Believing Roy Fielding, who first coined the REST acronym, you may call your API a REST API only if you make use of hypertext. But what is hypermedia? This article explains what hypermedia means for creating an API, what benefits it brings and which drawbacks you might encounter when using it.

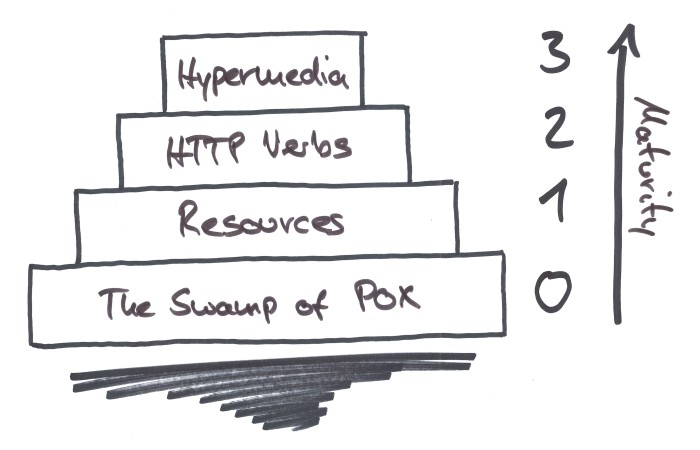

The REST Maturity Model

Before starting with Hypermedia, let’s have a look at the REST Maturity Model conceived by Leonard Richardson:

At the bottom of the maturity pyramid we find the “Swamp of POX (Plain old XML)”. This means sending XML fragments back and forth that contain a command for executing one of several procedures as well as some payload data to a single URL. Basically, this is RPC (Remote Procedure Call) like it’s done in typical SOAP webservice.

Level 1 breaks up the “single URL” part by providing separate URLs for separate “things”. These “things” are called resources in REST-lingo. Separating concerns into different URLs is just a matter of following the software engineering principle of, well, Separation of concerns.

Level 2 then builds on top of these resource URLs and provides meaningful, standardized “operations” on those resources.

These operations are the HTTP Verbs, most commonly GET, POST, PUT and DELETE. This way, we have a set

of verbs we can combine with a resource URL to modify the resource. Common practice is to use

GETto load a resourcePOSTto create a new resourcePUTto modify an existing resource andDELETEto remove a resource.

Level 3 adds hypermedia to the mix, consisting of hyperlinks between resources, with each link representing a relation between the connected resources. The concepts behind level 3 are a little more academic than the other levels, and are a little harder to grasp. Read on to follow my attempt to grasp them.

Hypermedia

I will use the term “Hypermedia” as a shorthand for “Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State” (HATEOAS), which is one of the ugliest acronyms I’ve ever seen. Basically, it means that a REST API provides hyperlinks with each response that link to other related resources.

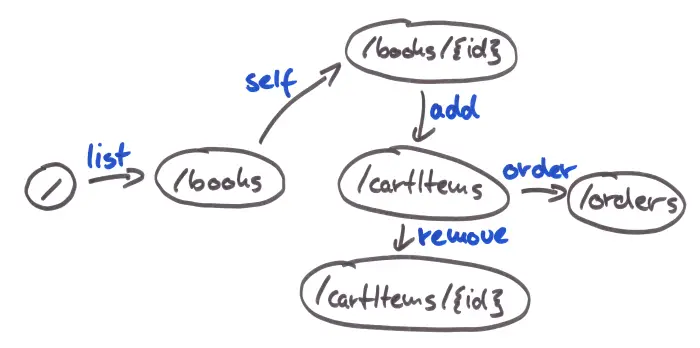

Let’s try this concept on a simple book store example:

In the diagram above, each node is a URL within our API and each edge is a link relating one URL with another.

Hypermedia means that those links will be returned together with the actual response payload. Let’s walk through the diagram.

Calling the root of the API (/), we will get a response that has no actual payload but a single link to /books

with the relation list. This response might look like this when using the HAL

format:

{

"_links": {

"list": {

"href": "/books"

}

}

}

Following this link, we can call /books to get a list of books, which might look like this:

{

"_embedded": {

"booksList": [

{

"title": "Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy",

"author": "Douglas Adams",

"_links": {

"self": {

"href": "/books/42"

}

}

},

// more books ...

]

}

}

The self link on each book points us to the corresponding book resource.

The book resource response then might contain a relation add linking to /cartItems, allowing us to add

the book to the shopping cart.

All in all, just by following the links in the API’s responses we can browse books, add them to our shopping cart or remove them from it, and finally order the contents of our shopping cart.

Why Hypermedia Makes Sense

Having understood the basics of hypermedia in REST APIs, let’s discuss the pros.

The main argument for going the extra mile to level 3 and create a hypermedia-driven API is that it helps to decouple the consumer from the provider. This brings some advantages …

Refactoring Resource URLs

The consumer does not need to know all the URLs to the API’s endpoints, because it can navigate the API over the hyperlinks provided in the responses. This gives the provider the freedom to refactor the endpoint URLs at will without consulting the consumers at all.

Changing Client Behavior without Changing Code

Another decoupling feature is that the consumer can change its behavior depending on which links are provided by the

server. In the book store example above, the server may decide not to include the order link in its responses

until the shopping cart has reached a minimum value. The client knows that and only displays a checkout button

once it gets the order link from the server.

Explorable API

Obviously, by following the hyperlinks, our REST API is explorable by a client. However, it’s also explorable by a human. A developer that knows the root URL can simply follow the links to get a feel for the API.

Using a tool like HAL Browser, the API can even be browsed and experimented with comfortably.

Why You Might Not Want to Use Hypermedia

While decoupling client and server is a very worthwhile goal, when implementing a hypermedia API you may stumble over a few things.

Client Must Evaluate Hyperlinks

First of all, the decoupling aspect of the hyperlinks gets lost if the client chooses not to evaluate the hyperlinks but instead uses hard-coded URLs to access the API.

In this case, all the effort that has gone into crafting a semantically powerful hypermedia API was in vain, since the client does not take advantage of it and we loose all decoupling advantages.

In a public-facing API, there will most probably be clients that will use hard-coded URLs and NOT evaluate the hyperlinks. So, as the API provider, we lose the advantage of hyperlinks because we still cannot refactor URLs independently without irritating our users.

Client Must Understand Relations

If the client chooses to evaluate the hyperlinks, it obviously needs to understand the relations

to make sense of them. In the example above, the client needs to know what the remove relation means

in order to present the user with a UI that lets him remove an item from the shopping cart.

Having to understand the relations in itself is a good thing, but building a client that acts on those relations alone is harder than building a client that is more tightly coupled to the server, which is probably a main reason that most APIs don’t go to level 3.

Server Must Describe Application Completely with Relations

Similarly, describing the whole application state with relations and hyperlinks is a burden on the server side - at least initially. Designing and Building a hypermedia API is plain more effort than building a level 2 API.

To be fair, once the API is stable it’s probably less effort to maintain a hypermedia API than a level 2 API, thanks to the decoupling features. But building a hypermedia API is a long-term invest few managers are willing to make.

No Standard Hypermedia Representation

Another reason why hypermedia is not yet widely adopted is the lack of a standard format. There’s RFC 5988, specifying a syntax for links contained in HTTP headers. Then there’s HAL, JSON Hyper-Schema and other formats, each specifying a syntax for links within JSON resources.

Each of these formats has a different view on which information should be included in hyperlinks. This raises uncertainty amongst developers and makes development of general-purpose hypermedia frameworks harder for both the client side and the server side.

Client Must Still Have Domain Knowledge

Hypermedia is not a silver bullet for decoupling client from server. The client still needs to know the structure of the resources it loads from the server and posts back to the server. This structure contains a large part of the domain knowledge, so the decoupling is far from complete.

Bigger Response Payload

As you can see in the JSON examples above, hypermedia APIs tend to have bigger response payloads than a level 2 API. The links and relations need to be transferred from server to client somehow, after all. Thus, an API implemented with hypermedia will probably need more bandwidth than the same API without.

How Should I Implement My New Shiny API?

In my opinion, there’s no golden way of creating a REST API.

If, in your project, the advantages of hypermedia outweigh the disadvantages - mainly effort in careful design and implementation - then go for hypermedia and be one of the few who can claim to have built a glorious level 3 REST API :).

If you’re not sure, go for level 2. Especially if the client is not under your control, this may be the wiser choice and save some implementation effort. However, be aware that you may not call your API a “REST API” then … .