A microservice architecture is all about communication. How should services communicate in any given business scenario? Should they call each other synchronously? Or should they communicate via asynchronous messaging? As always, this is not a black-or-white decision. This article discusses some prominent communication patterns.

Synchronous Calls

The probably easiest communication pattern to implement is simply calling another service synchronously, usually via REST.

Service 1 calls Service 2 and waits until Service 2 is done processing the request and returns a response. Service 1 can then process Service 2’s response in the same transaction that triggered the communication.

This pattern is easy to grasp since we are doing it all the time in any web application out there. It’s also well supported by technology. Netflix have open sourced support for synchronous communication in form of the Feign and Hystrix libraries.

Let’s discuss some pros and cons.

Timeouts

What if Service 2 needs very long to process the Service 1’s request and Service 1 is tired of waiting? Service 1 will then probably have some sort of timeout exception and roll back the current transaction. However, Service 2 doesn’t know that Service 1 rolled back the transaction and might process the request after all, perhaps resulting in inconsistent data between the two services.

Strong Coupling

Naturally, synchronous communication creates a strong coupling between the services. Service 1 cannot work without Service 2 being available. To mitigate this, we have to work around communication failures by implementing retry and / or fallback mechanisms. Luckily, we have Hystrix, enabling us to do exactly this. However, retries and fallbacks only go so far and might not cover all business requirements.

Easy to Implement

Hey, it’s synchronous communication! We’ve all done it before. And thus we can do it again easily. Let’s just get the latest version of our favorite HTTP client library and implement it. It’s easy as pie (as long as we don’t have to think about retries and fallbacks, that is).

Simple Messaging

Asynchronous messaging is the next option we take a look at.

Service 1 fires a message to a message broker and forgets about it. Service 2 subscribes to a topic is fed with all messages belonging to that topic. The services don’t need to know each other at all, they just need to know that there are messages of a certain type with a certain payload.

Let’s discuss messaging.

Automatic Retry

Depending on the message broker, we get a retry mechanism for free. If Service 2 is currently not available, the message broker will try to deliver the message again until Service 2 finally gets it. “Guaranteed Delivery” is the magic keyword.

Loose Coupling

Along the same lines, messaging makes the services loosely coupled since Service 2 doesn’t need to be available at the time Service 1 sends the message.

Message Broker must not fail

Using a message broker, we just introduced a piece of central infrastructure that is needed by all services that want to communicate asynchronously. If it fails, hell will break loose (and all services cease functioning).

Pipeline contains Schema

It’s worthy to note that messages (even if they are JSON) define a certain schema within the message broker. If the format of a message changes (and the change is not backwards compatible), then all messages of that type must have been processed by all subscribers before the new service versions can be deployed.

This contradicts independent deployments, one of the main goals of microservices. This can be mitigated by only allowing backward compatible changes to message formats (which may not always be possible).

Two-Phase Commit

Another caveat is that we usually send messages as part of our business logic and the business logic is usually bound to a database transaction. If the database transaction rolls back, a message may have already been sent to the message broker.

This can be addressed by implementing two-phase commit between the database transaction and the message broker. However, two-phase commit may not be supported by the database or the message broker and even if it is, it’s often a pain to get working and even more so to test reliably.

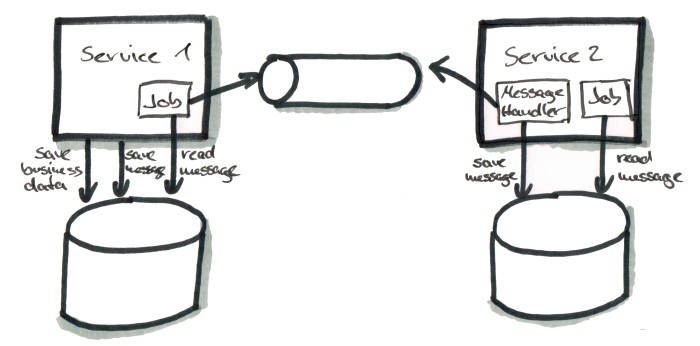

Transactional Messaging

We can modify the simple messaging scenario from above for some benefits.

Instead of sending a message directly to the message broker, we now store it in the service’s database first. Same on the receiving side: here the message gets stored into the receiver service’s database before it is being processed.

No Need for Two-Phase Commit

Since we’re writing the message to a local database table we can use the same transaction that our business logic uses. If the business logic fails, the transaction is rolled back and so is our message. We cannot accidentally send messages any more when our local transaction has been rolled back.

Message Broker may Fail

Since we’re storing our messages in the local database on the sending and the receiving side, the message broker may fail anytime and the system will magically heal itself once it’s back online. We can just send the messages again from our message database table.

Complex Setup

The above perks aren’t for free, of course. The setup is quite complex, since we need to store the messages in the database of the sending and reveiving services. Also, we need to implement jobs on both sides that poll the database, looking for unprocessed messages and then process them by

- sending them to the message broker (on the sending side) or

- calling the business logic that processes the message (on the receiving side)

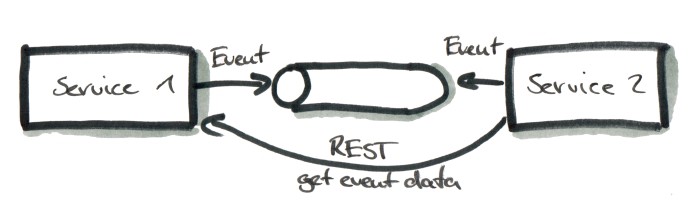

Zero-Payload Events

The last scenario is similar to the messaging example, but we’re not sending whole messages (i.e. big JSON objects) but instead only a pointer to the payload.

In this case, the message is more like an event. It signals that something happened, for example that “the order with ID 4711 has been shipped”. Thus, the message itself only contains the type of the event (“orderShipped”) and the ID of the order (4711). If Service 2 is interested in the “orderShipped” event, it can then synchronously call Service 1 and ask for the order data.

Dumb Pipe

This scenario takes most of the message structure from the message broker, making it a dumber pipe (as is desirable in a microservice architecture). We don’t have to think that much on maintaining backwards compatibility within the message structure anymore, since we have almost no message structure. Note, however, that the little message structure we have left should still change in a backwards compatible fashion between two releases.

Combinable with Transactional Messaging

Combining the zero-payload approach with the transactional messaging approach from above, we gain all the benefits of not needing two-phase commit and gaining a retry-mechanism even when the message broker fails. This adds even more complexity to the solution though, since we now also have to implement synchronous calls between the services to get the event payloads.

When to use which Approach?

As mentioned in the introduction, there is no black-and-white decision between the communication patterns described above. However, let’s try to find some indications on when we might use which approach.

We might want to use Synchronous Calls if:

- we want to query some data, because a query is not changing any state so we don’t have to worry about distributed transactions and data consistency across service boundaries

- the call is allowed to fail and we don’t need a sophisticated retry mechanism

We might want to use Simple Messaging if:

- we want to send state-changing commands

- the operation must be performed eventually, even if it fails the first couple times

- we don’t care about potentially complex message structure

We might want to use Transactional Messaging if:

- we want to send state-changing commands only when the local database transaction has been successful

- two-phase commit is not an option

- we don’t trust the message broker (actually, better look for one you trust)

We might want to use Zero Payload Events if:

- we want to send state-changing commands

- we would otherwise have a very complex message structure that is hard to maintain in a backwards-compatible way