I recently had a rough time refactoring a multi-threaded, reactive message processor. It just didn’t seem to be working the way I expected. It was failing in various ways, each of which took me a while to understand. But it finally clicked.

This article provides a complete example of a reactive stream that processes items in parallel and explains all the pitfalls I encountered. It should be a good intro for developers that are just starting with reactive, and it also provides a working solution for creating a reactive batch processing stream for those that are looking for such a solution.

We’ll be using RxJava 3, which is an implementation of the ReactiveX specification. It should be relatively easy to transfer the code to other reactive libraries.

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.The Batch Processing Use Case

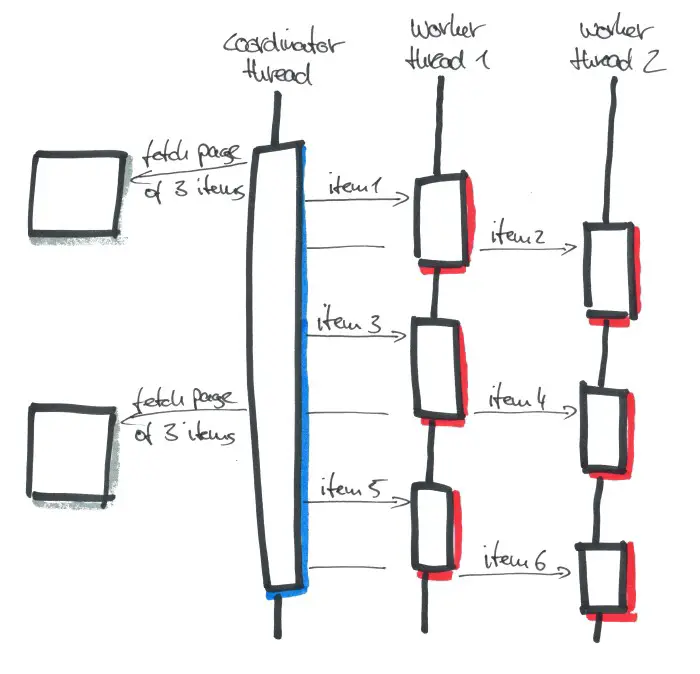

Let’s start with a literally painted picture of what we’re trying to achieve:

We want to create a paginating processor that fetches batches (or pages) of items (we’ll call them “messages”) from a source. This source can be a queue system, or a REST endpoint, or any other system providing input messages for us.

Our batch processor loads these batches of messages from a dedicated “coordinator” thread, splits the batch into single messages and forwards each single message to one of several worker threads. We want this coordination work to be done in a separate thread so that we don’t block the current thread of our application.

In the figure above, the coordinator thread loads pages of 3 messages at a time and forwards them to a thread pool of 2 worker threads to be processed. When all messages of a page have been processed, the coordinator thread loads the next batch of messages and forwards these, too. If the source runs out of messages, the coordinator thread waits for the source to generate more messages and continues its work.

In a nutshell, these are the requirements to our batch processor:

- The fetching of messages must take place in a different thread (a coordinator thread) so we don’t block the application’s thread.

- The processor can fan out the message processing to an arbitrary configurable number of worker threads.

- If the message source has more messages than our worker thread pool can handle, we must not reject those incoming messages but instead wait until the worker threads have capacity again.

Why Reactive?

So, why implement this multi-threaded batch processor in the reactive programming model instead of in the usual imperative way? Reactive is hard, isn’t it?

Hard to learn, hard to read, even harder to debug.

Believe me, I had my share of cursing the reactive programming model, and I think all of the above statements are true. But I can’t help to admire the elegance of the reactive way, especially when it’s about working with multiple threads.

It requires much less code and once you have understood it, it even makes sense (this is a lame statement, but I wanted to express my joy in finally having understood it)!

So, let’s understand this thing.

Designing a Batch Processing API

First, let’s define the API of this batch processor we want to create.

MessageSource

A MessageSource is where the messages come from:

interface MessageSource {

Flowable<MessageBatch> getMessageBatches();

}

It’s a simple interface that returns a Flowable of MessageBatch objects. This Flowable can be a steady stream of messages, or a paginated one like in the figure above, or whatever else. The implementation of this interface decides how messages are being fetched from a source.

MessageHandler

At the other end of the reactive stream is the MessageHandler:

interface MessageHandler {

enum Result {

SUCCESS,

FAILURE

}

Result handleMessage(Message message);

}

The handleMessage() method takes a single message as input and returns a success or failure Result. The Message and Result types are placeholders for whatever types our application needs.

ReactiveBatchProcessor

Finally, we have a class named ReactiveBatchProcessor that will later contain the heart of our reactive stream implementation. We’ll want this class to have an API like this:

ReactiveBatchProcessor processor = new ReactiveBatchProcessor(

messageSource,

messageHandler,

threads,

threadPoolQueueSize);

processor.start();

We pass a MessageSource and a MessageHandler to the processor so that it knows from where to fetch the messages and where to forward them for processing. Also, we want to configure the size of the worker thread pool and the size of the queue of that thread pool (a ThreadPoolExecutor can have a queue of tasks that is used to buffer tasks when all threads are currently busy).

Testing the Batch Processing API

In test-driven development fashion, let’s write a failing test before we start with the implementation.

Note that I didn’t actually build it in TDD fashion, because I didn’t know how to test this before playing around with the problem a bit. But from a didactic point of view, I think it’s good to start with the test to get a grasp for the requirements:

class ReactiveBatchProcessorTest {

@Test

void allMessagesAreProcessedOnMultipleThreads() {

int batches = 10;

int batchSize = 3;

int threads = 2;

int threadPoolQueueSize = 10;

MessageSource messageSource = new TestMessageSource(batches, batchSize);

TestMessageHandler messageHandler = new TestMessageHandler();

ReactiveBatchProcessor processor = new ReactiveBatchProcessor(

messageSource,

messageHandler,

threads,

threadPoolQueueSize);

processor.start();

await()

.atMost(10, TimeUnit.SECONDS)

.pollInterval(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS)

.untilAsserted(() ->

assertEquals(

batches * batchSize,

messageHandler.getProcessedMessages()));

assertEquals(threads, messageHandler.threadNames().size(),

String.format(

"expecting messages to be executed on %d threads!",

threads));

}

}

Let’s take this test apart.

Since we want to unit-test our batch processor, we don’t want a real message source or message handler. Hence, we create a TestMessageSource that generates 10 batches of 3 messages each and a TestMessageHandler that processes a single message by simply logging it, waiting 500ms, counting the number of messages it has processed and counting the number of threads it has been called from. You can find the implementation of both classes in the GitHub repo.

Then, we instantiate our not-yet-implemented ReactiveBatchProcessor, giving it 2 threads and a thread pool queue with capacity for 10 messages.

Next, we call the start() method on the processor, which should trigger the coordination thread to start fetching message batches from the source and passing them to the 2 worker threads.

Since none of this takes place in the main thread of our unit test, we now have to pause the current thread to wait until the coordinator and worker threads have finished their job. For this, we make use of the Awaitility library.

The await() method allows us to wait at most 10 seconds until all messages have been processed (or fail if the messages have not been processed within that time). To check if all messages have been processed, we compare the number of expected messages (batches x messages per batch) to the number of messages that our TestMessageHandler has counted so far.

Finally, after all messages have been successfully processed, we ask the TestMessageHandler for the number of different threads it has been called from to assert that all threads of our thread pool have been used in processing the messages.

Our task is now to build an implementation of ReactiveBatchProcessor that passes this test.

Implementing the Reactive Batch Processor

We’ll implement the ReactiveBatchProcessor in a couple of iterations. Each iteration has a flaw that shows one of the pitfalls of reactive programming that I fell for when solving this problem.

Iteration #1 - Working on the Wrong Thread

Let’s have a look at the first implementation to get a grasp of the solution:

class ReactiveBatchProcessorV1 {

// ...

void start() {

// WARNING: this code doesn't work as expected

messageSource.getMessageBatches()

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.from(Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor()))

.doOnNext(batch -> logger.log(batch.toString()))

.flatMap(batch -> Flowable.fromIterable(batch.getMessages()))

.flatMapSingle(m -> Single.just(messageHandler.handleMessage(m))

.subscribeOn(threadPoolScheduler(threads, threadPoolQueueSize)))

.subscribeWith(new SimpleSubscriber<>(threads, 1));

}

}

The start() method sets up a reactive stream that fetches MessageBatches from the source.

We subscribe to this Flowable<MessageBatch> on a single new thread. This is the thread I called “coordinator thread” earlier.

Next, we flatMap() each MessageBatch into a Flowable<Message>. This step allows us to only care about Messages further downstream and ignore the fact that each message is part of a batch.

Then, we use flatMapSingle() to pass each Message into our MessageHandler. Since the handler has a blocking interface (i.e. it doesn’t return a Flowable or Single), we wrap the result with Single.just(). We subscribe to these Singles on a thread pool with the specified number of threads and the specified threadPoolQueueSize.

Finally, we subscribe to this reactive stream with a simple subscriber that initially pulls enough messages down the stream so that all worker threads are busy and pulls one more message each time a message has been processed.

Looks good, doesn’t it? Spot the error if you want to make a game of it :).

The test is failing with a ConditionTimeoutException indicating that not all messages have been processed within the timeout. Processing is too slow. Let’s look at the log output:

1580500514456 Test worker: subscribed

1580500514472 pool-1-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[1-1, 1-2, 1-3]}

1580500514974 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 1-1

1580500515486 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 1-2

1580500515987 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 1-3

1580500515987 pool-1-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[2-1, 2-2, 2-3]}

1580500516487 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 2-1

1580500516988 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 2-2

1580500517488 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 2-3

...

In the logs, we see that our stream has been subscribed to on the Test worker thread, which is the main thread of the JUnit test, and then everything else takes place on the thread pool-1-thread-1.

All messages are processed sequentially instead of in parallel!

The reason (of course), is that messageHandler.handleMessage() is called in a blocking fashion. The Single.just() doesn’t defer the execution to the thread pool!

The solution is to wrap it in a Single.defer(), as shown in the next code example.

Is defer() an Anti-Pattern?

I hear people say that using defer() is an anti-pattern in reactive programming. I don't share that opinion, at least not in a black-or-white sense.

It's true that defer() wraps blocking (= not reactive) code and that this blocking code is not really part of the reactive stream. The blocking code cannot use features of the reactive programming model and thus is probably not taking full advantage of the CPU resources.

But there are cases in which we just don't need the reactive programming model - performance may be good enough without it. Think of developers implementing the (blocking) MessageHandler interface - they don't have to think about the complexities of reactive programming, making their job so much easier. I believe that it's OK to make things blocking just to make them easier to understand - assuming performance isn't an issue.

The downside of blocking code within a reactive stream is, of course, that we can run into the pitfall I described above. So, if you use blocking code withing a reactive stream, make sure to defer() it!

Iteration #2 - Working On Too Many Thread Pools

Ok, we learned that we need to defer() blocking code, so it’s not executed on the current thread. This is the fixed version:

class ReactiveBatchProcessorV2 {

// ...

void start() {

// WARNING: this code doesn't work as expected

messageSource.getMessageBatches()

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.from(Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor()))

.doOnNext(batch -> logger.log(batch.toString()))

.flatMap(batch -> Flowable.fromIterable(batch.getMessages()))

.flatMapSingle(m -> Single.defer(() ->

Single.just(messageHandler.handleMessage(m)))

.subscribeOn(threadPoolScheduler(threads, threadPoolQueueSize)))

.subscribeWith(new SimpleSubscriber<>(threads, 1));

}

}

With the Single.defer() in place, the message processing should now take place in the worker threads:

1580500834588 Test worker: subscribed

1580500834603 pool-1-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[1-1, 1-2, 1-3]}

1580500834618 pool-1-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[2-1, 2-2, 2-3]}

... some more message batches

1580500835117 pool-3-thread-1: processed message 1-1

1580500835117 pool-5-thread-1: processed message 1-3

1580500835117 pool-4-thread-1: processed message 1-2

1580500835118 pool-8-thread-1: processed message 2-3

1580500835118 pool-6-thread-1: processed message 2-1

1580500835118 pool-7-thread-1: processed message 2-2

... some more messages

expecting messages to be executed on 2 threads! ==> expected:<2> but was:<30>

This time, the test fails because the messages are processed on 30 different threads! We expected only 2 threads, because that’s the pool size we passed into the factory method threadPoolScheduler(), which is supposed to create a ThreadPoolExecutor for us. Where do the other 28 threads come from?

Looking at the log output, it becomes clear that each message is processed not only in its own thread but in its own thread pool.

The reason for this is, once again, that threadPoolScheduler() is called in the wrong thread. It’s called for each message that is returned from our message handler.

The solution is easy: store the result of threadPoolScheduler() in a variable and use the variable instead.

Iteration #3 - Rejected Messages

So, here’s the next version, without creating a separate thread pool for each message:

class ReactiveBatchProcessorV3 {

// ...

void start() {

// WARNING: this code doesn't work as expected

Scheduler scheduler = threadPoolScheduler(threads, threadPoolQueueSize);

messageSource.getMessageBatches()

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.from(Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor()))

.doOnNext(batch -> logger.log(batch.toString()))

.flatMap(batch -> Flowable.fromIterable(batch.getMessages()))

.flatMapSingle(m -> Single.defer(() ->

Single.just(messageHandler.handleMessage(m)))

.subscribeOn(scheduler))

.subscribeWith(new SimpleSubscriber<>(threads, 1));

}

}

Now, it should finally work, shouldn’t it? Let’s look at the test output:

1580501297031 Test worker: subscribed

1580501297044 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[1-1, 1-2, 1-3]}

1580501297056 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[2-1, 2-2, 2-3]}

1580501297057 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[3-1, 3-2, 3-3]}

1580501297057 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[4-1, 4-2, 4-3]}

1580501297058 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[5-1, 5-2, 5-3]}

io.reactivex.exceptions.UndeliverableException: The exception could not

be delivered to the consumer ...

Caused by: java.util.concurrent.RejectedExecutionException: Task ...

rejected from java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor@4a195f69[

Running, pool size = 2,

active threads = 2,

queued tasks = 10,

completed tasks = 0]

The test hasn’t even started to process messages and yet it fails due to an RejectedExecutionException!

It turns out that this exception is thrown by a ThreadPoolExecutor when all of its threads are busy and its queue is full. Our ThreadPoolExecutor has two threads and we passed 10 as the threadPoolQueueSize, so it has a capacity of 2 + 10 = 12. The 13th message will cause exactly the above exception if the message handler blocks the two threads long enough.

The solution to this is to re-queue a rejected task by implementing a RejectedExecutionHandler and adding this to our ThreadPoolExecutor:

class WaitForCapacityPolicy implements RejectedExecutionHandler {

@Override

void rejectedExecution(

Runnable runnable,

ThreadPoolExecutor threadPoolExecutor) {

try {

threadPoolExecutor.getQueue().put(runnable);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RejectedExecutionException(e);

}

}

}

Since a ThreadPoolExecutors queue is a BlockingQueue, the put() operation will wait until the queue has capacity again. Since this happens in our coordinator thread, no new messages will be fetched from the source until the ThreadPoolExecutor has capacity.

Iteration #4 - Works as Expected

Here’s the version that finally passes our test:

class ReactiveBatchProcessor {

// ...

void start() {

Scheduler scheduler = threadPoolScheduler(threads, threadPoolQueueSize);

messageSource.getMessageBatches()

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.from(Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor()))

.doOnNext(batch -> logger.log(batch.toString()))

.flatMap(batch -> Flowable.fromIterable(batch.getMessages()))

.flatMapSingle(m -> Single.defer(() ->

Single.just(messageHandler.handleMessage(m)))

.subscribeOn(scheduler))

.subscribeWith(new SimpleSubscriber<>(threads, 1));

}

private Scheduler threadPoolScheduler(int poolSize, int queueSize) {

return Schedulers.from(new ThreadPoolExecutor(

poolSize,

poolSize,

0L,

TimeUnit.SECONDS,

new LinkedBlockingDeque<>(queueSize),

new WaitForCapacityPolicy()

));

}

}

Within the threadPoolScheduler() method, we add our WaitForCapacityPolicy() to re-queue rejected tasks.

The log output of the test now looks complete:

1580601895022 Test worker: subscribed

1580601895039 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[1-1, 1-2, 1-3]}

1580601895055 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[2-1, 2-2, 2-3]}

1580601895056 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[3-1, 3-2, 3-3]}

1580601895057 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[4-1, 4-2, 4-3]}

1580601895058 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[5-1, 5-2, 5-3]}

1580601895558 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 1-2

1580601895558 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 1-1

1580601896059 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 1-3

1580601896059 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 2-1

1580601896059 pool-3-thread-1: MessageBatch{messages=[6-1, 6-2, 6-3]}

1580601896560 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 2-2

1580601896560 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 2-3

...

1580601901565 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 9-1

1580601902066 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 10-1

1580601902066 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 9-3

1580601902567 pool-1-thread-2: processed message 10-2

1580601902567 pool-1-thread-1: processed message 10-3

1580601902567 pool-1-thread-1: completed

Looking at the timestamps, we see that two messages are always processed at approximately the same time, followed by a pause of 500 ms. That is because our TestMessageHandler is waiting for 500 ms for each message. Also, the messages are processed by two threads in the same thread pool pool-1, as we wanted.

Also, we can see that the message batches are fetched in a single thread of a different thread pool pool-3. This is our coordinator thread.

All of our requirements are fulfilled. Mission accomplished.

Conclusion

The conclusion I draw from the experience of implementing a reactive batch processor is that the reactive programming model is very hard to grasp in the beginning and you only come to admire its elegance once you have overcome the learning curve. The reactive stream shown in this example is a very easy one, yet!

Blocking code within a reactive stream has a high potential of introducing errors with the threading model. In my opinion, however, this doesn’t mean that every single line of code should be reactive. It’s much easier to understand (and thus maintain) blocking code. We should check that everything is being processed on the expected threads, though, by looking at log output or even better, by creating unit tests.

Feel free to play around with the code examples on GitHub.