You are just beginning your programming career? Or you have dabbled a bit in programming but want to get into Java?

Then this article is for you. We’ll go from zero to building a robot arena in Java.

If you get stuck anywhere in this tutorial, know that this is totally fine. In this case, you might want to learn Java on CodeGym. They take you through detailed and story-based Java tutorials with in-browser coding exercises that are ideal for Java beginners.

Have fun building robots with Java!

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.Getting Ready to Code

Before we can start writing code, we have to set up our development environment. Don’t worry, this is not going to be complicated. The only thing we need for now is to install an IDE or “Integrated Development Environment”. An IDE is a program that we’ll use for programming.

When I’m working with Java, IntelliJ is my IDE of choice. You can use whatever IDE you’re comfortable with, but for this tutorial, I’ll settle with instructions on how to work with IntelliJ.

So, if you haven’t already, download and install the free community edition of IntelliJ for your operating system here. I’ll wait while you’re downloading it.

IntelliJ is installed and ready? Let’s get started, then!

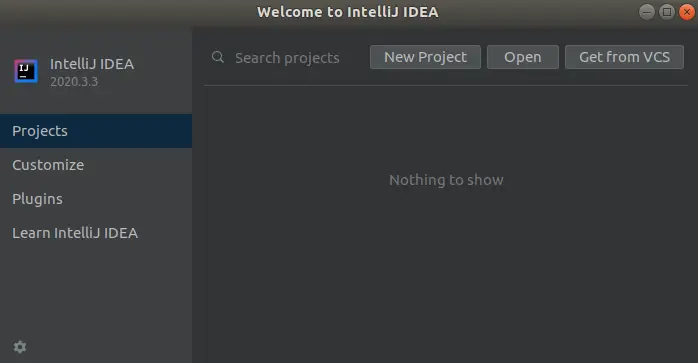

Before we get our hands dirty on code, we create a new Java project in IntelliJ. When you start IntelliJ for the first time, you should see a dialog something like this:

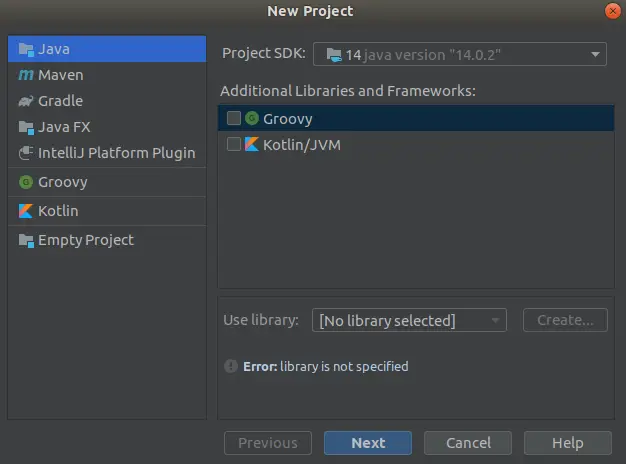

Click on “New project”, to open this dialog:

If you have a different IntelliJ project open already, you can reach the “New project” dialog through the option “File -> New -> Project”.

If the “Project SDK” drop-down box shows “No JDK”, select the option “Download JDK” in the dropdown box to install a JDK (Java Development Kit) before you continue.

Then, click “Next”, click “Next” again, enter “robot-arena” as the name of the project, and finally click “Finish”.

Congratulations, you have just created a Java project! Now, it’s time to create some code!

Level 1 - Hello World

Let’s start with the simplest possible program, the infamous “Hello World” (actually, in Java there are already quite a few concepts required to build a “Hello World” program … it’s definitely simpler in other programming languages).

The goal is to create a program that simply prints “Hello World” to a console.

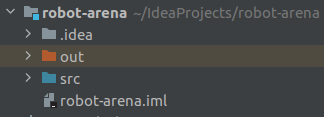

In your fresh Java project, you should see the following folder structure on the left:

There are folders named .idea and out, in which IntellJ stores some configuration and compiled Java classes … we don’t bother with them for now.

The folder we’re interested in is the src folder, which stands short for “source”, or rather “source code” or “source files”. This is where we put our Java files.

In this folder, create a new package by right-clicking on it and selecting “New -> Package”. Call the package “level1”.

Packages

In Java, source code files are organized into so-called "packages". A package is just a folder in your file system and can contain files and other packages, just like a normal file system folder.

In this tutorial, we'll create a separate package for each chapter (or "level") with all the source files we need for that chapter.

In the package level1, go ahead and create a new Java file by right-clicking on it and selecting “New -> Java Class”. Call this new class “Application”.

Copy the following code block into your new file (replacing what is already there):

package level1;

public class Application {

public static void main(String[] arguments){

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}

Java programs are organized into “classes”, where each class is usually in its own separate Java file with the same name of the class (more about classes later). You will see that IntelliJ has created a file with the name Application.java and the class within is also called Application. Each class is in a certain package, which is declared with package level1; in our case above.

Our Application class contains a method called main(). A class can declare many methods like that with names that we choose - we’ll see how later in this tutorial. A method is a unit of code in a class that we can execute. It can have input in the form of arguments and output in the form of a return value. Our main() method takes an array of Strings as input and returns a void output, which means it returns no output (check out the vocabulary at the end of this article if you want to recap what a certain term means).

A method named main() with the public and static modifiers is a special method because it’s considered the entry point into our program. When we tell Java to run our program, it will execute this main() method.

Let’s do this now. Run the program by right-clicking the Application class in the project explorer on the left side and select “Run ‘Application.main()'” from the context menu.

IntelliJ should now open up a console and run the program for us. You should see the output “Hello World” in the console.

Congratulations! You have just run your first Java program! We executed the main() method which printed out some text. Feel free to play around a bit, change the text, and run the application again to see what happens.

Let’s now explore some more concepts of the Java language in the next level.

Level 2 - Personalized Greeting

Let’s modify our example somewhat to get to know about some more Java concepts.

The goal in this level is to make the program more flexible, so it can greet the person executing the program.

First, create a new package level2, and create a new class named Application in it. Paste the following code into that class:

package level2;

public class Application {

public static void main(String[] arguments){

String name = arguments[0];

System.out.println("Hello, " + name);

}

}

Let’s inspect this code before we execute it. We added the line String name = arguments[0];, but what does it mean?

With String name, we declare a variable of type String. A variable is a placeholder that can hold a certain value, just like in a mathematical equation. In this case, this value is of the type String, which is a string of characters (you can think of it as “text”).

With String name = "Bob", we would declare a String variable that holds the value “Bob”. You can read the equals sign as “is assigned the value of”.

With String name = arguments[0], finally, we declare a String variable that holds the value of the first entry in the arguments variable. The arguments variable is passed into the main() method as an input parameter. It is of type String[], which means it’s an array of String variables, so it can contain more than one string. With arguments[0], we’re telling Java that we want to take the first String variable from the array.

Then, with System.out.println("Hello, " + name);, we print out the string “Hello, " and add the value of the name variable to it with the “+” operator.

What do you think will happen when you execute this code? Try it out and see if you’re right.

Most probably, you will get an error message like this:

Exception in thread "main" java.lang.ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException: Index 0 out of bounds for length 0

at level2.Application.main(Application.java:5)

The reason for this error is that in line 5, we’re trying to get the first value from the arguments array, but the arguments array is empty. There is no first value to get. Java doesn’t like that and tells us by throwing this exception at us.

To solve this, we need to pass at least one argument to our program, so that the arguments array will contain at least one value.

To add an argument to the program call, right-click on the Application class again, and select “Modify Run Configuration”. In the field “Program arguments”, enter your name. Then, execute the program again. The program should now greet you with your name!

Change the program argument to a different name and run the application again to see what happens.

Level 3 - Play Rock, Paper, Scissors with a Robot

Let’s add some fun by programming a robot!

In this level, we’re going to create a virtual robot that can play Rock, Paper, Scissors.

First, create a new package level3. In this package, create a Java class named Robot and copy the following content into it:

package level3;

class Robot {

String name;

Random random = new Random();

Robot(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

String rockPaperScissors() {

int randomNumber = this.random.nextInt(3);

if (randomNumber == 0) {

return "rock";

} else if (randomNumber == 1) {

return "paper";

} else {

return "scissors";

}

}

}

Let’s go through this code to understand it:

With class Robot, we declare a new class with the name “Robot”. As mentioned before, a class is a unit to organize our code. But it’s more than that. We can use a class as a “template”. In our case, the Robot class is a template for creating robots. We can use the class to create one or more robots that can play Rock, Paper, Scissors.

Learning Object-Oriented Programming

If you haven't been in contact with object-oriented programming before, the concepts of classes and objects can be a lot to take in. Don't worry if you don't understand all the concepts from reading this article alone ... it'll come with practice.

If you want to go through a more thorough, hands-on introduction to object-oriented programming with Java, you might want to take a look at CodeGym.

A class can have attributes and methods. Let’s look at the attributes and methods of our Robot class.

A robot shall have a name, so with String name; we declare an attribute with the name “name” and the type String. An attribute is just a variable that is bound to a class.

We’ll look at the other attribute with the name random later.

The Robot class then declares two methods:

- The

Robot()method is another special method. It’s a so-called “constructor” method. TheRobot()method is used to construct a new object of the class (or type)Robot. Since a robot must have a name, the constructor method expects a name as an input parameter. Withthis.name = namewe set thenameattribute of the class to the value that was passed into the constructor method. We’ll later see how that works. - The

rockPaperScissors()method is the method that allows a robot to play Rock, Paper, Scissors. It does not require any input, but it returns aStringobject. The returned String will be one of “rock”, “paper”, or “scissors”, depending on a random number. Withthis.random.nextInt(3)we use the random number generator that we have initialized in therandomattribute to create a random number between 0 and 2. Then, with an if/else construct, we return one of the strings depending on the random number.

So, now we have a robot class, but what do we do with it?

Create a new class called Application in the level3 package, and copy this code into it:

package level3;

class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Robot c3po = new Robot("C3PO");

System.out.println(c3po.rockPaperScissors());

}

}

This class has a main() method, just like in the previous levels. In this method, with Robot c3po = new Robot("C3PO"); we create an object of type Robot and store it in a variable with the name c3po. With the new keyword, we tell Java that we want to call a constructor method. In the end, this line of code calls the Robot() constructor method we have declared earlier in the Robot class. Since it requires a robot name as an input parameter, we pass the name “C3PO”.

We now have an object of type Robot and can let it play Rock, Paper, Scissors by calling the rockPaperScissors() method, which we do in the next line. We pass the result of that method into the System.out.println() method to print it out on the console.

Before you run the program, think about what will happen. Then, run it, and see if you were right!

The program should print out either “rock”, “paper”, or “scissors”. Run it a couple of times to see what happens!

Level 4 - A Robot Arena

Now we can create robot objects that play Rock, Paper, Scissors. It would be fun to let two robots fight a duel, wouldn’t it?

Let’s build an arena in which we can pit two robots against each other!

First, create a new package level4 and copy the Robot class from the previous level into this package. Then, create a new class in this package with the name Arena and copy the following code into it:

package level4;

class Arena {

Robot robot1;

Robot robot2;

Arena(Robot robot1, Robot robot2) {

this.robot1 = robot1;

this.robot2 = robot2;

}

Robot startDuel() {

String shape1 = robot1.rockPaperScissors();

String shape2 = robot2.rockPaperScissors();

System.out.println(robot1.name + ": " + shape1);

System.out.println(robot2.name + ": " + shape2);

if (shape1.equals("rock") && shape2.equals("scissors")) {

return robot1;

} else if (shape1.equals("paper") && shape2.equals("rock")) {

return robot1;

} else if (shape1.equals("scissors") && shape2.equals("paper")) {

return robot1;

} else if (shape2.equals("rock") && shape1.equals("scissors")) {

return robot2;

} else if (shape2.equals("paper") && shape1.equals("rock")) {

return robot2;

} else if (shape2.equals("scissors") && shape1.equals("paper")) {

return robot2;

} else {

// both robots chose the same shape: no winner

return null;

}

}

}

Let’s investigate the Arena class.

An arena has two attributes of type Robot: robot1, and robot2. Since an arena makes no sense without any robots, the constructor Arena() expects two robot objects as input parameters. In the constructor, we initialize the attributes with the robots passed into the constructor.

The fun part happens in the startDuel() method. This method pitches the two robots against each other in battle. It expects no input parameters, but it returns an object of type Robot. We want the method to return the robot that won the duel.

In the first two lines, we call each of the robots’ rockPaperScissors() methods to find out which shape each of the robots chose and store them in two String variables shape1 and shape2.

In the next two lines, we just print the shapes out to the console so that we can later see which robot chose which shape.

Then comes a long if/else construct that compares the shapes both robots selected. If robot 1 chose “rock” and robot 2 chose “scissors”, we return robot 1 as the winner, because rock beats scissors. This goes on for all 6 different cases. Finally, we have an unconditional else block which is only reached if both robots have chosen the same shape. In this case, there is no winner, so we return null. Null is a special value that means “no value”.

Now we have an Arena in which we can let two robots battle each other. How do we start a duel?

Let’s create a new Application class in the level4 package and copy this code into it:

package level4;

class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Robot c3po = new Robot("C3PO");

Robot r2d2 = new Robot("R2D2");

Arena arena = new Arena(c3po, r2d2);

Robot winner = arena.startDuel();

if (winner == null) {

System.out.println("Draw!");

} else {

System.out.println(winner.name + " wins!");

}

}

}

What’s happening in this code?

In the first two lines, we create two Robot objects.

In the next line, we create an Arena object, using the previously discussed constructor Arena() that expects two robots as input. We pass in the two robot objects we created earlier.

Then, we call the startDuel() method on the arena object. Since the startDuel() method returns the winner of the duel, we store the return value of the method into the winner variable of type Robot.

If the winner variable has no value (i.e. it has the value null), we don’t have a winner, so we print out “Draw!”.

If the winner variable does have a value, we print out the name of the winner.

Go through the code again and trace in your mind what happens in each line of code. Then run the application and see what happens!

Every time we run the program, it should now print out the Rock, Paper, or Scissor shapes that each of the robots has chosen and then print out the name of the winner or “Draw!” if there was no winner.

We have built a robot arena!

Level 5 - Cleaning Up the Arena

The robot arena we’ve built is pretty cool already. But the code is a bit unwieldy in some places.

Let’s clean up the code to professional-grade quality! We’ll introduce some more Java concepts on the way.

We’re going to fix three main issues with the code:

- The

rockPaperScissors()method in theRobotclass returns aString. We could accidentally introduce an error here by returning an invalid string like “Duck”. - The big if/else construct in the

Arenaclass is repetitive and error-prone: we could easily introduce an error through copy & paste here. - The

startDuel()method in theArenaclass returnsnullif there was no winner. We might expect the method to always return a winner and forget to handle the case when it returnsnull.

Before we start, create a new package level5, and copy all the classes from level4 into it.

To make the code a bit safer, we’ll first introduce a new class Shape. Create this class and copy the following code into it:

package level5;

enum Shape {

ROCK("rock", "scissors"),

PAPER("paper", "rock"),

SCISSORS("scissors", "paper");

String name;

String beats;

Shape(String name, String beats) {

this.name = name;

this.beats = beats;

}

boolean beats(Shape otherShape) {

return otherShape.name.equals(this.beats);

}

}

The Shape class is a special type of class: an “enum”. This means it’s an enumeration of possible values. In our case, an enumeration of valid shapes in the Rock, Paper, Scissors game.

The class declares three valid shapes: ROCK, PAPER, and SCISSORS. Each of the declarations passes two parameters into the constructor:

- the name of the shape, and

- the name of the shape it beats.

The constructor Shape() takes these parameters and stores them in class attributes as we have seen in the other classes earlier.

We additionally create a method beats() that is supposed to decide whether the shape beats another shape. It expects another shape as an input parameter and returns true if that shape is the shape that this shape beats.

With the Shape enum in place, we can now change the method rockPaperScissors() in the Robot class to return a Shape instead of a string:

class Robot {

...

Shape rockPaperScissors() {

int randomNumber = random.nextInt(3);

return Shape.values()[randomNumber];

}

}

The method now returns Shape object. We have also removed the if/else construct and replaced it with Shape.values()[randomNumber] to the same effect. Shape.values() returns an array containing all three shapes. From this array we just pick the element with the random index.

With this new Robot class, we can go ahead and clean up the Arena class:

class Arena {

...

Optional<Robot> startDuel() {

Shape shape1 = robot1.rockPaperScissors();

Shape shape2 = robot2.rockPaperScissors();

System.out.println(robot1.name + ": " + shape1.name);

System.out.println(robot2.name + ": " + shape2.name);

if (shape1.beats(shape2)) {

return Optional.of(robot1);

} else if (shape2.beats(shape1)) {

return Optional.of(robot2);

} else {

return Optional.empty();

}

}

}

We changed the type of the shape variables from String to Shape, since the robots now return Shapes.

Then, we have simplified the if/else construct considerably by taking advantage of the beats() method we have introduced in the Shape enum. If the shape of robot 1 beats the shape of robot 2, we return robot 1 as the winner. If the shape of robot 2 beats the shape of robot 1, we return robot 2 as the winner. If no shape won, we have a draw, so we return no winner.

You might notice that the startDuel() method now returns an object of type Optional<Robot>. This signifies that the return value can be a robot or it can be empty. Returning an Optional is preferable to returning a null object as we did before because it makes it clear to the caller of the method that the return value may be empty.

To accommodate the new type of the return value, we have changed the return statements to return either a robot with Optional.of(robot) or an empty value with Optional.empty().

Finally, we have to adapt our Application class to the new Optional return value:

class Application {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Robot c3po = new Robot("C3PO");

Robot r2d2 = new Robot("R2D2");

Arena arena = new Arena(c3po, r2d2);

Optional<Robot> winner = arena.startDuel();

if (winner.isEmpty()) {

System.out.println("Draw!");

} else {

System.out.println(winner.get().name + " wins!");

}

}

}

We change the type of the winner variable to Optional<Robot>. The Optional class provides the isEmpty() method, which we use to determine if we have a winner or not.

If we don’t have a winner, we still print out “Draw!”. If we do have a winner, we call the get() method on the Optional to get the winning robot and then print out its name.

Look at all the classes you created in this level and recap what would happen if you call the program.

Then, run this program and see what happens.

It should do the same as before, but we have taken advantage of some more advanced Java features to make the code more clear and less prone to accidental errors.

Don’t worry if you didn’t understand all the features we have used in detail. If you want to go through a more detailed tutorial of everything Java, you’ll want to check out the CodeGym Java tutorials.

Java Vocabulary

Phew, there were a lot of terms in the tutorial above. The following table sums them up for your convenience:

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Array | A variable type that contains multiple elements. An array can be declared by appending brackets ([]) to the type of a variable: String[] myArray;. The elements in an array can be accessed by adding brackets with the index of the wanted element to the variable name, starting with 0 for the first element: myArray[0]. |

| Attribute | A class can have zero or more attributes. An attribute is a variable of a certain type that belongs to that class. Attributes can be used like normal variables within the methods of the class. |

| Boolean | A variable type that contains either the value true or the value false. |

| Class | A class is a unit to organize code and can be used as a template to create many objects with the same set of attributes and methods. |

| Constructor | A special method that is called when we use the new keyword to create a new object from a class. It can have input parameters like any other method and implicitly returns an object of the type of the class it’s in. |

| Enum | A special class that declares an enumeration of one or more valid values. |

| Input parameter | A variable of a specific type that can be passed into a method. |

| Method | A method is a function that takes some input parameters, does something with them, and then returns a return value. |

| Null | A special value that signals “no value”. |

| Object | An object is an instance of a class. A class describes the “type” of an object. Many objects can have the same type. |

| Operator | Operators are used to compare, concatenate or modify variables. |

| Optional | A class provided by Java that signifies that a variable can have an optional value, but the value can also be empty. |

| Package | High-level unit to organize code. It’s just a folder in the file system. |

| Return value | A method may return an object of a specified type. When you call the method, you can assign the return value to a variable. |

| String | A variable type that contains a string of characters (i.e. a “text”, if you will). |

| this | A special keyword that means “this object”. Can be used to access attributes of a class in the classes' methods. |

| Variable | A variable can contain a value of a certain type/class. Variables can be passed into methods, combined with operators, and returned from methods. |

| {: .table} |

Where to Go From Here?

If this article made you want to learn more about Java, head over to CodeGym. They provide a very entertaining and motivating learning experience for Java. Exercises are embedded in stories and you can create and run code right in the browser!

And, of course, you can play around with the code examples from this article on GitHub.