When we’re building software, we want to build for “-ilities”: understandability, maintainability, extensibility, and - trending right now - decomposability (so we can decompose a monolith into microservices if the need arises). Add your favorite “-ility” to that list.

Most - perhaps even all - of those “-ilities” go hand in hand with clean dependencies between components.

If a component depends on all other components, we don’t know what side effects a change to one component will have, making the codebase hard to maintain and even harder to extend and decompose.

Over time, the component boundaries in a codebase tend to deteriorate. Bad dependencies creep in and make it harder to work with the code. This has all kinds of bad effects. Most notably, development gets slower.

This is all the more important if we’re working on a monolithic codebase that covers many different business areas or “bounded contexts”, to use Domain-Driven Design lingo.

How can we protect our codebase from unwanted dependencies? With careful design of bounded contexts and persistent enforcement of component boundaries. This article shows a set of practices that help in both regards when working with Spring Boot.

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.Package-Private Visibility

What helps with enforcing component boundaries? Reducing visibility.

If we use package-private visibility on “internal” classes, only classes in the same package have access. This makes it harder to add unwanted dependencies from outside of the package.

So, just put all classes of a component into the same package and make only those classes public that we need outside of the component. Problem solved?

Not in my opinion.

It doesn’t work if we need sub-packages within our component.

We’d have to make classes in sub-packages public so they can be used in other sub-packages, opening them up to the whole world.

I don’t want to be restricted to a single package for my component! Maybe my component has sub-components that I don’t want to expose to the outside. Or maybe I just want to sort the classes into separate buckets to make the codebase easier to navigate. I need those sub-packages!

So, yes, package-private visibility helps in avoiding unwanted dependencies, but on its own, it’s a half-assed solution at best.

A Modular Approach to Bounded Contexts

What can we do about it? We can’t rely on package-private visibility by itself. Let’s look at an approach for keeping our codebase clean of unwanted dependencies using a smart package structure, package-private visibility where possible, and ArchUnit as an enforcer where we can’t use package-private visibility.

Example Use Case

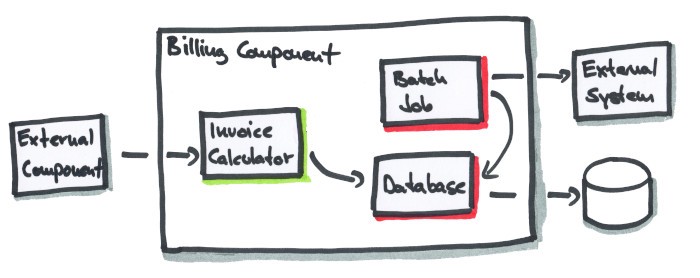

We discuss the approach alongside an example use case. Say we’re building a billing component that looks like this:

The billing component exposes an invoice calculator to the outside. The invoice calculator generates an invoice for a certain customer and time period.

To use Domain-Driven Design (DDD) language: the billing component implements a bounded context that provides billing use cases. We want that context to be as independent as possible from other bounded contexts. We’ll use the terms “component” and “bounded context” synonymously in the rest of the article.

For the invoice calculator to work, it needs to synchronize data from an external order system in a daily batch job. This batch job pulls the data from an external source and puts it into the database.

Our component has three sub-components: the invoice calculator, the batch job, and the database code. All of those components potentially consist of a couple of classes. The invoice calculator is a public component and the batch job and database components are internal components that should not be accessible from outside of the billing component.

API Classes vs. Internal Classes

Let’s take at the look at the package structure I propose for our billing component:

billing

├── api

└── internal

├── batchjob

| └── internal

└── database

├── api

└── internal

Each component and sub-component has an internal package containing, well, internal classes, and an optional api package containing - you guessed right - API classes that are meant to be used by other components.

This package separation between internal and api gives us a couple of advantages:

- We can easily nest components within one another.

- It’s easy to guess that classes within an

internalpackage are not to be used from outside of it. - It’s easy to guess that classes within an

internalpackage may be used from within its sub-packages. - The

apiandinternalpackages give us a handle to enforce dependency rules with ArchUnit (more on that later). - We can use as many classes or sub-packages within an

apiorinternalpackage as we want and we still have our component boundaries cleanly defined.

Classes within an internal package should be package-private if possible. But even if they are public (and they need to be public if we use sub-packages), the package structure defines clean and easy to follow boundaries.

Instead of relying on Java’s insufficient support of package-private visibility, we have created an architecturally expressive package structure that can easily be enforced by tools.

Now, let’s look into those packages.

Inverting Dependencies to Expose Package-Private Functionality

Let’s start with the database sub-component:

database

├── api

| ├── + LineItem

| ├── + ReadLineItems

| └── + WriteLineItems

└── internal

└── o BillingDatabase

+ means a class is public, o means that it’s package-private.

The database component exposes an API with two interfaces ReadLineItems and WriteLineItems, which allow to read and write line items from a customer’s order from and to the database, respectively. The LineItem domain type is also part of the API.

Internally, the database sub-component has a class BillingDatabase which implements the two interfaces:

@Component

class BillingDatabase implements WriteLineItems, ReadLineItems {

...

}

There may be some helper classes around this implementation, but they’re not relevant to this discussion.

Note that this is an application of the Dependency Inversion Principle.

Instead of the api package depending on the internal package, the dependency is the other way around. This gives us the freedom to do in the internal package whatever we want, as long as we implement the interfaces in the api package.

In the case of the database sub-component, for instance, we don’t care what database technology is used to query the database.

Let’s have a peek into the batchjob sub-component, too:

batchjob

└── internal

└── o LoadInvoiceDataBatchJob

The batchjob sub-component doesn’t expose an API to other components at all. It simply has a class LoadInvoiceDataBatchJob (and potentially some helper classes), that loads data from an external source on a daily basis, transforms it, and feeds it into the billing component’s database via the WriteLineItems interface:

@Component

@RequiredArgsConstructor

class LoadInvoiceDataBatchJob {

private final WriteLineItems writeLineItems;

@Scheduled(fixedRate = 5000)

void loadDataFromBillingSystem() {

...

writeLineItems.saveLineItems(items);

}

}

Note that we use Spring’s @Scheduled annotation to regularly check for new items in the billing system.

Finally, the content of the top-level billing component:

billing

├── api

| ├── + Invoice

| └── + InvoiceCalculator

└── internal

├── batchjob

├── database

└── o BillingService

The billing component exposes the InvoiceCalculator interface and Invoice domain type. Again, the InvoiceCalculator interface is implemented by an internal class, called BillingService in the example. BillingService accesses the database via the ReadLineItems database API to create a customer invoice from multiple line items:

@Component

@RequiredArgsConstructor

class BillingService implements InvoiceCalculator {

private final ReadLineItems readLineItems;

@Override

public Invoice calculateInvoice(

Long userId,

LocalDate fromDate,

LocalDate toDate) {

List<LineItem> items = readLineItems.getLineItemsForUser(

userId,

fromDate,

toDate);

...

}

}

Now that we have a clean structure in place, we need dependency injection to wire it all together.

Wiring It Together with Spring Boot

To wire everything together to an application, we make use of Spring’s Java Config feature and add a Configuration class to each module’s internal package:

billing

└── internal

├── batchjob

| └── internal

| └── o BillingBatchJobConfiguration

├── database

| └── internal

| └── o BillingDatabaseConfiguration

└── o BillingConfiguration

These configurations tell Spring to contribute set of Spring beans to the application context.

The database sub-component configuration looks like this:

@Configuration

@EnableJpaRepositories

@ComponentScan

class BillingDatabaseConfiguration {

}

With the @Configuration annotation, we’re telling Spring that this is a configuration class that contributes Spring beans to the application context.

The @ComponentScan annotation tells Spring to include all classes that are in the same package as the configuration class (or a sub-package) and annotated with @Component as beans into the application context. This will load our BillingDatabase class from above.

Instead of @ComponentScan, we could also use @Bean-annotated factory methods within the @Configuration class.

Under the hood, to connect to the database, the database module uses Spring Data JPA repositories. We enable these with the @EnableJpaRepositories annotation.

The batchjob configuration looks similar:

@Configuration

@EnableScheduling

@ComponentScan

class BillingBatchJobConfiguration {

}

Only the @EnableScheduling annotation is different. We need this to enable the @Scheduled annotation in our LoadInvoiceDataBatchJob bean.

Finally, the configuration of the top-level billing component looks pretty boring:

@Configuration

@ComponentScan

class BillingConfiguration {

}

With the @ComponentScan annotation, this configuration makes sure that the sub-component @Configurations are picked up by Spring and loaded into the application context together with their contributed beans.

With this, we have a clean separation of boundaries not only in the dimension of packages but also in the dimension of Spring configurations.

This means that we can target each component and sub-component separately, by addressing its @Configuration class. For example, we can:

- Load only one (sub-)component into the application context within a

@SpringBootTestintegration test. - Enable or disable specific (sub-)components by adding a

@Conditional...annotation to that sub-component’s configuration. - Replace the beans contributed to the application context by a (sub-)component without affecting other (sub-)components.

We still have a problem, though: the classes in the billing.internal.database.api package are public, meaning they can be accessed from outside of the billing component, which we don’t want.

Let’s address this issue by adding ArchUnit to the game.

Enforcing Boundaries with ArchUnit

ArchUnit is a library that allows us to run assertions on our architecture. This includes checking if dependencies between certain classes are valid or not according to rules we can define ourselves.

In our case, we want to define the rule that all classes in an internal package are not used from outside of this package. This rule would make sure that classes within the billing.internal.*.api packages are not accessible from outside of the billing.internal package.

Marking Internal Packages

To have a handle on our internal packages when creating architecture rules, we need to mark them as “internal” somehow.

We could do it by name (i.e. consider all packages with the name “internal” as internal packages), but we also might want to mark packages with a different name, so we create the @InternalPackage annotation:

@Target(ElementType.PACKAGE)

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

@Documented

public @interface InternalPackage {

}

In all our internal packages, we then add a package-info.java file with this annotation:

@InternalPackage

package io.reflectoring.boundaries.billing.internal.database.internal;

import io.reflectoring.boundaries.InternalPackage;

This way, all internal packages are marked and we can create rules around this.

Verifying That Internal Packages Are Not Accessed from the Outside

We now create a test that validates that the classes in our internal packages are not accessed from the outside:

class InternalPackageTests {

private static final String BASE_PACKAGE = "io.reflectoring";

private final JavaClasses analyzedClasses =

new ClassFileImporter().importPackages(BASE_PACKAGE);

@Test

void internalPackagesAreNotAccessedFromOutside() throws IOException {

List<String> internalPackages = internalPackages(BASE_PACKAGE);

for (String internalPackage : internalPackages) {

assertPackageIsNotAccessedFromOutside(internalPackage);

}

}

private List<String> internalPackages(String basePackage) {

Reflections reflections = new Reflections(basePackage);

return reflections.getTypesAnnotatedWith(InternalPackage.class).stream()

.map(c -> c.getPackage().getName())

.collect(Collectors.toList());

}

void assertPackageIsNotAccessedFromOutside(String internalPackage) {

noClasses()

.that()

.resideOutsideOfPackage(packageMatcher(internalPackage))

.should()

.dependOnClassesThat()

.resideInAPackage(packageMatcher(internalPackage))

.check(analyzedClasses);

}

private String packageMatcher(String fullyQualifiedPackage) {

return fullyQualifiedPackage + "..";

}

}

In internalPackages(), we make use of the reflections library to collect all packages annotated with our @InternalPackage annotation.

For each of these packages, we then call assertPackageIsNotAccessedFromOutside(). This method uses ArchUnit’s DSL-like API to make sure that “classes that reside outside of the package should not depend on classes that reside within the package”.

This test will now fail if someone adds an unwanted dependency to a public class in an internal package.

But we still have one problem: what if we rename the base package (io.reflectoring in this case) in a refactoring?

The test will then still pass, because it won’t find any packages within the (now non-existent) io.reflectoring package. If it doesn’t have any packages to check, it can’t fail.

So, we need a way to make this test refactoring-safe.

Making the Architecture Rules Refactoring-Safe

To make our test refactoring-safe, we verify that packages exist:

class InternalPackageTests {

private static final String BASE_PACKAGE = "io.reflectoring";

@Test

void internalPackagesAreNotAccessedFromOutside() throws IOException {

// make it refactoring-safe in case we're renaming the base package

assertPackageExists(BASE_PACKAGE);

List<String> internalPackages = internalPackages(BASE_PACKAGE);

for (String internalPackage : internalPackages) {

// make it refactoring-safe in case we're renaming the internal package

assertPackageIsNotAccessedFromOutside(internalPackage);

}

}

void assertPackageExists(String packageName) {

assertThat(analyzedClasses.containPackage(packageName))

.as("package %s exists", packageName)

.isTrue();

}

private List<String> internalPackages(String basePackage) {

...

}

void assertPackageIsNotAccessedFromOutside(String internalPackage) {

...

}

}

The new method assertPackageExists() uses ArchUnit to make sure that the package in question is contained within the classes we’re analyzing.

We do this check only for the base package. We don’t do this check for the internal packages, because we know they exist. After all, we have identified those packages by the @InternalPackage annotation within the internalPackages() method.

This test is now refactoring-safe and will fail if we rename packages as it should.

Conclusion

This article presents an opinionated approach to using packages to modularize a Java application and combines this with Spring Boot as a dependency injection mechanism and with ArchUnit to fail tests when someone has added an inter-module dependency that is not allowed.

This allows us to develop components with clear APIs and clear boundaries, avoiding a big ball of mud.

Let me know your thoughts in the comments!

You can find an example application using this approach on GitHub.

If you’re interested in other ways of dealing with component boundaries with Spring Boot, you might find the moduliths project interesting.