Feature flags, in their simplest form, are just if conditions in your code that check if a certain feature is enabled or not. This allows us to deploy features even when they are not ready, meaning that our codebase is always deployable. This, in turn, enables continuous deployment even while the team is continuously pushing small commits to the main branch.

More advanced feature flags allow us to target specific users. Instead of enabling a feature for everyone, we only enable it for a cohort of our users. This allows us to release a feature progressively to more and more users. If something goes wrong, it only goes wrong for a handful of users.

In this article, I want to go through some general best practices when using feature flags.

Deploy Continuously

Feature flags are one of the main enablers of continuous deployment. Using feature flags consistently, you can literally deploy any time, because all unfinished changes are hidden behind (disabled) feature flags and don’t pose a risk to your users.

Make use of the fact that you can deploy any time and implement a continuous deployment pipeline that deploys your code to production every time you push to the mainline!

Continuous deployment doesn’t mean that the code has to go out directly to production without tests. The pipeline should definitely include automated tests and it can also include a deployment to a staging environment for a smoke test.

Feature flags bring advantages even without continuous deployment, but continuous deployment is a big one! High-performance teams use continuous deployment!

Use Abstractions

Often, a simple if/else in your code is good enough to implement a feature flag. The if condition checks whether the feature is enabled and, depending on the result, you go through the new code (i.e. the new feature) or the old code.

When a feature gets bigger, however, or you do a refactoring that spans many places in the code, a single if/else doesn’t cut it anymore. If you want to put these changes behind a feature flag, you would have to sprinkle if conditions all over the codebase! How ugly! And not very maintainable!

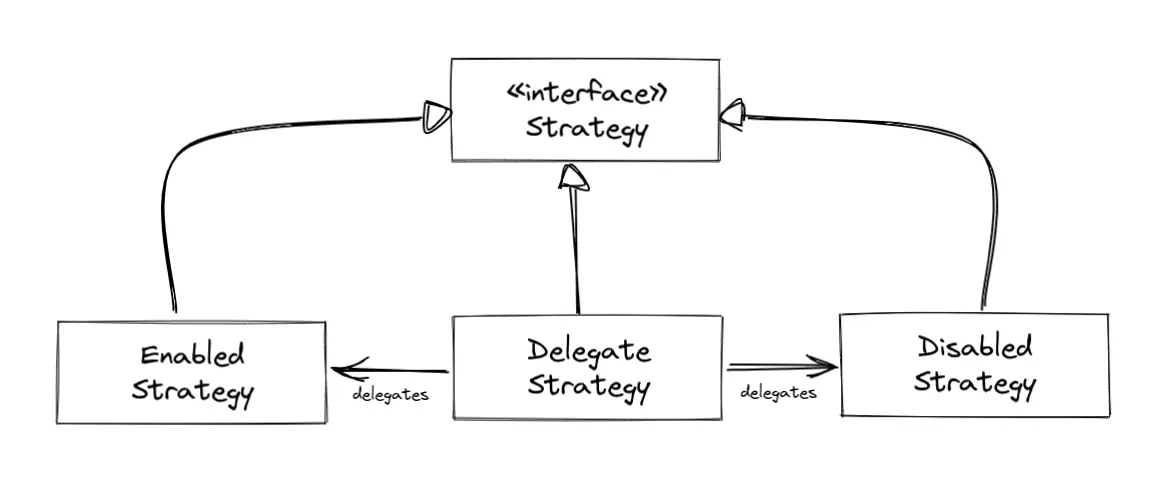

To avoid that, think about introducing an abstraction for the changes you want to make. You could use the strategy pattern, for example, with one strategy implementation for the “disabled” state of the feature flag and another implementation for the “enabled” state. You can even implement a delegate strategy that knows the other strategies and decides when to use which strategy based on the state of the feature flag:

This way, instead of sprinkling if conditions all over your code, you have the feature encapsulated cleanly within an object and can call this object’s methods instead of polluting your codebase with lots of if conditions.

This also makes the feature more evident in the code. If the feature needs updating, it’s easier to find because it’s all in one place and not distributed across the codebase.

Test in Production

Testing in production sounds scary and is often considered a no go. Without feature flags, if things were hard to test locally, for example, because of dependencies on other systems or a certain state of data in the production environment, developers would have to release a feature to production blindly and then test it. If the test failed, they would have to revert the change quickly and redeploy because it’s now failing for every user!

With feature flags “testing in production” is no longer a taboo! Instead of releasing the change to all users, we can release the change just for ourselves! Using a feature management platform like LaunchDarkly, we can enable a feature flag for a test user in the production environment and then log in as that user and test the change in the production environment. All other users are not affected by the change in any way.

If the test fails, we don’t have to revert and redeploy. Instead, we can just disable the feature again. Or we can leave it enabled because we have only enabled it for our test user anyway, so no other users have been affected at any time!

Having the opportunity to test in production doesn’t mean that this should be the standard way of testing, though. There need to be automated tests in place that run before each deployment to make sure that we haven’t introduced regressions. Testing in production is an option we have in our toolbox, however, if we use feature flags.

Rollout Progressively

Using feature flags, we not only have the opportunity to enable a feature just for us to test in production, but we can also roll the feature out to more and more users over time.

Instead of enabling a feature for everyone after we have successfully tested it, we can enable it for a percentage of all users, for example. On day one, we may only enable the feature for 5% of users. If any of those users report a problem, we can disable the feature again and investigate. If all is good, we may enable the feature for 25% of the users the next day, and 100% the day after.

Another way of rolling out progressively is to define user cohorts. Some users are very interested in new features, even if they might be a bit buggy, yet. These users we can group into an “early adopter” cohort. Then, we can release all new features to this cohort first, asking for feedback, before we roll it out to everyone else.

Rolling out features to a percentage of users or a user cohort requires a feature management platform like LaunchDarkly that supports percentage rollout and user cohorts.

Monitor the Rollout

A progressive rollout only makes sense if we check how the rollout is going. Is the feature working as expected for the first cohort of users? Do they report any issues? Can we see any errors popping up in our logs or metrics?

When adding a feature flag to the code, we should think about how we can monitor the health of the feature once we enable the feature flag. Can we add some logging that tells us the feature is working as expected? Can we emit some monitoring metrics that will appear on our dashboards that will tell us if something goes wrong?

Then, once we’re rolling out the feature (i.e. enabling the feature flag for a cohort of users), we can monitor these logs and metrics to decide whether the feature is working as expected. This allows us to make educated decisions about whether to continue rolling out to the next cohort or disabling the feature again to fix things.

Test your Feature Flags

Adding a feature flag to a codebase is like adding any other code: things can go wrong. A common mistake when adding a feature flag is to accidentally invert the if condition, i.e. execute some code when the feature flag is disabled when you actually wanted to execute the code when the feature flag is enabled.

Since we rely on feature flags to roll out even unfinished features, we must get the feature flags right. That means - same as for other code - feature flagged code should be covered by automated tests.

Your tests should cover all values a feature flag can have. Most commonly, a feature flag only has the values true and false (i.e. enabled and disabled), so there should be two tests. But a feature flag also may have a string value, for example. In this case, make sure that you have tests for valid strings as well as invalid strings. What is the code doing if the feature flag has an invalid value? What is the code doing if the feature flag has no value at all (for example when your feature management platform has an outage)? Those are all scenarios that should be covered by tests.

Cache Feature Flag State in Loops

When using a feature management service as the source of truth for the state of your feature flags, your code has to somehow get the state of a feature flag from that service. That means the code might have to make an expensive remote call to get the feature flag state.

Imagine now that you are doing some batch processing in a loop and for each iteration, you evaluate a feature flag to do a certain processing step or not. That means one potential remote call to the feature management service per iteration of that loop! Even the most performance-optimized code will slow down to a crawl!

When you need a feature flag in a loop, consider storing the value of the feature flag in a variable before entering the loop. Then you can use this variable in the loop to avoid a remote call per iteration. Or use some other mechanism to cache the value of the feature flag so you don’t have to do a remote call every time.

Depending on the feature you’re implementing, this may not be acceptable, though. Sometimes you want to be able to control the value of the feature flag in real time. Imagine you realize something is going wrong after the loop has started and you want to disable the feature flag for the rest of iterations. If you have cached the feature flag value, you can’t disable it on the fly and the rest of iterations will run with the old feature flag value.

Modern feature management services like LaunchDarkly provide clients that are smart enough not to make a remote call for every feature flag evaluation. Instead, the server pushes the feature flag values to the client every time they change. Anyway, it pays out to understand the capabilities of the feature flag client before using it in a loop.

Name Feature Flags Consistently

Naming is hard. That’s true for programming in general and feature flags in particular.

Same as for the rest of our code, feature flag code should be easily understandable. If a feature flag is misinterpreted it might mean that a feature goes out to users that shouldn’t see the feature, yet. That means that feature flags should be named in a way that tells us very clearly what the feature flag is doing.

Try to find a naming pattern for your feature flags that makes it easy to recognize their meaning.

A simple naming pattern is “XYZEnabled”. It’s clear that when this feature flag’s value is true, the feature is enabled and otherwise, it’s disabled.

Try to avoid negated feature flag names like “XYZDisabled”, because that makes for awkward double-negation if conditions in your code like if !(XYZDisabled) {...}.

Don’t Nest Feature Flags

You probably have seen code before that is deeply nested like this:

if(FooEnabled) {

if(BarEnabled) {

...

} else {

if(BazEnabled) {

...

} else {

...

}

}

} else {

...

}

This code has a high cyclomatic complexity, meaning there are a lot of different branches the code can go through. This makes the code hard to understand and reason about.

The same is true for feature flags. Every evaluation of a feature flag in your code opens up another branch that may or may not be executed depending on the value of the feature flag.

It’s bad enough that feature flags increase the cyclomatic complexity of our code so we shouldn’t make it worse by unnecessarily nesting feature flags.

In the above code, the feature Baz only has an effect if the features Foo and Bar are also enabled. There may be valid reasons for this, but this is very hard to understand. Every time you want to enable or disable the Baz feature for a cohort of users, you have to make sure that the other two features are also enabled or disabled for the same cohort.

At some point, you will make a mistake and not get the results you expect!

Clean Up Your Feature Flags

As we can see in the code above, feature flags add code to your codebase that is not really nice to read (even if you don’t nest feature flags). Once a feature has been rolled out to all users, you should remove the code from the codebase, because you no longer need to check whether the feature is enabled or not - it should be enabled for everyone and that means you don’t need an if condition anymore.

Also, bad things can happen if you keep the feature flag code in your codebase. Someone might stumble over the feature flag and accidentally disable it for a cohort of users or even all of them.

Sometimes, however, you might want to keep a feature flag around to act as a kill switch to quickly disable a feature should it cause problems.

Weigh the value of a kill switch against the toil of keeping the code around when you decide whether to keep a feature flag in the code or not.

Use a Feature Management Platform

While feature flags can be implemented with a simple if/else branch for simple use cases, they are only really powerful if you are using a feature management platform like LaunchDarkly.

These platforms let you define user cohorts and roll out features to one cohort after another with the flick of a switch in a browser-based UI.

They also allow you to monitor when feature flags have been evaluated to give you insights about the usage of your features, among a lot of other things.

If you’re starting with feature flags today, start with a feature management platform.