Streams, introduced in Java 8, use functional-style operations to process data declaratively. The elements of streams are consumed from data sources such as collections, arrays, or I/O resources like files.

In this article, we’ll explore the various possibilities of using streams to make life easier when it comes to the handling of files. We assume that you have a basic knowledge of Java 8 streams. If you are new to streams, you may want to check out this guide.

Introduction

In the Stream API, there are operations to filter, map, and reduce data in any order without you having to write extra code. Here is a classic example:

List<String> cities = Arrays.asList(

"London",

"Sydney",

"Colombo",

"Cairo",

"Beijing");

cities.stream()

.filter(a -> a.startsWith("C"))

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.sorted()

.forEach(System.out::println);

Here we filter a list of countries starting with the letter “C”, convert to uppercase and sort it before printing the result to the console.

The output is as below:

CAIRO

COLOMBO

As the returned streams are lazily loaded, the elements are not read until they are used (which happens when the terminal operation is called on the stream).

Wouldn’t it be great to apply these SQL-like processing capabilities to files as well? How do we get streams from files? Can we walk through directories and locate matching files using streams? Let us get the answers to these questions.

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.Getting Started

Converting files to streams helps us to easily perform many useful operations like

- counting words in the lines,

- filtering files based on conditions,

- removing duplicates from the data retrieved,

- and others.

First, let us see how we can obtain streams from files.

Building Streams from Files

We can get a stream from the contents of a file line by line by calling the lines() method of the Files class.

Consider a file bookIndex.txt with the following contents.

Pride and Prejudice- pride-and-prejudice.pdf

Anne of Avonlea - anne-of-avonlea.pdf

Anne of Green Gables - anne-of-green-gables.pdf

Matilda - Matilda.pdf

Why Icebergs Float - Why-Icebergs-Float.pdf

Using Files.lines()

Let us take a look an example where we read the contents of the above file:

Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"));

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

As shown in the example above, the lines() method takes the Path representing the file as an argument. This method does not read all lines into a List, but instead populates lazily as the stream is consumed and this allows efficient use of memory.

The output will be the contents of the file itself.

Using BufferedReader.lines()

The same results can be achieved by invoking the lines() method on BufferedReader also. Here is an example:

BufferedReader br = Files.newBufferedReader(Paths.get("bookIndex.txt"));

Stream<String> lines = br.lines();

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

As streams are lazy-loaded in the above cases (i.e. they generate elements upon request instead of storing them all in memory), reading and processing files will be efficient in terms of memory used.

Using Files.readAllLines()

The Files.readAllLines() method can also be used to read a file into a List of String objects. It is possible to create a stream from this collection, by invoking the stream() method on it:

List<String> strList = Files

.readAllLines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"));

Stream<String> lines = strList.stream();

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

However, this method loads the entire contents of the file in one go and hence is not memory efficient like the Files.lines() method.

Importance of try-with-resources

The try-with-resources syntax provides an exception handling mechanism that allows us to declare resources to be used within a Java try-with-resources block.

When the execution leaves the try-with-resources block, the used resources are automatically closed in the correct order (whether the method successfully completes or any exceptions are thrown).

We can use try-with-resources to close any resource that implements either AutoCloseable or Closeable.

Streams are AutoCloseable implementations and need to be closed if they are backed by files.

Let us now rewrite the code examples from above using try-with-resources:

try (Stream<String> lines = Files

.lines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"))) {

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

}

try (Stream<String> lines =

(Files.newBufferedReader(Paths.get("bookIndex.txt"))

.lines())) {

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

}

The streams will now be automatically closed when the try block is exited.

Using Parallel Streams

By default, streams are serial, meaning that each step of a process is executed one after the other sequentially.

Streams can be easily parallelized, however. This means that a source stream can be split into multiple sub-streams executing in parallel.

Each substream is processed independently in a separate thread and finally merged to produce the final result.

The parallel() method can be invoked on any stream to get a parallel stream.

Using Stream.parallel()

Let us see a simple example to understand how parallel streams work:

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"))

.parallel()) {

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

}

Here is the output:

Anne of Green Gables - anne-of-green-gables.pdf

Why Icebergs Float - Why-Icebergs-Float.pdf

Pride and Prejudice- pride-and-prejudice.pdf

Matilda - Matilda.pdf

Anne of Avonlea - anne-of-avonlea.pdf

You can see that the stream elements are printed in random order. This is because the order of the elements is not maintained when forEach() is executed in the case of parallel streams.

Parallel streams may perform better only if there is a large set of data to process.

In other cases, the overhead might be more than that for serial streams. Hence, it is advisable to go for proper performance benchmarking before considering parallel streams.

Reading UTF-Encoded Files

What if you need to read UTF-encoded files?

All the methods we saw until now have overloaded versions that take a specified charset also as an argument.

Consider a file named input.txt with Japanese characters:

akarui _ あかるい _ bright

Let us see how we can read from this UTF-encoded file:

try (Stream<String> lines =

Files.lines(Path.of("input.txt"), StandardCharsets.UTF_8)) {

lines.forEach(System.out::println);

}

In the above case, you can see that we pass StandardCharsets.UTF_8 as an argument to the Files.lines() method which allows us to read the UTF-encoded file.

Bytes from the file are decoded into characters using the specified charset.

We could also have used the overloaded version of BufferedReader for reading the file:

BufferedReader reader =

Files.newBufferedReader(path, StandardCharsets.UTF_8);

Using Streams to Process Files

Streams support functional programming operations such as filter, map, find, etc. which we can chain to form a pipeline to produce the necessary results.

Also, the Stream API provides ways to do standard file IO tasks such as listing files/folders, traversing the file tree, and finding files.

Let’s now look into a few of such cases to demonstrate how streams make file processing simple. We shall use the same file bookIndex.txt that we saw in the first examples.

Filtering by Data

Let us look at an example to understand how the stream obtained by reading this file can be filtered to retain only some of their elements by specifying conditions:

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"))) {

long i = lines.filter(line -> line.startsWith("A"))

.count();

System.out.println("The count of lines starting with 'A' is " + i);

}

In this example, only the lines starting with “A” are filtered out by calling the filter() method and the number of such lines counted using the count() method.

The output is as below:

The count of lines starting with 'A' is 2

Splitting Words

So what if we want to split the lines from this file into words and eliminate duplicates?

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Path.of("bookIndex.txt"))) {

Stream<String> words = lines

.flatMap(line -> Stream.of(line.split("\\W+")));

Set<String> wordSet = words.collect(Collectors.toSet());

System.out.println(wordSet);

}

As shown in the example above, each line from the file can be split into words by invoking the split() method.

Then we can combine all the individual streams of words into one single stream by invoking the flatMap() method.

By collecting the resulting stream into a Set, duplicates can be eliminated.

The output is as below:

[green, anne, Why, Prejudice, Float, pdf, Pride,

Avonlea, and, pride, of, prejudice, Matilda,

gables, Anne, avonlea, Icebergs, Green, Gables]

Reading From CSV Files Into Java Objects

If we need to load data from a CSV file into a list of POJOs, how can we achieve it with minimum code?

Again, streams come to the rescue.

We can write a simple regex-based CSV parser by reading line by line from the file, splitting each line based on the comma separator, and then mapping the data into the POJO.

For example, assume that we want to read from the CSV file cakes.csv:

#Cakes

1, Pound Cake,100

2, Red Velvet Cake,500

3, Carrot Cake,300

4, Sponge Cake,400

5, Chiffon Cake,600

We have a class Cake as defined below:

public class Cake {

private int id;

private String name;

private int price;

...

// constructor and accessors omitted

}

So how do we populate objects of class Cake using data from the cakes.csv file? Here is an example:

Pattern pattern = Pattern.compile(",");

try (Stream<String> lines = Files.lines(Path.of(csvPath))) {

List<Cake> cakes = lines.skip(1).map(line -> {

String[] arr = pattern.split(line);

return new Cake(

Integer.parseInt(arr[0]),

arr[1],

Integer.parseInt(arr[2]));

}).collect(Collectors.toList());

cakes.forEach(System.out::println);

}

In the above example, we follow these steps:

- Read the lines one by one using

Files.lines()method to get a stream. - Skip the first line by calling the

skip()method on the stream as it is the file header. - Call the

map()method for each line in the file where each line is split based on comma and the data obtained used to createCakeobjects. - Use the

Collectors.toList()method to collect all theCakeobjects into aList.

The output is as follows:

Cake [id=1, name= Pound Cake, price=100]

Cake [id=2, name= Red Velvet Cake, price=500]

Cake [id=3, name= Carrot Cake, price=300]

Cake [id=4, name= Sponge Cake, price=400]

Cake [id=5, name= Chiffon Cake, price=600]

Browsing, Walking, and Searching for Files

java.nio.file.Files has many useful methods that return lazy streams for listing folder contents, navigating file trees, finding files, getting JAR file entries etc.

These can then be filtered, mapped, reduced, and so on using Java 8 Stream API. Let us explore this in more detail.

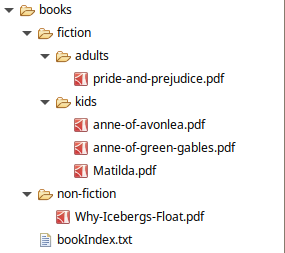

Consider the folder structure below based on which we shall be looking at some examples below.

Listing Directory Contents

What if we just want to list the contents of a directory? A simple way to do this is by invoking the Files.list() method, which returns a stream of Path objects representing the files inside the directory passed as the argument.

Listing Directories

Let us look at some sample code to list directories:

try (Stream<Path> paths = Files.list(Path.of(folderPath))) {

paths.filter(Files::isDirectory)

.forEach(System.out::println);

}

```text

In the example, we use `Files.list()` and apply a filter to the resulting stream of paths to get only the directories printed out to the console.

The output might look like this:

```text

src/main/resources/books/non-fiction

src/main/resources/books/fiction

Listing Regular Files

So what if we need to list only regular files and not directories? Let us look at an example:

try (Stream<Path> paths = Files.list(Path.of(folderPath))) {

paths.filter(Files::isRegularFile)

.forEach(System.out::println);

}

As shown in the above example, we can use the Files::IsRegularFile operation to list only the regular files.

The output is as below:

src/main/resources/books/bookIndex.txt

Walking Recursively

The Files.list() method we saw above is non-recursive, meaning it does not traverse the subdirectories. What if we need to visit the subdirectories too?

The Files.walk() method returns a stream of Path elements by recursively walking the file tree rooted at a given directory.

Let’s look at an example to understand more:

try (Stream<Path> stream = Files.walk(Path.of(folderPath))) {

stream.filter(Files::isRegularFile)

.forEach(System.out::println);

}

In the above example, we filter the stream returned by the Files.walk() method to return only regular files (subfolders are excluded).

The output is as below:

src/main/resources/books/non-fiction/Why-Icebergs-Float.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/anne-of-green-gables.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/anne-of-avonlea.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/Matilda.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/adults/pride-and-prejudice.pdf

src/main/resources/books/bookIndex.txt

Finding Files

In the previous example, we saw how we can filter stream obtained from the Files.walk() method. There is a more efficient way of doing this by using the Files.find() method.

Files.find() evaluates a BiPredicate (a matcher function) for each file encountered while walking the file tree. The corresponding Path object is included in the returned stream if the BiPredicate returns true.

Let us look at an example to see how we can use the find() method to find all PDF files anywhere within the given depth of the root folder:

int depth = Integer.MAX_VALUE;

try (Stream<Path> paths = Files.find(

Path.of(folderPath),

depth,

(path, attr) -> {

return attr.isRegularFile() && path.toString().endsWith(".pdf");

})) {

paths.forEach(System.out::println);

}

In the above example, the find() method returns a stream with all the regular files having the .pdf extension.

The depth parameter is the maximum number of levels of directories to visit. A value of 0 means that only the starting file is visited, unless denied by the security manager. A value of MAX_VALUE may be used to indicate that all levels should be visited.

Output is:

src/main/resources/books/non-fiction/Why-Icebergs-Float.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/anne-of-green-gables.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/anne-of-avonlea.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/kids/Matilda.pdf

src/main/resources/books/fiction/adults/pride-and-prejudice.pdf

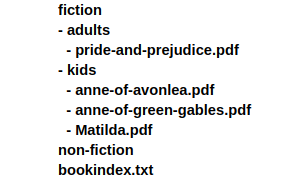

Streaming JAR Files

We can also use streams to read the contents of JAR files.

The JarFile.stream() method returns an ordered Stream over the ZIP file entries. Entries appear in the stream in the order they appear in the central directory of the ZIP file.

Consider a JAR file with the following structure.

So how do we iterate through the entries of the JAR file? Here is an example which demonstrates this:

try (JarFile jFile = new JarFile(jarFile)) {

jFile.stream().forEach(file -> System.out.println(file));

}

The contents of the JAR file will be iterated and displayed as shown below:

bookIndex.txt

fiction/

fiction/adults/

fiction/adults/pride-and-prejudice.pdf

fiction/kids/

fiction/kids/Matilda.pdf

fiction/kids/anne-of-avonlea.pdf

fiction/kids/anne-of-green-gables.pdf

non-fiction/

non-fiction/Why-Icebergs-Float.pdf

What if we need to look for specific entries within a JAR file?

Once we get the stream from the JAR file, we can always perform a filtering operation to get the matching JarEntry objects:

try (JarFile jFile = new JarFile(jarFile)) {

Optional<JarEntry> searchResult = jFile.stream()

.filter(file -> file.getName()

.contains("Matilda"))

.findAny();

System.out.println(searchResult.get());

}

In the above example, we are looking for filenames containing the word “Matilda”. So the output will be as follows.

fiction/kids/Matilda.pdf

Conclusion

In this article, we discussed how to generate Java 8 streams from files using the API from the java.nio.file.Files class .

When we manage data in files, processing them becomes a lot easier with streams. A low memory footprint due to lazy loading of streams is another added advantage.

We saw that using parallel streams is an efficient approach for processing files, however we need to avoid any operations that require state or order to be maintained.

To prevent resource leaks, it is important to use the try-with-resources construct, thus ensuring that the streams are automatically closed.

We also explored the rich set of APIs offered by the Files class in manipulating files and directories.

The example code used in this article is available on GitHub.