In the article “Getting Started with AWS CDK”, we have already deployed a Spring Boot application to AWS with the CDK. We used a pre-configured “black box” construct named SpringBootApplicationStack, passed in a few parameters, and wrapped it in a CDK app to deploy it with the CDK CLI.

In this article, we want to go a level deeper and answer the following questions:

- How can we create reusable CDK constructs?

- How do we integrate such reusable constructs in our CDK apps?

- How can we design an easy to maintain CDK project?

On the way, we’ll discuss some best practices that helped us manage the complexities of CDK.

Let’s dive in!

Check Out the Book!

This article is a self-sufficient sample chapter from the book Stratospheric - From Zero to Production with Spring Boot and AWS.

If you want to learn how to deploy a Spring Boot application to the AWS cloud and how to connect it to cloud services like RDS, Cognito, and SQS, make sure to check it out!

The Big Picture

The basic goal for this chapter is still the same as in the article “Getting Started with AWS CDK”: we want to deploy a simple “Hello World” Spring Boot application (in a Docker image) into a public subnet in our own private virtual network (VPC). This time, however, we want to do it with reusable CDK constructs and we’re adding some more requirements:

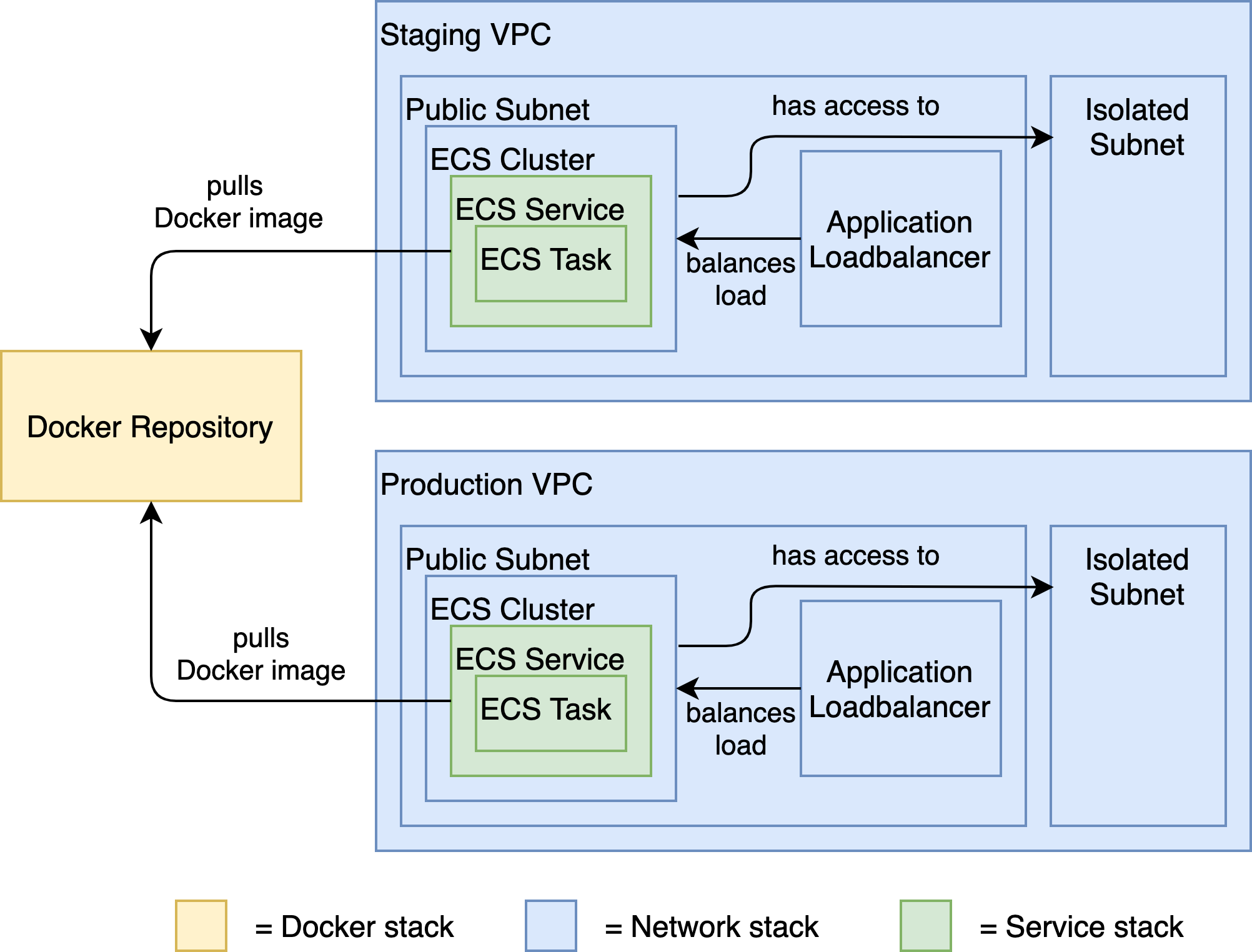

The image above shows what we want to achieve. Each box is a CloudFormation resource (or a set of CloudFormation resources) that we want to deploy. This is a high-level view. So, there are actually more resources involved but let’s not worry about that, yet. Each color corresponds to a different CloudFormation stack. Let’s go through each of the stacks one by one.

The Docker Repository stack creates - you guessed it - a Docker repository for our application’s Docker images. The underlying AWS service we’re using here is ECR - Elastic Container Registry. We can later use this Docker repository to publish new versions of our application.

The Network stack deploys a VPC (Virtual Private Network) with a public subnet and an isolated (private) subnet. The public subnet contains an Application Load Balancer (ALB) that forwards incoming traffic to an ECS (Elastic Container Service) Cluster - the runtime of our application. The isolated subnet is not accessible from the outside and is designed to secure internal resources such as our database.

The Service stack contains an ECS service and an ECS task. Remember that an ECS task is basically a Docker image with a few additional configurations, and an ECS service wraps one or more of such tasks. In our case, we’ll have exactly one task because we only have one application. In an environment with multiple applications, like in a microservice environment, we might want to deploy many ECS tasks into the same ECS service - one for each application. ECS (in its Fargate flavor) takes care of spinning up EC2 compute instances for hosting the configured Docker image(s). It even handles automatic scaling if we want it to.

ECS will pull the Docker image that we want to deploy as a task directly from our Docker repository.

Note that we’ll deploy the Network stack and the Service stack twice: once for a staging environment and once for a production environment. This is where we take advantage of infrastructure-as-code: we will re-use the same CloudFormation stacks to create multiple environments. We’ll use the staging environment for tests before we deploy changes to the production environment.

On the other hand, we’ll deploy the Docker repository stack only once. It will serve Docker images to both the staging and production environments. Once we’ve tested a Docker image of our application in staging we want to deploy exactly the same Docker image to production, so we don’t need a separate Docker repository for each environment. If we had more than one application, though, we would probably want to create a Docker repository for each application to keep the Docker images cleanly separated. In that case, we would re-use our Docker repository stack and deploy it once for each application.

That’s the high-level view of what we’re going to do with CDK in this article. Let’s take a look at how we can build each of those three stacks with CDK in a manageable and maintainable way.

We’ll walk through each of the stacks and discuss how we implemented them with reusable CDK constructs.

Each stack lives in its own CDK app. While discussing each stack, we’ll point out concepts that we applied when developing the CDK constructs and apps. These concepts helped us manage the complexity of CDK, and hopefully they will help you with your endeavors, too.

Having said that, please don’t take those concepts as a silver bullet - different circumstances will require different concepts. We’ll dicuss each of these concepts in its own section so they don’t get lost in a wall of text.

Working with CDK

Before we get our hands dirty with CDK, though, some words about working with CDK.

Building hand-rolled stacks with CDK requires a lot of time, especially when you’re not yet familiar with the CloudFormation resources that you want to use. Tweaking the configuration parameters of those resources and then testing them is a lot of effort, because you have to deploy the stack each time to test it.

Also, CDK and CloudFormation will spout error messages at you every chance they get. Especially with the Java version, you will run into strange errors every once in a while. These errors are hard to debug because the Java code uses a JavaScript engine (JSii) for generating the CloudFormation files. Its stack traces often come from somewhere deep in that JavaScript engine, with little to no information about what went wrong.

Another common source of confusion is the distinction between “synthesis time” errors (errors that happen during the creation of the CloudFormation files) and “deploy time” errors (errors that happen while CDK is calling the CloudFormation API to deploy a stack). If one resource in a stack references an attribute of another resource, this attribute will be just a placeholder during synthesis time and will be evaluated to the real value during deployment time. Sometimes, it can be surprising that a value is not available at synthesis time.

CDK has been originally written in TypeScript and then ported to other languages (e.g. C#, Python, and of course Java). This means that the Java CDK does not yet feel like a first-class citizen within the CDK ecosystem. There are not as many construct libraries around and it has some teething problems that the original TypeScript variant doesn’t have.

Having listed all those seemingly off-putting properties of the Java CDK, not all is bad. The community on GitHub is very active and there has been a solution or workaround for any problem we’ve encountered so far. The investment of time will surely pay off once you have built constructs that many teams in your company can use to quickly deploy their applications to AWS.

Now, finally, let’s get our hands dirty on building CDK apps!

The Docker Repository CDK App

We’ll start with the simplest stack - the Docker Repository stack. This stack will only deploy a single CloudFormation resource, namely an ECR repository.

You can find the code for the DockerRepositoryApp on GitHub. Here it is in its entirety:

public class DockerRepositoryApp {

public static void main(final String[] args) {

App app = new App();

String accountId = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("accountId");

requireNonEmpty(accountId, "accountId");

String region = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("region");

requireNonEmpty(region, "region");

String applicationName = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("applicationName");

requireNonEmpty(applicationName, "applicationName");

Environment awsEnvironment = makeEnv(accountId, region);

Stack dockerRepositoryStack = new Stack(

app,

"DockerRepositoryStack",

StackProps.builder()

.stackName(applicationName + "-DockerRepository")

.env(awsEnvironment)

.build());

DockerRepository dockerRepository = new DockerRepository(

dockerRepositoryStack,

"DockerRepository",

awsEnvironment,

new DockerRepositoryInputParameters(applicationName, accountId));

app.synth();

}

static Environment makeEnv(String accountId, String region) {

return Environment.builder()

.account(accountId)

.region(region)

.build();

}

}

We’ll pick it apart step by step in the upcoming sections. It might be a good idea to open the code in your browser to have it handy while reading on.

Parameterizing Account ID and Region

The first concept we’re applying is to always pass in an account ID and region.

We can pass parameters into a CDK app with the -c command-line parameter. In the app, we read the parameters accountId and region like this:

String accountId = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("accountId");

String region = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("region");

We’re using these parameters to create an Environment object:

static Environment makeEnv(String accountId, String region) {

return Environment.builder()

.account(accountId)

.region(region)

.build();

}

Then, we pass this Environment object into the stack we create via the env() method on the builder.

It’s not mandatory to explicitly define the environment of our CDK stack. If we don’t define an environment, the stack will be deployed to the account and region configured in our local AWS CLI via aws configure. Whatever we typed in there as the account and region would then be used.

Using the default account and region depending on our local configuration state is not desirable. We want to be able to deploy a stack from any machine (including CI servers) into any account and any region, so we always parameterize them.

Sanity Checking Input Parameters

It should come as no surprise that we strongly recommend validating all input parameters. There are few things more frustrating than deploying a stack only to have CloudFormation complain 5 minutes into the deployment that something is missing.

In our code, we add a simple requireNonEmpty() check to all parameters:

String accountId = (String) app.getNode().tryGetContext("accountId");

requireNonEmpty(accountId, "accountId");

The method requireNonEmpty() throws an exception with a helpful message if the parameter is null or an empty string.

That’s enough to catch a whole class of errors early on. For most parameters this simple validation will be enough. We don’t want to do heavy validations like checking if an account or a region really exists, because CloudFormation is eager to do it for us.

One Stack per App

Another concept we’re advocating is that of a single stack per CDK app.

Technically, CDK allows us to add as many stacks as we want to a CDK app. When interacting with the CDK app we could then choose which stacks to deploy or destroy by providing a matching filter:

cdk deploy Stack1

cdk deploy Stack2

cdk deploy Stack*

cdk deploy *

Assuming the CDK app contains many stacks, the first two commands would deploy exactly one stack. The third command would deploy all stacks with the prefix “Stack”, and the last command would deploy all stacks.

There is a big drawback with this approach, however. CDK will create the CloudFormation files for all stacks, even if we want to deploy a single stack only. This means that we have to provide the input parameters for all stacks, even if we only want to interact with a single stack.

Different stacks will most probably require different input parameters, so we’d have to provide parameters for a stack that we don’t care about at the moment!

It might make sense to group certain strongly coupled stacks into the same CDK app, but in general, we want our stacks to be loosely coupled (if at all). So, we recommend wrapping each stack into its own CDK app in order to decouple them.

In the case of our DockerRepositoryApp, we’re creating exactly one stack:

Stack dockerRepositoryStack = new Stack(

app,

"DockerRepositoryStack",

StackProps.builder()

.stackName(applicationName + "-DockerRepository")

.env(awsEnvironment)

.build());

One input parameter to the app is the applicationName, i.e. the name of the application for which we want to create a Docker repository. We’re using the applicationName to prefix the name of the stack, so we can identify the stack quickly in CloudFormation.

The DockerRepository Construct

Let’s have a look at the DockerRepository construct, now. This construct is the heart of the DockerRepositoryApp:

DockerRepository dockerRepository = new DockerRepository(

dockerRepositoryStack,

"DockerRepository",

awsEnvironment,

new DockerRepositoryInputParameters(applicationName, accountId));

DockerRepository is another of the constructs from our constructs library.

We’re passing in the previously created dockerRepositoryStack as the scope argument, so that the construct will be added to that stack.

The DockerRepository construct expects an object of type DockerRepositoryInputParameters as a parameter, which bundles all input parameters the construct needs into a single object. We use this approach for all constructs in our library because we don’t want to handle long argument lists and make it very explicit what parameters need to go into a specific construct.

Let’s take a look at the code of the construct itself:

public class DockerRepository extends Construct {

private final IRepository ecrRepository;

public DockerRepository(

final Construct scope,

final String id,

final Environment awsEnvironment,

final DockerRepositoryInputParameters dockerRepositoryInputParameters) {

super(scope, id);

this.ecrRepository = Repository.Builder.create(this, "ecrRepository")

.repositoryName(dockerRepositoryInputParameters.dockerRepositoryName)

.lifecycleRules(singletonList(LifecycleRule.builder()

.rulePriority(1)

.maxImageCount(dockerRepositoryInputParameters.maxImageCount)

.build()))

.build();

// grant pull and push to all users of the account

ecrRepository.grantPullPush(

new AccountPrincipal(dockerRepositoryInputParameters.accountId));

}

public IRepository getEcrRepository() {

return ecrRepository;

}

}

DockerRepository extends Construct, which makes it a custom construct. The main responsibility of this construct is to create an ECR repository with Repository.Builder.create() and pass in some of the parameters that we previously collected in the DockerRepositoryInputParameters.

Repository is a level 2 construct, meaning that it doesn’t directly expose the underlying CloudFormation attributes, but instead offers an abstraction over them for convenience. One such convenience is the method grantPullPush(), which we use to grant all users of our AWS account access to pushing and pulling Docker images to and from the repository, respectively.

In essence, our custom DockerRepository construct is just a glorified wrapper around the CDK’s Repository construct with the added responsibility of taking care of permissions. It’s a bit over-engineered for the purpose, but it’s a good candidate for introducing the structure of the constructs in our cdk-constructs library.

Wrapping CDK Commands with NPM

With the above CDK app we can now deploy a Docker repository with this command using the CDK CLI:

cdk deploy \

-c accountId=... \

-c region=... \

-c applicationName=...

That will work as long as we have a single CDK app, but as you might suspect by now, we’re going to build multiple CDK apps - one for each stack. As soon as there is more than one app on the classpath, CDK will complain because it doesn’t know which of those apps to start.

To work around this problem, we use the --app parameter:

cdk deploy \

--app "./mvnw -e -q compile exec:java \

-Dexec.mainClass=dev.stratospheric.todoapp.cdk.DockerRepositoryApp" \

-c accountId=... \

-c region=... \

-c applicationName=...

With the --app parameter, we can define the executable that CDK should call to execute the CDK app. By default, CDK calls mvn -e -q compile exec:java to run an app (this default is configured in cdk.json, as discussed in “Getting Started with AWS CDK”).

Having more than one CDK app in the classpath, we need to tell Maven which app to execute, so we add the exec.mainclass system property and point it to our DockerRepositoryApp.

Now we’ve solved the problem of having more than one CDK app but we don’t want to type all that into the command line every time we want to test a deployment, do we?

To make it a bit more convenient to execute a command with many arguments, most of which are static, we can make use of NPM. We create a package.json file that contains a script for each command we want to run:

{

"name": "stratospheric-cdk",

"version": "0.1.0",

"private": true,

"scripts": {

"repository:deploy": "cdk deploy --app ...",

"repository:destroy": "cdk destroy --app ..."

},

"devDependencies": {

"aws-cdk": "1.79.0"

}

}

Once we’ve run npm install to install the CDK dependency (and its transitive dependencies, for that matter), we can deploy our Docker repository stack with a simple npm run repository:deploy. We can hardcode most of the parameters for each command as part of the package.json file. Should the need arise, we can override a parameter in the command line with:

npm run repository:deploy -- -c applicationName=...

Arguments after the -- will override any arguments defined in the package.json script.

With this package.json file, we now have a central location where we can look up the commands we have at our disposal for deploying or destroying CloudFormation stacks. Moreover, we don’t have to type a lot to execute one of the commands. We’ll later add more commands to this file. You can have a peek at the complete file with all three stacks on GitHub.

The Network CDK App

The next stack we’re going to look at is the Network stack. The CDK app containing that step is the NetworkApp. You can find its code on GitHub:

public class NetworkApp {

public static void main(final String[] args) {

App app = new App();

String environmentName = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("environmentName");

requireNonEmpty(environmentName, "environmentName");

String accountId = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("accountId");

requireNonEmpty(accountId, "accountId");

String region = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("region");

requireNonEmpty(region, "region");

String sslCertificateArn = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("sslCertificateArn");

requireNonEmpty(region, "sslCertificateArn");

Environment awsEnvironment = makeEnv(accountId, region);

Stack networkStack = new Stack(

app,

"NetworkStack",

StackProps.builder()

.stackName(environmentName + "-Network")

.env(awsEnvironment)

.build());

Network network = new Network(

networkStack,

"Network",

awsEnvironment,

environmentName,

new Network.NetworkInputParameters(sslCertificateArn));

app.synth();

}

static Environment makeEnv(String account, String region) {

return Environment.builder()

.account(account)

.region(region)

.build();

}

}

It’s built in the same pattern as the DockerRepositoryApp. First, we have some input parameters, then we create a stack, and finally, we add a Network construct to that stack.

Let’s explore this app in a bit more detail.

Managing Different Environments

The first difference from the DockerRepositoryApp is that we now expect an environmentName as an input parameter.

Remember that one of our requirements is the ability to deploy our application into different environments like staging or production. We introduced the environmentName parameter for precisely that purpose.

The environment name can be an arbitrary string. We use it in the stackName() method to prefix the name of the stack. Later, we’ll see that we use it within the Network construct as well to prefix the names of some other resources. This separates the stack and the other resources from those deployed in another environment.

Once we’ve deployed the app with, say, the environment name staging, we can deploy it again with the environment name prod and a new stack will be deployed. If we use the same environment name CDK will recognize that a stack with the same name has already been deployed and update it instead of trying to create a new one.

With this simple parameter, we now have the power to deploy multiple networks that are completely isolated from each other.

The Network Construct

Let’s take a look into the Network construct. This is another construct from our construct library, and you can find the full code on GitHub. Here’s an excerpt:

public class Network extends Construct {

// fields omitted

public Network(

final Construct scope,

final String id,

final Environment environment,

final String environmentName,

final NetworkInputParameters networkInputParameters) {

super(scope, id);

this.environmentName = environmentName;

this.vpc = createVpc(environmentName);

this.ecsCluster = Cluster.Builder.create(this, "cluster")

.vpc(this.vpc)

.clusterName(prefixWithEnvironmentName("ecsCluster"))

.build();

createLoadBalancer(vpc, networkInputParameters.getSslCertificateArn());

createOutputParameters();

}

// other methods omitted

}

It creates a VPC and an ECS cluster to later host our application with. Additionally, we’re now creating a load balancer and connecting it to the ECS cluster. This load balancer will distribute requests between multiple nodes of our application.

There are about 100 lines of code hidden in the createVpc() and createLoadBalancer() methods that create level 2 constructs and connect them with each other. That’s way better than a couple of hundred lines of YAML code, don’t you think?

We won’t go into the details of this code, however, because it’s best looked up in the CDK and CloudFormation docs to understand which resources to use and how to use them. If you’re interested, feel free to browse the code of the Network construct on GitHub and open up the CDK docs in a second browser window to read up on each of the resources. If the CDK docs don’t go deep enough you can always search for the respective resource in the CloudFormation docs.

Sharing Output Parameters via SSM

We are, however, going to investigate the method createOutputParameters() called in the last line of the constructor: What’s that method doing?

Our NetworkApp creates a network in which we can later place our application. Other stacks - such as the Service stack, which we’re going to look at next - will need to know some parameters from that network, so they can connect to it. The Service stack will need to know into which VPC to put its resources, to which load balancer to connect, and into which ECS cluster to deploy the Docker container, for example.

The question is: how does the Service stack get these parameters? We could, of course, look up these parameters by hand after deploying the Network stack, and then pass them manually as input parameters when we deploy the Service stack. That would require manual intervention, though, which we’re trying to avoid.

We could automate it by using the AWS CLI to get those parameters after the Network stack is deployed, but that would require lengthy and brittle shell scripts.

We opted for a more elegant solution that is easier to maintain and more flexible: When deploying the Network stack, we store any parameters that other stacks need in the SSM parameter store.

And that’s what the method createOutputParameters() is doing. For each parameter that we want to expose, it creates a StringParameter construct with the parameter value:

private void createOutputParameters(){

StringParameter vpcId=StringParameter.Builder.create(this,"vpcId")

.parameterName(createParameterName(environmentName,PARAMETER_VPC_ID))

.stringValue(this.vpc.getVpcId())

.build();

// more parameters

}

An important detail is that the method createParameterName() prefixes the parameter name with the environment name to make it unique, even when the stack is deployed into multiple environments at the same time:

private static String createParameterName(

String environmentName,

String parameterName) {

return environmentName + "-Network-" + parameterName;

}

A sample parameter name would be staging-Network-vpcId. The name makes it clear that this parameter contains the ID of the VPC that we deployed with the Network stack in staging.

With this naming pattern, we can read the parameters we need when building other stacks on top of the Network stack.

To make it convenient to retrieve the parameters again, we added static methods to the Network construct that retrieve a single parameter from the parameter store:

private static String getVpcIdFromParameterStore(

Construct scope,

String environmentName) {

return StringParameter.fromStringParameterName(

scope,

PARAMETER_VPC_ID,

createParameterName(environmentName, PARAMETER_VPC_ID))

.getStringValue();

}

This method uses the same StringParameter construct to read the parameter from the parameter store again. To make sure we’re getting the parameter for the right environment, we’re passing the environment name into the method.

Finally, we provide the public method getOutputParametersFromParameterStore() that collects all output parameters of the Network construct and combines them into an object of type NetworkOutputParameters:

public static NetworkOutputParameters getOutputParametersFromParameterStore(

Construct scope,

String environmentName) {

return new NetworkOutputParameters(

getVpcIdFromParameterStore(scope, environmentName),

// ... other parameters

);

}

We can then invoke this method from other CDK apps to get all parameters with a single line of code.

We pass the stack or construct from which we’re calling the method as the scope parameter. The other CDK app only has to provide the environmentName parameter and will get all the parameters it needs from the Network construct for this environment.

The parameters never leave our CDK apps, which means we don’t have to pass them around in scripts or command line parameters!

If you have read “Getting Started with AWS CloudFormation” you might remember the Outputs section in the CloudFormation template and wonder why we’re not using the feature of CloudFormation output parameters. With the CfnOutput level 1 construct, CDK actually supports CloudFormation outputs.

These outputs, however, are tightly coupled with the stack that creates them, while we want to create output parameters for constructs that can later be composed into a stack. Also, the SSM store serves as a welcome overview of all the parameters that exist across different environments, which makes debugging configuration errors a lot easier.

Another reason for using SSM parameters is that we have more control over them. We can name them whatever we want and we can easily access them using the pattern described above. That allows for a convenient programming model.

That said, SSM parameters have the downside of incurring additional AWS costs with each API call to the SSM parameter store. In our example application this is negligible but in a big infrastructure it may add up to a sizeable amount.

In conclusion, we could have used CloudFormation outputs instead of SSM parameters - as always, it’s a game of trade-offs.

The Service CDK App

Let’s look at the final CDK app for now, the ServiceApp. Here’s most of the code. Again, you can find the complete code on GitHub:

public class ServiceApp {

public static void main(final String[] args) {

App app = new App();

String environmentName = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("environmentName");

requireNonEmpty(environmentName, "environmentName");

String applicationName = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("applicationName");

requireNonEmpty(applicationName, "applicationName");

String accountId = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("accountId");

requireNonEmpty(accountId, "accountId");

String springProfile = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("springProfile");

requireNonEmpty(springProfile, "springProfile");

String dockerImageUrl = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("dockerImageUrl");

requireNonEmpty(dockerImageUrl, "dockerImageUrl");

String region = (String) app

.getNode()

.tryGetContext("region");

requireNonEmpty(region, region);

Environment awsEnvironment = makeEnv(accountId, region);

ApplicationEnvironment applicationEnvironment = new ApplicationEnvironment(

applicationName,

environmentName

);

Stack serviceStack = new Stack(

app,

"ServiceStack",

StackProps.builder()

.stackName(applicationEnvironment.prefix("Service"))

.env(awsEnvironment)

.build());

DockerImageSource dockerImageSource =

new DockerImageSource(dockerRepositoryName, dockerImageTag);

NetworkOutputParameters networkOutputParameters =

Network.getOutputParametersFromParameterStore(

serviceStack,

applicationEnvironment.getEnvironmentName());

ServiceInputParameters serviceInputParameters =

new ServiceInputParameters(

dockerImageSource,

environmentVariables(springProfile))

.withHealthCheckIntervalSeconds(30);

Service service = new Service(

serviceStack,

"Service",

awsEnvironment,

applicationEnvironment,

serviceInputParameters,

networkOutputParameters);

app.synth();

}

}

Again, its structure is very similar to that of the CDK apps we’ve discussed before. We extract a bunch of input parameters, create a stack, and then add a construct from our construct library to the stack - this time the Service construct.

There are some new things happening here, though. Let’s explore them.

Managing Different Environments

In the Network stack, we already used an environmentName parameter to be able to create multiple stacks for different environments from the same CDK app.

In the ServiceApp, we go a step further and introduce the applicationName parameter.

From these two parameters, we create an object of type ApplicationEnvironment:

ApplicationEnvironment applicationEnvironment = new ApplicationEnvironment(

applicationName,

environmentName

);

We use this ApplicationEnvironment object to prefix the name of the stack we’re creating. The Service construct also uses it internally to prefix the names of the resources it creates.

While for the network stack it was sufficient to prefix stacks and resources with the environmentName, we now need the prefix to contain the applicationName, as well. After all, we might want to deploy multiple applications into the same network.

So, given the environmentName “staging” and the applicationName “todoapp”, all resources will be prefixed with staging-todoapp- to account for the deployment of multiple Service stacks, each with a different application.

Accessing Output Parameters from SSM

We’re also using the applicationEnvironment for accessing the output parameters of a previously deployed Network construct:

NetworkOutputParameters networkOutputParameters =

Network.getOutputParametersFromParameterStore(

serviceStack,

applicationEnvironment.getEnvironmentName());

The static method Network.getOutputParametersFromParameterStore() we discussed earlier loads all the parameters of the Network construct that was deployed with the given environmentName. If no parameters with the respective prefix are found, CloudFormation will complain during deployment and stop deploying the Service stack.

We then pass these parameters into the Service construct so that it can use them to bind the resources it deploys to the existing network infrastructure.

Later in the book we’ll make more use of this mechanism when we’ll be creating more stacks that expose parameters that the application needs, like a database URL or password parameters.

Pulling a Docker Image

The Service construct exposes the class DockerImageSource, which allows us to specify the source of the Docker image that we want to deploy:

DockerImageSource dockerImageSource =

new DockerImageSource(dockerImageUrl);

The ServiceApp shouldn’t be responsible for defining where to get a Docker image from, so we’re delegating that responsibility to the caller by expecting an input parameter dockerImageUrl. We’re then passing the URL into the DockerImageSource and later pass the DockerImageSource to the Service construct.

The DockerImageSource also has a constructor that expects a dockerRepositoryName and a dockerImageTag. The dockerRepositoryName is the name of an ECR repository. This allows us to easily point to the Docker repository we have deployed earlier using our DockerRepository stack. We’re going to make use of that constructor when we’re building a continuous deployment pipeline later.

Managing Environment Variables

A Spring Boot application (or any application, for that matter), is usually parameterized for the environment it is deployed into. The parameters may differ between the environments. Spring Boot supports this through configuration profiles. Depending on the value of the environment variable SPRING_PROFILES_ACTIVE, Spring Boot will load configuration properties from different YAML or properties files.

If the SPRING_PROFILES_ACTIVE environment variable has the value staging, for example, Spring Boot will first load all configuration parameters from the common application.yml file and then add all configuration parameters from the file application-staging.yml, overriding any parameters that might have been loaded from the common file already.

The Service construct allows us to pass in a map with environment variables. In our case, we’re adding the SPRING_PROFILES_ACTIVE variable with the value of the springProfile variable, which is an input parameter to the ServiceApp:

static Map<String, String> environmentVariables(String springProfile) {

Map<String, String> vars = new HashMap<>();

vars.put("SPRING_PROFILES_ACTIVE", springProfile);

return vars;

}

We’ll add more environment variables in later chapters as our infrastructure grows.

The Service Construct

Finally, let’s have a quick look at the Service construct. The code of that construct is a couple of hundred lines strong, which makes it too long to discuss in detail here. Let’s discuss some of its highlights, though.

The scope of the Service construct is to create an ECS service within the ECS cluster that is provided by the Network construct. For that, it creates a lot of resources in its constructor (see the full code on GitHub):

public Service(

final Construct scope,

final String id,

final Environment awsEnvironment,

final ApplicationEnvironment applicationEnvironment,

final ServiceInputParameters serviceInputParameters,

final Network.NetworkOutputParameters networkOutputParameters){

super(scope,id);

CfnTargetGroup targetGroup=...

CfnListenerRule httpListenerRule=...

LogGroup logGroup=...

...

}

It accomplishes quite a bit:

- It creates a

CfnTaskDefinitionto define an ECS task that hosts the given Docker image. - It adds a

CfnServiceto the ECS cluster previously deployed in theNetworkconstruct and adds the tasks to it. - It creates a

CfnTargetGroupfor the loadbalancer deployed in theNetworkconstruct and binds it to the ECS service. - It creates a

CfnSecurityGroupfor the ECS containers and configures it so the load balancer may route traffic to the Docker containers. - It creates a

LogGroupso the application can send logs to CloudWatch.

You might notice that we’re mainly using level 1 constructs here, i.e. constructs with the prefix Cfn. These constructs are direct equivalents to the CloudFormation resources and provide no abstraction over them. Why didn’t we use higher-level constructs that would have saved us some code?

The reason is that the existing higher-level constructs did things we didn’t want them to. They added resources we didn’t need and didn’t want to pay for. Hence, we decided to create our own higher-level Service construct out of exactly those low-level CloudFormation resources we need.

This highlights a potential downside of high-level constructs: different software projects need different infrastructure, and high-level constructs are not always flexible enough to serve those different needs. The construct library we created for this book, for example, will probably not serve all of the needs of your next AWS project.

We could, of course, create a construct library that is highly parameterized and flexible for many different requirements. This might make the constructs complex and error prone, though. Another option is to expend the effort to create your own construct library tailored for your project (or organization).

It’s trade-offs all the way down.

Playing with the CDK Apps

If you want to play around with the CDK apps we’ve discussed above, feel free to clone the GitHub repo and navigate to the folder chapters/chapter-6. Then:

- run

npm installto install the dependencies - look into

package.jsonand change the parameters of the different scripts (most importantly, set the account ID to your AWS account ID) - run

npm run repository:deployto deploy a docker repository - run

npm run network:deployto deploy a network - run

npm run service:deployto deploy the “Hello World” Todo App

Then, have a look around in the AWS Console to see the resources those commands created.

Don’t forget to delete the stacks afterwards, either by deleting them in the CloudFormation console, or by calling the npm run *:destroy scripts as otherwise you’ll incur additional costs.

Check Out the Book!

This article is a self-sufficient sample chapter from the book Stratospheric - From Zero to Production with Spring Boot and AWS.

If you want to learn how to deploy a Spring Boot application to the AWS cloud and how to connect it to cloud services like RDS, Cognito, and SQS, make sure to check it out!