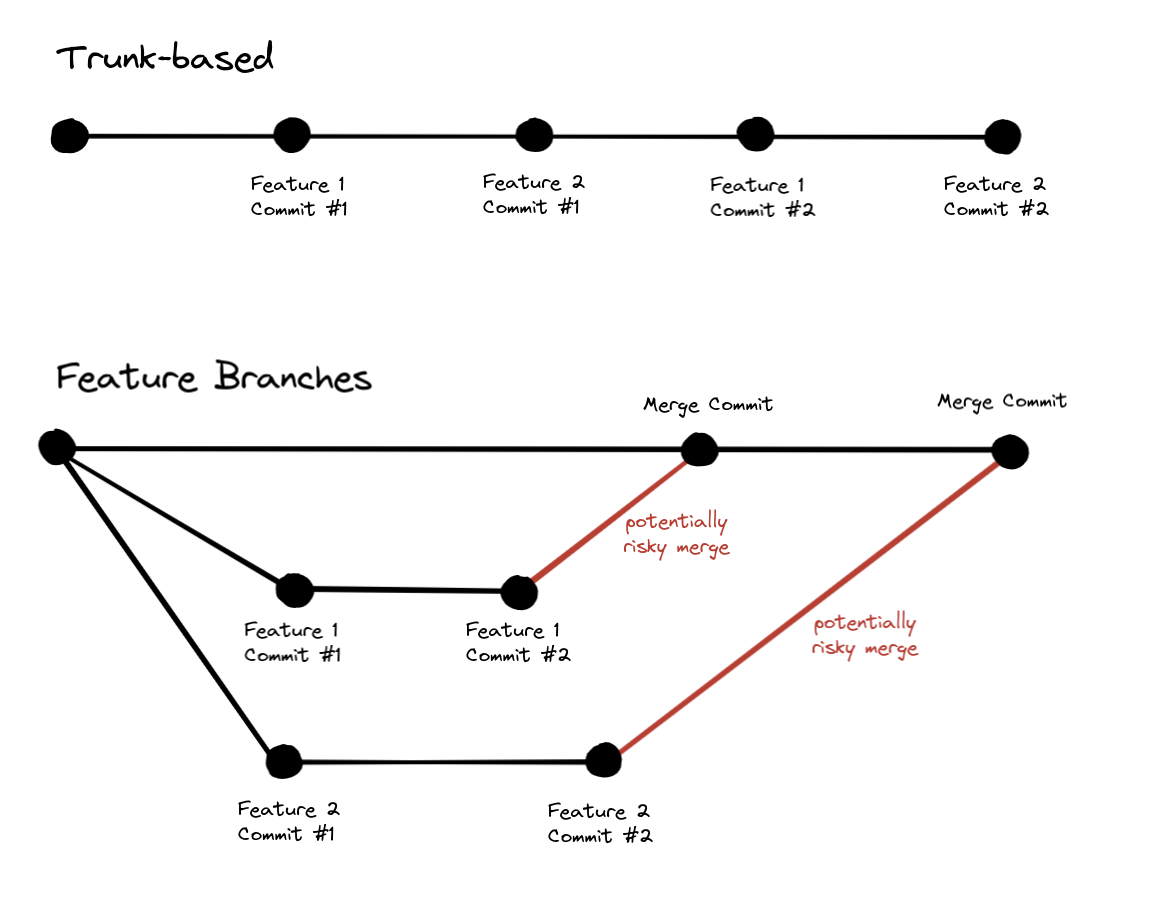

To keep the risk of changes low, the changes have to be as small as possible. A practice that directly supports small changes is trunk-based development:

Trunk-based development means that developers each contribute their changes to the main branch - the trunk, main branch, or mainline - as often as possible, making each change small enough that it can be understood and reviewed quickly. A rule of thumb is to say that each developer’s changes are merged into the main branch at least once a day.

Since each change is so small, we trust that it won’t introduce any issues so it can be automatically deployed to production by our continuous deployment pipeline.

The goal of trunk-based development is to avoid long-lived, large, and risky feature branches that require comprehensive peer reviews in favor of small iterations on the code that can be directly committed into the trunk. Practices that directly support trunk-based development are pair programming or mob programming because they have built-in peer review and knowledge sharing. That means a change can be merged into the trunk without the ritual of a separate code review.

The bigger the changes we introduce to the trunk the bigger the risk of things breaking in production, so trunk-based development forces you to do small changes and to have good review or pairing practices in place.

How does trunk-based development support continuous deployment? Trunk-based development is all about pushing small changes to the mainline continuously. Each change is so small and risk-free that we trust our automated pipeline to deploy it into production right away.

Feature Flags

Feature flags go hand in hand with trunk-based development, but they bring value even when we’re using feature branches and pull requests to merge changes into the trunk.

Since each change that we merge to the trunk is supposed to be small, we will have to commit unfinished changes. But we don’t want these unfinished changes to be visible to the users of our application, yet.

To hide certain features from users, we can introduce a feature flag. A feature flag is an if/else branch in our code that enables a certain code path only if a feature is enabled.

If we put our changes behind a disabled feature flag, we can iterate on the feature commit by commit and deploy each commit to production until the feature is complete. Then, we can enable the completed feature for the users to enjoy.

We can even decide to release the feature to certain groups of early adopters before releasing it to all users. Feature flags allow a range of different rollout strategies like a rollout to only a percentage of users or a certain cohort of users.

For example, we can only enable the feature for ourselves, so we can test the new feature in production before rolling it out to the rest of the users.

To control the state of the feature flags (enabled, disabled), we can use a feature management platform like LaunchDarkly that allows us to enable and disable a feature flag at any time, without redeploying or restarting our application.

How do feature flags support continuous deployment? Feature flags allow us to deploy unfinished changes into production. We can push small changes to production continuously and enable the feature flag once the feature is ready. We don’t need to merge long-lived feature branches that are potentially risky and might break a deployment.

Quick Code Review

To get changes into the trunk quickly and safely, it’s best to have another pair of eyes on the changes before they get merged into the trunk. There are two common approaches to getting code reviewed properly: pull requests and pair (or mob) programming.

When using pull requests, a developer has to raise a pull request with their changes. The term comes from open source development where a contributor requests the maintainers of a project to “pull” their changes into the main branch of the project.

Another developer then reviews the changes in the pull request and approves it or requires changes to the code. Finally, the pull request is merged into the main branch.

While pull requests are a great tool for distributed open-source development where strangers can contribute code, they sometimes feel like overhead in a corporate setting, where people communicate synchronously via video chat (or even in the office in real life!). In these cases, pair programming or mob programming can be an alternative.

In pair programming, we work on a change together. Since we’ve had 4 (or more) eyes on the problem the whole time, we don’t need to create a pull request that has to be reviewed but can instead merge our changes directly into the main branch.

In any case - whether we’re using pull requests or pair programming - to support continuous deployment we should make sure that we merge our changes into the main branch as quickly as possible. That means that pull requests shouldn’t wait days to be reviewed, but should be reviewed within a day at the least.

How does quick code review support continuous deployment? The longer we need to merge a change into the main branch, the more other changes will have accumulated in the meantime. Every accumulated change to the main branch might be incompatible with the change we want to merge, leading to merge conflicts, a broken deployment pipeline, or even a bad deployment that breaks a certain feature in production - all things that we want to avoid with continuous deployment.

Automated Tests

I probably don’t need to convince you to write automated tests that run with every build. It has been common practice in the industry for quite some time.

Every change we make should trigger an automated suite of tests that checks if we have introduced any regressions into the codebase. Continuous deployment can’t work without automated tests, because these tests are what give us the confidence to let a machine decide when to deploy our application.

That decision is pretty simple: if the tests were successful, deploy. If there was at least one failing test, don’t deploy. Only if the test suite is of high quality will we be confident with deploying often.

When a test is failing, the deployment pipeline is blocked. No change is going to be deployed until the test has been fixed. If it takes too long to fix the test, many other changes might have accumulated in the pipeline and one of them might have caused another test to fail, which was hidden by the first failing test.

So, if the pipeline is blocked, unblocking it is priority number one!

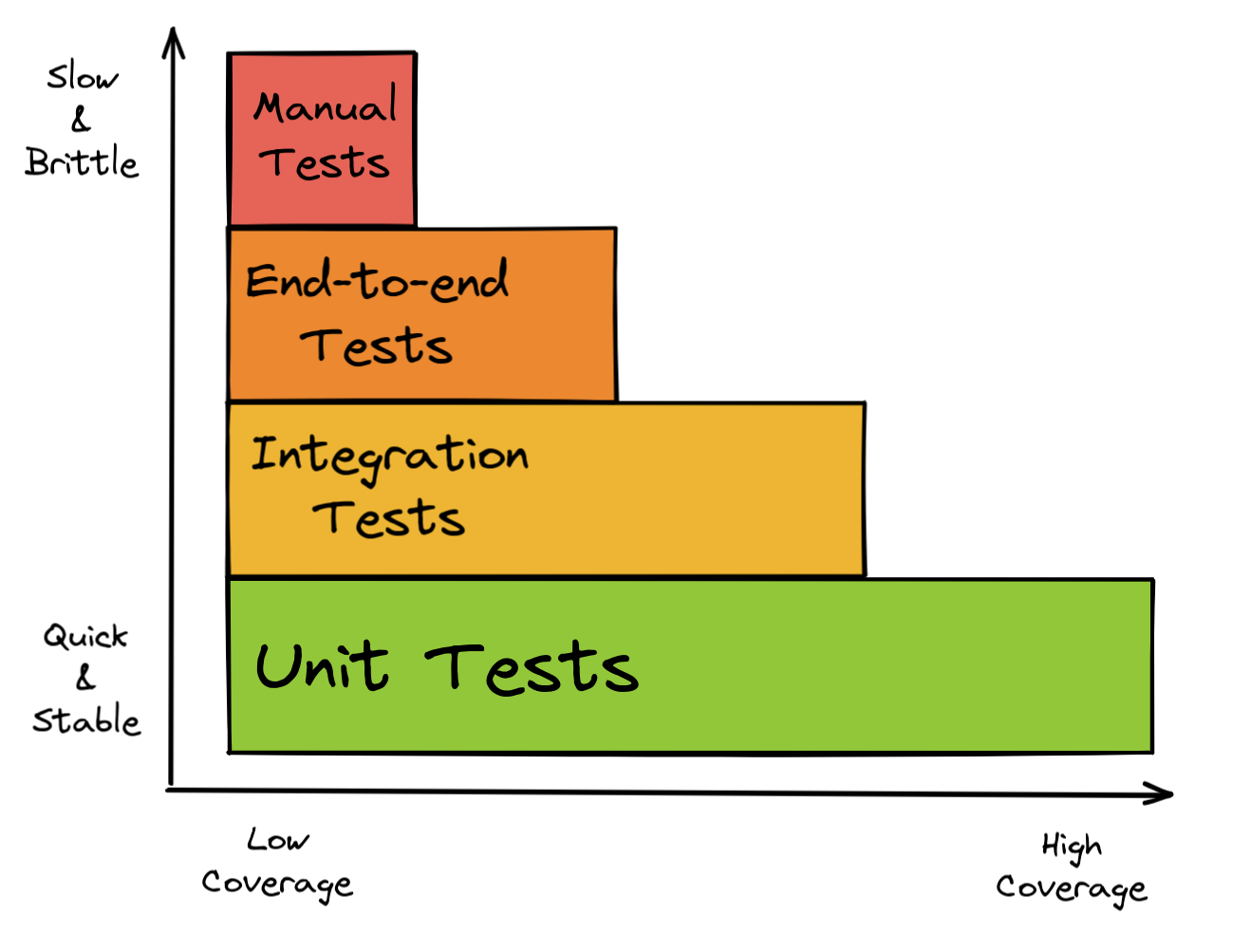

The majority of the automated tests will usually be unit tests that each cover an isolated part of the codebase (i.e. a small group of classes, a single class, or even a method). These are quick to write and relatively easy to maintain.

However, unit tests don’t prove that the “units” work well with each other, so you should at least think about adding some integration tests to your test suite. The definition of “integration test” isn’t the same in every context. They might start your application locally, send some requests against it, and then verify if the responses are as expected, for example.

It’s usually a good idea to have many cheap, quick, and stable tests (unit tests) and fewer complex, maintenance-heavy tests (manual tests) as outlined in the test pyramid:

That said, there may be arguments for an application to have no unit tests at all and instead only integration or end-to-end tests, so make your own opinion about which tests make the most sense in your context. It’s a good idea to have a testing strategy!

How do automated tests support continuous deployment? Without automated tests, we can’t have any confidence that the changes we push to production won’t break anything. A test suite with a high coverage gives us the confidence to deploy any change directly to production.

Post-Deployment Verification

We would have even more confidence in our automated deployment if our changes were automatically deployed to a staging environment and tested there before being deployed to production.

This is where post-deployment verification (PDV) tests come into play.

As the name suggests, a PDV automatically checks if everything is alright after having deployed the application. The difference to the automated tests discussed in the previous section is that post-deployment verifications run against the real application in a real environment, whereas automated tests usually run in a local environment where all external dependencies are mocked away.

That means that PDV checks can also verify if external dependencies like a database or a 3rd party service are working as expected.

As an example, a PDV could log into the application deployed on staging as a real user, trigger a few of the main use cases, and verify if the results are as expected.

With a PDV, our continuous deployment pipeline might be configured as follows:

- Run the automated tests.

- Deploy the application to the staging environment.

- Run a post-deployment verification test against the staging environment.

- If the verification was successful, deploy the application to the production environment.

- Optional: run a post-deployment verification test against the production environment.

- Optional: if the verification failed, roll the production environment back to the previous (hopefully working) version.

This way, we have a safety net built into our deployment pipeline: it will only deploy to production if the deployment to staging has proven to be successful. This alone gives us a lot of trust in the pipeline and the confidence we need to let a machine decide to deploy for us.

We can additionally add a PDV against production after a production deployment, to check that the deployment was successful, but this task can also be done by synthetic monitoring.

How does post-deployment verification support continuous deployment? Post-deployment verification adds another safety net to our deployment pipeline that helps to identify bad changes before they go into production. This gives us more confidence in our automated deployment pipeline.

Synthetic Monitoring

Once our application is deployed to a staging or production environment, how do we know that it’s still working as expected an hour after the latest change has been deployed? We don’t want to check it manually every couple of minutes, so we can set up a synthetic monitoring job that checks that for us.

Synthetic monitoring means that were are generating artificial (synthetic) traffic on our application to monitor if it’s working as expected.

A synthetic monitoring check should log into the application as a dedicated test user, run some of the main use cases, and verify that the results are as expected. If it’s failing for some reason, or not producing the expected results, it fails and alerts us that the application isn’t working as expected. A human can then investigate what’s wrong.

If we configure a synthetic monitoring check to run every couple of minutes, it gives us a lot of confidence because we know the application is working while we sleep.

As a bonus, we can re-use our post-deployment verification checks as synthetic monitoring checks!

How does synthetic monitoring support continuous deployment? With synthetic monitoring we have an additional safety net that can catch errors in the production environment before they do too much damage. Knowing that we have that safety net gives us the confidence to deploy small changes continuously.

Metrics

Say a synthetic monitoring check alerts us that something is wrong. Maybe it couldn’t finish the main use case for some reason. Is it because the cloud service we’re using failed? Is it because the queue we’re using is full? Is it because the servers ran out of memory or CPU?

We can only investigate these things if we have dashboards with some charts that show metrics like:

- successful and failing requests to the cloud service over time,

- depth of the queue over time, and

- memory and CPU consumption over time.

Having these metrics, when we get alerted, we can take a glance at the dashboards and check if there are any suspicious spikes at the time of the alert. If there are, they might lead us to the root cause of our problem.

Getting metrics like this means that our application needs to emit events that count the number of requests, for example. And our infrastructure (queues, servers) needs to emit metrics, too. These metrics should be collected in a central hub where we can view them conveniently.

How do metrics support continuous deployment? Metrics give us confidence that we can figure out the root cause when something went wrong. The more confidence, the more likely are we going to push small changes to production continuously.

Alerting and On-call

If something in our production environment goes wrong, we want to know about it before the users can even start to complain about it. That means we have to configure the system to alert us under certain conditions.

Alerting should be configured to synthetic monitoring checks and certain metrics. If a metric like CPU or memory consumption goes above or below a certain threshold for too long, it should send an alert and wake up a human to investigate and fix the problem.

Who will be notified of the alert, though? If it’s in the middle of the night, we don’t want to wake up the whole team. And anyway, if the whole team is paged, chances are that no one responds because everyone thinks someone else will do it. Alerts can have different priorities and only high-priority alerts wake people up in the middle of the night.

This is where an on-call rotation comes into play. Every week (or 2 weeks, or month), a different team member is on-call, meaning that the alerting is routed to them. They get the alert in the middle of the night, investigate the root cause, and fix it if possible. If they can’t fix the issue themselves, they alert other people who can help them. Or, they decide that the issue isn’t important enough and the fixing can wait until the next morning (in which case the alerting might need to be adjusted to not wake anyone up when this error happens the next time).

While alerting and an on-call rotation are not necessary for implementing a continuous deployment, they strongly support it. If errors in production go unnoticed because there was no alert, chances are that you lose faith in your automated deployments and revert to manual deployments.

How does alerting support continuous deployment? Knowing that we will be alerted if something goes wrong gives us yet another confidence boost that makes it easier for us to push small changes to production continuously.

Structured Logging

I probably don’t need to stress this, but proper logging makes all the difference in investigating an issue. It gives us confidence that we can figure out what’s wrong after the fact. Together with metrics dashboards, logs are a powerful observability tool.

Logs should be structured (so they’re searchable) and collected in a central log server so everyone who needs access can access them via a web interface.

While not strictly necessary for continuous deployment, knowing that we have a proper logging setup boosts our confidence so that we’re more likely to trust the continuous deployment process.

How does structured logging support continuous deployment? Similar to metrics, proper logging boosts our confidence that we can figure out the root cause when something went wrong. This gives us peace of mind to push small changes to production continuously.

Conclusion

Continuous deployment is just as much about building confidence as it is about the tooling that supports the continuous deployment pipeline.

If we don’t have confidence in our automated deployment processes, we will want to go back to manual deployments because they give us the feeling of control. And we can only have confidence if the automation works most of the time and if it alerts us when something goes wrong so we can act.

Building a continuous deployment pipeline can be a big cost, but once set up, it will save a lot of time and effort and open the way towards a DevOps culture that trusts in pushing changes to production continuously.