Most software that does more than a “hello world” needs to be configured in some way or another in order to function in a certain environment. This article explains why this configuration must not be part of the software itself, and explores some ways on how to externalize configuration parameters.

What Do We Need Configuration For?

Looking under the hood of a software project, we’ll find configuration parameters all over the place. A typical web application might need to be configured with the following parameters that may have different values for different runtime environments:

- a URL, username and password of the database to use as persistent storage

- a URL, username and password of the mail server to use for sending email

- a flag whether to disable authentication for easier testing during development

- the locale to use for date formats

- the number of seconds that web responses should be kept in the browser cache

- the logging level to decide which log messages to log and which not

- …

There’s literally no end to potential configuration parameters.

A mid-sized enterprise application might have hundreds of such configuration parameters.

Setting one of those parameters to a wrong value may lead to startup errors of the application. Or worse, the application starts up, happily serving users, and we only notice a day later that no emails have been sent and thus lost a lot of profit… .

So how do we handle those configuration parameters?

The Road to Hell: Internal Configuration

Let’s say we have two runtime environments: the production environment and a development environment used for testing.

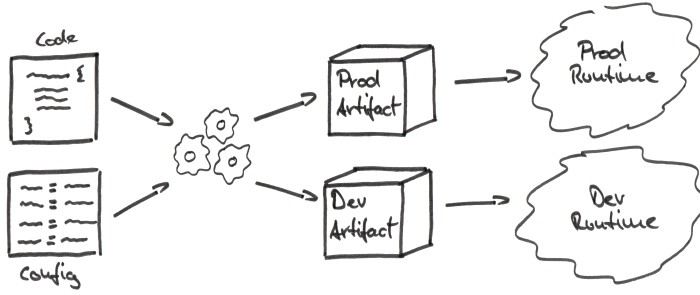

In the naive approach, we have a magic build process that takes our code and our configuration parameters for the production and development environments and creates a deployment artifact for each environment as shown in the figure below.

Since the artifacts have the configuration baked into them, they must each be deployed to the specific runtime environment they are configured for.

The configuration parameters are inside of the deployment artifact, which is why I call this internal configuration.

So what’s wrong with this approach?

First off, this approach doesn’t scale. Each time we’re changing a configuration parameter we have to re-build and re-deploy an artifact. Each time we have to wait for the build to finish before we can test the change.

Also, since we have to create a separate artifact for each runtime environment, we have to modify and test the build process each time we want to support a new runtime environment.

Another major drawback is that we’re testing one artifact in the development environment and then deploying another artifact to the production environment. Who can say what bugs are hidden in the untested production artifact?

Basically, it all boils down to this approach being a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle. This principle says that a unit of code should have as few reasons to change as possible.

If we transfer this principle to our deployment artifact, we see that our deployment artifact simply has too many reasons to change. Any configuration parameter is such a reason. A change in any parameter inevitably leads to a new artifact.

Internal configuration comes in different flavors. It may simply be a configuration file within the deployment artifact.

Even more evil is a build process that changes compiled code (or even worse: source code) during the build, depending on the target environment.

A clear indicator for internal configuration is when the build process takes a parameter that specifies a certain runtime environment.

External Configuration to the Rescue

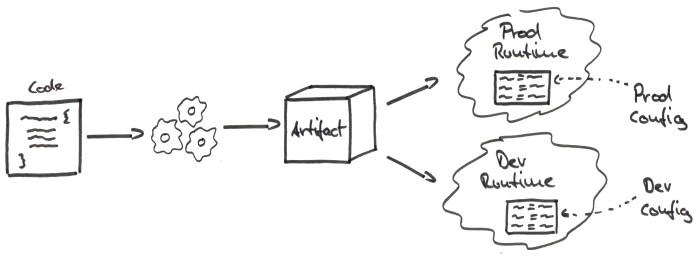

We can do better and gain a lot of flexibility by externalizing our configuration as depicted below.

Our build process no longer needs to know about the runtime environments, since we’re deploying the same artifact in all environments.

Within each environment lives a configuration that is valid for this environment only. This configuration is passed into the application at startup.

This approach negates all drawbacks of internal configuration discussed above.

Once we have tested the artifact in the development environment, we know that it will work in the production environment since we’re deploying the same artifact.

Also, we don’t have to change the build process anymore when we want to support a new environment.

We successfully have reduced the responsibilities of our deployment artifact since it doesn’t need to change for each and every configuration parameter anymore.

Let’s dive into a couple ways how we can externalize our configuration parameters.

Fixed-Location Configuration Files

The easiest way to migrate from an internal configuration file to external configuration is by simply removing the file from the deployment artifact and making it available in the file system of the target environment.

We can put the file in a fixed location that is the same in all environments, for example, “/etc/myapp.conf”.

In our code, we can load the file from this location and read the configuration parameters from it. If the file doesn’t exist, we should make sure that the application doesn’t start at all in order to keep chaos contained.

Command-Line Parameters

Another simple approach is to pass command-line parameters into our application. For every configuration parameter we have, we expect a certain command-line parameter.

This approach is more flexible than the configuration file approach since we’re no longer expecting a file to be available in a certain fixed location. But a command may grow rather long with a lot of configuration parameters.

Environment Variables

A common approach to getting rid of long command-line parameter lists is to move the parameters into environment variables provided by the operating system.

All operating systems support environment variables. They can be set to a certain value by an easy command:

- for Unix systems using the Bourne shell:

export myparameter=myvalue - for Unix systems using the Korn shell:

myparameter=myvalue export myparameter - for Windows systems:

SET myparameter=myvalue

All major programming languages provide a way to access these environment variables from source code.

Using environment variables, we can create a start script for our application that starts the application only after all environment variables have been properly set. This script lives in each target environment with different variable values.

Configuration Servers

If we want to scale our application horizontally (i.e. add more running instances to distribute load), we probably want to configure all instances the same.

Using environment variables would mean that we have to distribute the same start script to all instances.

A change in a single configuration parameter would result in a change to the start script on all instances.

This pain can be reduced by using a configuration server. The server knows all configuration parameters for all environments and provides an API to access those parameters.

At startup, the application calls the configuration server and loads all configuration parameters it needs. We might even want to re-load configuration parameters at an interval to consider changes to the parameters during runtime since the configuration server makes it easy to change parameters at a single source.

Combine and Conquer

Each technology stack provides features that support external configuration. A very good example is Spring Boot which allows a lot of different configuration sources, loads them in a sensible priority and even allows to bind them to fields in Java objects.

Such a combination of configuration sources makes it possible to define defaults in one source (i.e. a configuration file) that can be overridden by another source (i.e. the command-line). This gives us all the flexibility we could wish for in configuring our application.

Conclusion

All configuration parameters should be held outside of our deployment artifacts to avoid multiple builds, long turnaround times and quality issues.

Configuration parameters can be externalized by using configuration files, command-line parameters or environment variables.