ArchUnit is a Java library to validate your software architecture. The library is well described in its documentation and as its fluent API is pure Java, it’s easy to explore using the code completion in the IDE.

In this article, we won’t repeat the user guide, but we’ll look at what we can achieve with ArchUnit and discuss reasons why that can be useful. We’ll also look at some usages which are not directly related to the architecture of our codebase, but are useful to prevent common errors (for example how to prevent calling a certain constructor of a class).

There’s a dedicated article that explains how ArchUnit can be used in combination with Spring Boot: Clean Architecture Boundaries with Spring Boot and ArchUnit.

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.The code examples and the code in the repository use Maven as a build tool and JUnit as testing framework. The only exception are the code examples for using ArchUnit with Scala.

Why Is Testing Your Architecture Important?

The architecture of software changes over time and that’s a perfectly valid process. Therefore, architecture tests will also change. So why validating it at all? The most obvious reason is to prevent unintended changes. Using an IDE, that can happen too easily: you start typing the name of a class and the import is added automatically. Of course, it’s fine to change an ArchUnit test when it fails. Doing that forces us to think thoroughly about the change we make.

Many of us developers have been in situations where the rational behind the software architecture was not obvious. If we create a test with a descriptive name, we create a nice piece of documentation for the future.

There are more reasons why we want to validate our architecture.

- A good architecture ensures separation of concerns, which simplifies code changes and unit testing.

- Less dependencies in the codebase make refactoring and splitting up the codebase easier.

- Respecting naming conventions makes the code easier to read and understand.

- A clean architecture can facilitate secure code.

Example: Data Encapsulation

Let’s discuss in more detail how clean architecture can improve security. Here’s a practical example of how data encapsulation can prevent data exposure and how validating dependencies can help us.

Here’s a simple REST API that returns employee data:

public record Employee(long id, String name, boolean active) { }

public class EmployeeController {

@GET()

@Path("/employees")

public Employee getEmployee() {

EmployeeService service = new EmployeeService();

return service.getEmployee();

}

}

Easy enough. However, let’s say, at a later point in time, we add one more attribute to our employee entity:

public record Employee(long id, String name, boolean active, int salary) { }

What will happen? As our API operates directly on the employee class, we’ll expose the newly added attribute in the API. That could be the desired behavior in some situations, however, we might also expose new attributes involuntarily. The salary of an employee might be confidential and be adding it to the record, we expose that information. Therefore, it’s usually better to have separate classes for internal use and the API:

public record EmployeeResponse(long id, String name, boolean active) { }

with a mapping in the service class:

public class EmployeeService {

public EmployeeResponse getEmployee() {

EmployeeDao employeeDao = new EmployeeDao();

Employee employee = employeeDao.findEmployee();

return new EmployeeResponse(

employee.id(),

employee.name(),

employee.active()

);

}

}

which we then use in the controller:

public class EmployeeController {

@GET()

@Path("/employees")

public EmployeeResponse getEmployee() {

EmployeeService service = new EmployeeService();

return service.getEmployee();

}

}

The following image visualizes the difference between the two approaches:

(1) Shows the architecture without and (2) with a service layer. To keep the architecture clean, the API layer should only access the service layer and the service layer only access the domain layer. We should avoid direct access from the API to the domain layer.

Basic ArchUnit Example

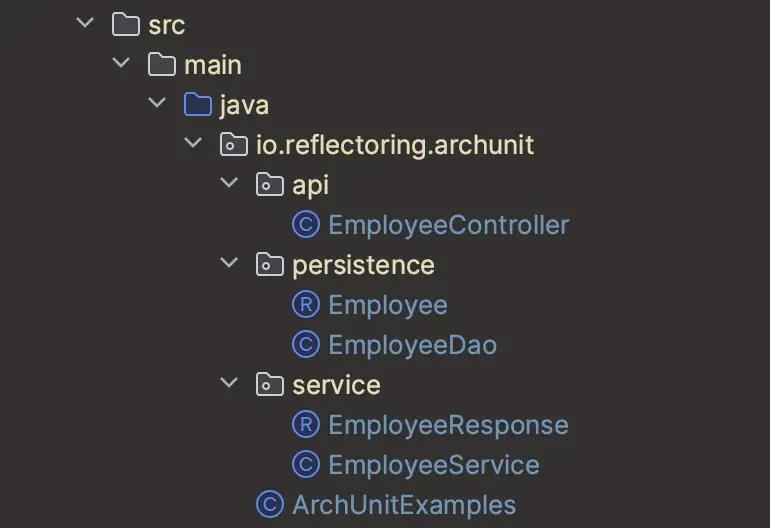

Let’s look at how we can use ArchUnit to create a test for the above example. For that, we’ll create a project with the following structure:

Our goal is to implement a test that verifies that the API layer does not access the domain layer. First, we add the ArchUnit dependency to our project:

<dependency>

<groupId>com.tngtech.archunit</groupId>

<artifactId>archunit-junit5</artifactId>

<version>1.0.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.junit.jupiter</groupId>

<artifactId>junit-jupiter-engine</artifactId>

<version>5.8.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

Then we create a unit test with an ArchUnit rule that implements the dependency check:

@Test

public void myLayerAccessTest() {

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit.api");

ArchRule apiRule= noClasses()

.should()

.accessClassesThat()

.resideInAPackage("io.reflectoring.archunit.persistence");

apiRule.check(importedClasses);

}

This test imports all classes in the io.reflectoring.archunit.api package and verifies that

there’s no dependency on any class in the persistence package. Let’s see what happens if we introduce

such a dependency:

@GET()

@Path("/employees")

public EmployeeResponse getEmployee() {

EmployeeDao dao = new EmployeeDao();

Employee employee = dao.findEmployee();

return new EmployeeResponse(

employee.id(),

employee.name(),

employee.active()

);

}

With this code, we access the persistence layer directly in the controller class. As a result, the test will fail with an assertion error, informing us about the access violation:

java.lang.AssertionError: Architecture Violation [Priority: MEDIUM]

- Rule 'no classes should access classes that reside in a package

'io.reflectoring.archunit.persistence'' was violated (2 times):

Method <io.reflectoring.archunit.api.EmployeeController.getEmployee()>

calls constructor <io.reflectoring.archunit.persistence.EmployeeDao.<init>()>

in (EmployeeController.java:15)

Method <io.reflectoring.archunit.api.EmployeeController.getEmployee()>

calls method <io.reflectoring.archunit.persistence.EmployeeDao.findEmployee()>

in (EmployeeController.java:16)

The example shows how easy it is to use ArchUnit in a Java project. Before we look at more examples, let’s discuss why architecture violations are typically introduced in projects over time.

Reasons for Architecture Erosion Over Time

There are many reasons why developers start to deviate from the initial design choices, coding best practices, or testing practices. One of the most common reasons is probably time pressure. As this is rather straightforward, we we’ll look at some other reasons in more detail.

Architecture Awareness

At the start of a software project, we usually take certain design choices and organize the code in methods, classes, packages, modules, and layers. Each of these has its specific purpose and a clear boundary. The data access layer for example should have the sole responsibility to retrieve persisted data. It should not provide an API endpoint or map data to an external format like JSON or XML.

We also make choices on certain implementation details like the inheritance (for example, every DAO class should implement an interface), or how to handle date and time in the code.

Let’s look at a simple example. Instead of:

LocalDateTime localDate = LocalDateTime.now();

we might want to use:

LocalDateTime localDate = LocalDateTime.now(clock);

When we decide to use the latter way of instantiating our object, we’ll probably remember the reason for a while. However, after some time we might forget. Also, other developers who join the project might unintentionally deviate from the original choice.

With ArchUnit, we can add a test that will fail if the static factory method now is used without the parameter:

@Test

public void instantiateLocalDateTimeWithClock() {

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit");

ArchRule rule = noClasses().should()

.callMethod(LocalDateTime.class, "now");

rule.check(importedClasses);

}

Such a test reminds the developer to use the parameter and remain consistent within the codebase. It also explains the reason why to use (or not to use) a specific method.

This is a good example of how we can use ArchUnit to document the intended architecture in the form of unit tests. Of course, we can change things when we see the need for it. There might be good reasons to deviate from a certain pattern. However, using tests as a documentation will remind us to think about why we want to deviate.

ArchUnit Examples

Most examples of how to use ArchUnit describe checks on dependencies between classes and packages. That’s however not the only use case. Let’s have a look at three other types of checks that we can create.

@deprecated

@Test

public void doNotCallDeprecatedMethodsFromTheProject() {

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit");

ArchRule rule = noClasses().should()

.dependOnClassesThat()

.areAnnotatedWith(Deprecated.class);

rule.check(importedClasses);

}

public void referenceDeprecatedClass() {

Dep dep = new Dep();

}

@Deprecated

public class Dep {

}

With this test, we can check if we still use any deprecated methods. This check can be very useful in refactoring projects where we want to upgrade the version of libraries.

BigDecimal

Another nice use case is to prevent the use of a specific constructor of a class. Why would we want to do this? IDEs usually show us a warning (including an explanation) and code quality tools such as SonarQube can be configured to detect these cases as well.

With ArchUnit, we can easily achieve this in a unit test, which makes our intention to exclude a certain constructor clear. It reminds us that we really do not want to use a specific method or constructor call and we’ll get a failed test instead of only a warning. Another benefit is, that with ArchUnit, we can introduce custom checks.

As an example, let’s see how we can prevent calling one of the constructors of the BigDecimal class:

@Test

public void doNotCallConstructor() {

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit");

ArchRule rule = noClasses().should()

.callConstructor(BigDecimal.class, double.class);

rule.check(importedClasses);

}

This test will fail if we call the BigDecimal constructor that accepts a double value as a parameter:

public void thisMethodCallsTheWrongBigDecimalConstructor() {

BigDecimal value = new BigDecimal(123.0);

}

The test will pass if we use the constructor that accepts a string instead:

BigDecimal value = new BigDecimal("123.0");

Validating Unit Tests

Another interesting use case for ArchUnit is to test the structure of unit tests themselves. Let’s look at the following two tests:

@Test

public void aTestWithAnAssertion() {

String expected = "chocolate";

String actual = "chocolate";

assertEquals(expected, actual);

}

@Test

public void aTestWithoutAnAssertion() {

String expected = "chocolate";

String actual = "chocolate";

expected.equals(actual);

}

The first test contains an assertion, while the second doesn’t. Obviously, such a test isn’t useful at all. With ArchUnit, we can go ahead and create the following rule:

public ArchCondition<JavaMethod> callAnAssertion =

new ArchCondition<>("a unit test should assert something") {

@Override

public void check(JavaMethod item, ConditionEvents events) {

for (JavaMethodCall call : item.getMethodCallsFromSelf()) {

if((call.getTargetOwner().getPackageName().equals(

org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.class.getPackageName())

&& call.getTargetOwner().getName().equals(

org.junit.jupiter.api.Assertions.class.getName()))

|| (call.getTargetOwner().getName().equals(

com.tngtech.archunit.lang.ArchRule.class.getName())

&& call.getName().equals("check"))

) {

return;

}

}

events.add(SimpleConditionEvent.violated(

item, item.getDescription() + "does not assert anything.")

);

}

};

}

@ArchTest

public void testMethodsShouldAssertSomething(JavaClasses classes) {

ArchRule testMethodRule = methods().that().areAnnotatedWith(Test.class)

.should(callAnAssertion);

testMethodRule.check(classes);

}

With this test, we make sure that all our unit tests have at least one assertion.

Sharing Tests Between Projects

ArchUnit tests are a good example of unit tests that can be shared between projects. We usually write unit tests

to test classes and methods within the same codebase. For example, we would have the following test in the library

that implements the ArrayList class:

@Test

public void testArrayList() {

List list = new ArrayList();

list.add("My item");

assertEquals(1, list.size());

}

We would not have this test in a project that only uses the library and therefore do not need to share it with other projects.

ArchUnit tests on the other hand test the structure and architecture of a project. A rule like

ArchRule interfaceName = classes().that().areInterfaces()

.should.haveNameMatching("I.*");

is a generic rule that can be reused in many projects. This approach is useful to maintain consistency between project within an organization. Especially with the shift from monolith applications to microservices, sharing ArchUnit tests can be very useful.

As ArchUnit tests are pure Java, we can use any approach of sharing tests between projects. Let’s briefly look at two ways of doing that.

Sharing as a Maven Dependency

One way of making test available to another project is to bundle them in a dedicated project and it as a dependency to the project where we want to reuse the tests. As an example, let’s create a class with one ArchUnit test:

public class ArchUnitCommonTest {

@ArchTest

public static final ArchRule bigDecimalRule = noClasses()

.should()

.callConstructor(BigDecimal.class, double.class);

}

which we add under the main Java root folder src/main/java/com/example (make sure not to add it under /src/test/java).

We can define the name of our dependency in the pom file:

<groupId>org.example</groupId>

<artifactId>BundledArchitectureTests</artifactId>

<version>1.0-SNAPSHOT</version>

And include the tests in any other project:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.example</groupId>

<artifactId>BundledArchitectureTests</artifactId>

<version>1.0-SNAPSHOT</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

Now, we can use the tests in the following way:

@AnalyzeClasses(packages = "com.example")

public class CommonTests {

@ArchTest

static final ArchTests commonRules = ArchTests.in(ArchUnitCommonTest.class);

}

The @ArchUnit annotation on the rule will run the test on all classes included by @AnalyzeClasses.

ArchUnit Maven Plugin

There’s a nice ArchUnit Maven plugin that can run ArchUnit tests included via a dependency directly on our project. The advantage over the approach above is, that we do not need to add any unit tests explicitly, but it’s all handled in the Maven pom file.

The plugin also comes with bundled tests, that can be reused and are a good inspiration to create your own tests.

For example, we can include

<rule>com.societegenerale.commons.plugin.rules.NoJavaUtilDateRuleTest</rule>

to make sure we do not use the Date class in java.util.Date in our project.

Introducing ArchUnit to an Existing Project

ArchUnit tests can easily be added to an existing codebase. We only need to add the dependency to our project and start to write the tests. If we do so, we not only ensure that future code complies to our architectural design, but we can check if the existing code does so, too! Introducing ArchUnit to an existing project can help you to really understand the architecture and find flaws in the current design.

While adding tests to your projects, you might encounter many violation which you want to fix later. ArchUnit provides a nice feature for this case: FreezeRules.

Frozen rules will be reported as passed but the violations will be stored in

a violation store. Every time, the test is run, the store is updated. The text file

can be used to monitor the progress of passing tests.

We can also implement a custom validation store, for example to save the result in

a database (by implementing com.tngtech.archunit.library.freeze.ViolationStore).

Let’s look at an example:

@Test

public void freezingRules() {

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit");

ArchRule rule = methods().that()

.areAnnotatedWith(Test.class)

.should().haveFullNameNotMatching(".*\\d+.*");

FreezingArchRule.freeze(rule).check(importedClasses);

}

This test will report a failure only once and persist the result (the default file for that is archunit_store).

For this to work, we need to set the property freeze.store.default.allowStoreCreation=true in a property file called

archunit.properties.

Successive runs will only report new failures.

Here’s an example of how rule validations are stored:

Method <io.reflectoring.archunit.ArchUnitTest.someArchitectureRule2()>

has full name matching '.*\d+.*' in (ArchUnitTest.java:28)

Method <io.reflectoring.archunit.ArchUnitTest.violatedRule1()>

has full name matching '.*\d+.*' in (ArchUnitTest.java:50)

If we want to fix already reported validations, we can remove the file or remove FreezingArchRule from our test.

ArchUnit and Other JVM Languages

As we’ve already seen, ArchUnit analyzes bytecode. That means we can - in principle - use ArchUnit for any JVM language like Kotlin, Scala, or Groovy. However, it’s not always possible to easily test for language specific features of languages other than Java. If we want to write tests for a particular JVM language, it comes in handy to know how language features are compiled to bytecode. Let’s look at some examples of using ArchUnit with Scala.

The following code snippet shows a simple test, which passes when run:

@Test

class ArchUnitTest {

@Test def verifyTheAccessModifierOfMethods(): Unit = {

val importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring")

val rule : ArchRule = methods.should.haveModifier(JavaModifier.PUBLIC)

rule.check(importedClasses)

}

}

The following test, however, will fail. That’s because a trait is compiled to a public, abstract class:

@Deprecated

private trait myTrait {

}

@Test

class ArchUnitTest {

@Test def verifyTheAccessModifierOfMethods(): Unit = {

val importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter()

.importPackages("io.reflectoring")

val rule : ArchRule = classes().that()

.areAnnotatedWith(classOf[Deprecated])

.should.haveModifier(JavaModifier.PRIVATE)

rule.check(importedClasses)

}

}

Another example of a Scala-specific language feature that cannot be tested out of the box are Scala objects and companion objects.

This works:

val rule: ArchRule = classes().that()

.areInterfaces()

.should.haveNameMatching("I.*")

However, the following methods are not provided by ArchUnit:

val objectsRule: ArchRule = classes().that()

.areObjects().should.haveNameMatching("I.*")

val companionRule: ArchRule = classes().that()

.areCompanionObjects().should.haveNameMatching("CO.*")

Despite these limitation, ArchUnit can be used with other JVM languages and if we are aware of some pitfalls, it makes ArchUnit a good choice for all JVM languages. This is the benefit of analyzing the bytecode.

Limitations

As ArchUnit analyzes the generated bytecode, we cannot write tests for language features that are not reflected in the bytecode:

ArchRule listParameterTypeRule = methods().should()

.haveRawParameterTypes(List.class);

ArchRule listReturnTypeRule = methods().should()

.haveRawReturnType(List.class);

ArchRule stringListReturnTypeRule = methods().should()

.haveRawReturnType(List<String>.class);

List<Object>

Caching

ArchUnit analyzes all classes that are imported by the ClassFileImporter. The scanning of all classes

can quite some times (especially for larger projects) and is repeated for every test when we explicitly include

the import for every test:

JavaClasses importedClasses = new ClassFileImporter().importPackages("io.reflectoring.archunit");

If we import classes using @AnalyzeClasses and annotate our tests with @ArchTest instead of @Test:

@AnalyzeClasses(packages = "io.reflectoring.archunit")

public class ArchUnitCachedTest {

@ArchTest

public void doNotCallDeprecatedMethodsFromTheProject(JavaClasses classes) {

JavaClasses importedClasses = classes;

ArchRule rule = noClasses().should()

.dependOnClassesThat().areAnnotatedWith(Deprecated.class);

rule.check(importedClasses);

}

@ArchTest

public void doNotCallConstructorCached(JavaClasses classes) {

JavaClasses importedClasses = classes;

ArchRule rule = noClasses().should()

.callConstructor(BigDecimal.class, double.class);

rule.check(importedClasses);

}

}

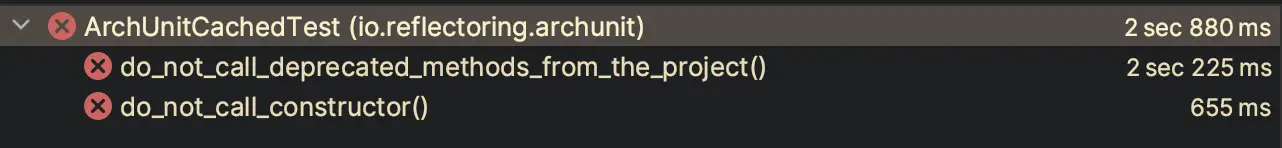

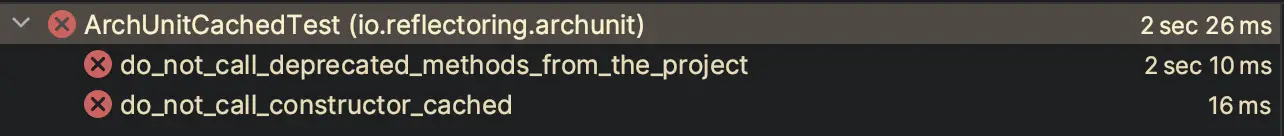

Then ArchUnit will cache the imported classes and reuse for different tests. The below screenshots shows an example of two test runs. The first image show the timings without, the second image with caching:

The second image shows that the second test executes much faster when the classes that were imported in the first test are reused.

Conclusion

With ArchUnit, we can test and document the architecture of our codebase with a clean, lightweight and pure Java library.

It’s easy to integrate ArchUnit tests into existing projects, which is a good exercise to get a good understanding of the design of an existing codebase.

The effort and risk to get started with ArchUnit in your (existing) project is very low and I highly recommend to try out the little library!