When thinking about integration testing in a distributed system, you quickly come across the concept of consumer-driven contracts. This blog post gives a short introduction into this concept and a concrete implementation example using the technologies Pact, Spring Boot, Feign and Spring Data REST.

Deprecated

The contents of this article are deprecated. Instead, please read the articles about Creating a Consumer-Driven Contract with Feign and Pact and Testing a Spring Boot REST API against a Consumer-Driven Contract with Pact

Integration Test Hell

Each service in a distributed system potentially communicates with a set of other services within or even beyond that system. This communication hopefully takes place through well-defined APIs that are stable between releases.

To validate that the communication between a consumer and a provider of an API still works as intended after some code changes were made, the common reflex is to setup integration tests. So, for each combination of an API provider and consumer, we write one or more integration tests. For the integration tests to run automatically, we then have to deploy the provider service to an integration environment and then run the consumer application against its API. As if that is not challenging enough, the provider service may have some runtime dependencies that also have to be deployed, which have their own dependencies and soon you have the entire distributed system deployed for your integration tests.

This may be fine if your release schedule only contains a couple releases per year. But if you want to release each service often and independently (i.e. you want to practice continuous delivery) this integration testing strategy does not suffice.

To enable continuous delivery we have to decouple the integration tests from an actual runtime test environment. This is where consumer-driven contracts come into play.

Consumer-Driven Contracts

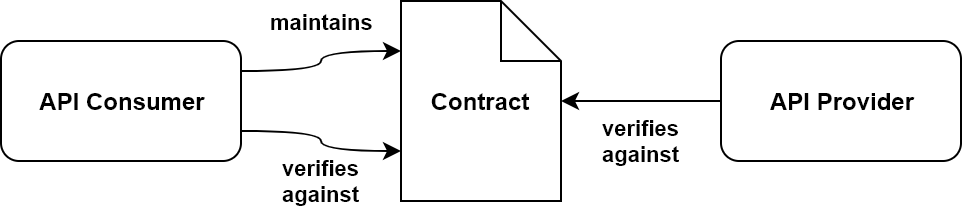

The idea behind consumer-driven contracts is to define a contract between each consumer/provider pair and then test the consumer and provider against that contract independently to verify that they abide by the contract. This way each “integration test” can run separately and without a full-blown runtime test environment.

The contract lies in the responsibility of the consumer, hence the name “consumer-driven”. For example, the consumer defines a set of requests with expected responses within a contract. This way, the provider knows exactly which API calls are actually used out there in the wild and unused APIs can safely be removed from the code base.

Of course, the contract is created by the consumer in agreement with the provider so that it cannot define API calls the provider doesn’t want to support.

The process of consumer-driven contracts looks like this:

- The API consumer creates and maintains a contract (in agreement with the provider).

- The API consumer verifies that it successfully runs against the contract.

- The API consumer publishes the contract.

- The API provider verifies that it successfully runs against the contract.

In the following sections, I will show how to implement these steps with Pact, Spring Boot, an API consumer implemented with Feign and an API provider implemented with Spring Data REST.

Pact

Pact is a collection of frameworks that support the idea of consumer-driven contracts. The core of Pact it is a specification that provides guidelines for implementations in different languages. Implementations are available for a number of different languages and frameworks. In this blog post we will focus on the Pact integrations with JUnit 4 (pact-jvm-consumer-junit_2.11 and pact-jvm-provider-junit_2.11).

Aside from Java, it is noteworthy that Pact also integrates with JavaScript. So, for example, when developing a distributed system with Java backend services and Angular frontends, Pact supports contract testing between your frontends and backends as well as between backend services who call each other.

Obviously, instead of calling it a “contract”, Pact uses the word “pact” to define an agreement between an API consumer and provider. “Pact” and “contract” are used synonymously from here on.

Creating and Verifying a pact on the Consumer Side

Let’s create an API client with Feign, create a pact and verify the client against that pact.

The Feign Client

Our API consumer is a Feign client that reads a collection of addresses from a REST API provided by the customer service. The following code snippet is the whole client. More details about how to create a Feign client against a Spring Data REST API can be read in this blog post.

@FeignClient(value = "addresses", path = "/addresses")

public interface AddressClient {

@RequestMapping(method = RequestMethod.GET, path = "/")

Resources<Address> getAddresses();

}

The Pact-Verifying Unit Test

Now, we want to create a pact using this client and validate that the client works correctly against this pact. This is the Unit test that does just that:

@RunWith(SpringRunner.class)

@SpringBootTest(properties = {

// overriding provider address

"addresses.ribbon.listOfServers: localhost:8888"

})

public class ConsumerPactVerificationTest {

@Rule

public PactProviderRuleMk2 stubProvider =

new PactProviderRuleMk2("customerServiceProvider", "localhost", 8888, this);

@Autowired

private AddressClient addressClient;

@Pact(state = "a collection of 2 addresses",

provider = "customerServiceProvider",

consumer = "addressClient")

public RequestResponsePact createAddressCollectionResourcePact(PactDslWithProvider builder) {

return builder

.given("a collection of 2 addresses")

.uponReceiving("a request to the address collection resource")

.path("/addresses/")

.method("GET")

.willRespondWith()

.status(200)

.body("...", "application/hal+json")

.toPact();

}

@Test

@PactVerification(fragment = "createAddressCollectionResourcePact")

public void verifyAddressCollectionPact() {

Resources<Address> addresses = addressClient.getAddresses();

assertThat(addresses).hasSize(2);

}

}

We add the @SpringBootTest annotation to the test class so that a Spring Boot application context -

and thus our AddressClient - is created. You could create the AddressClient by hand instead of

bootstrapping the whole Spring Boot application, but then you would not test the client that is created by Spring

Boot in production.

The PactProviderRuleMk2 is included as a JUnit @Rule. This rule is responsible for evaluating the

@Pact and @PactVerification annotations on the methods of the test class.

The method createAddressCollectionResourcePact() is annotated with @Pact and returns a RequestResponsePact.

This pact defines the structure and content of a request/response pair. When the unit test is executed, a JSON representation

of this pact is automatically generated into the file target/pacts/addressClient-customerServiceProvider.json.

Finally, the method verifyAddressCollectionPact() is annotated with @PactVerification, which tells Pact that

in this method we want to verify that our client works against the pact defined in the method

createAddressCollectionResourcePact(). For this to work, Pact starts a stub HTTP server on port 8888 which

responds to the request defined in the pact with the response defined in the pact. When our AddressClient

successfully parses the response we know that it interacts according to the pact.

Publishing a Pact

Now that we created a pact, it needs to be published so that the API provider can verify that it, too, interacts according to the pact.

In the simplest case, the pact file is created into a folder by the consumer and then read in from that same folder in a unit test on the provider side. That obviously only works when the code of both consumer and provider lies next to each other, which may not be desired due to several reasons.

Thus, we have to take measures to publish the pact file to some location the provider can access. This can be a network share, a simple web server or the more sophisticated Pact Broker. Pact Broker is a repository server for pacts and provides an API that allows publication and consumption of pact files.

I haven’t tried out any of those publication measures yet, so I can’t go into more detail. More information on different pact publication strategies can be found here.

Verifying a Spring Data REST Provider against a Pact

Assuming our consumer has created a pact, successfully verified against it and then published the pact, we now have to verify that our provider also works according to the pact.

In our case, the provider is a Spring Data REST application that exposes a Spring Data repository via REST. So, we need some kind of test that replays the request defined in the pact against the provider API and verify that it returns the correct response. The following code implements such a test with JUnit:

@RunWith(PactRunner.class)

@Provider("customerServiceProvider")

@PactFolder("../pact-feign-consumer/target/pacts")

public class ProviderPactVerificationTest {

@ClassRule

public static SpringBootStarter appStarter = SpringBootStarter.builder()

.withApplicationClass(DemoApplication.class)

.withArgument("--spring.config.location=classpath:/application-pact.properties")

.withDatabaseState("address-collection", "/initial-schema.sql", "/address-collection.sql")

.build();

@State("a collection of 2 addresses")

public void toAddressCollectionState() {

DatabaseStateHolder.setCurrentDatabaseState("address-collection");

}

@TestTarget

public final Target target = new HttpTarget(8080);

}

PactRunner allows Pact to create the mock replay client. Also, we specify the

name of the API provider via @Provider. This is needed by Pact to find the correct pact file in the

@PactFolder we specified. In this case the pact files are located in the consumer code base which lies

next to the provider code base.

The method annotated with @State must be implemented to signal to the provider which state in the pact

is currently tested, so it can return the correct data. In our case, we switch the database backing

the provider in a state that contains the correct data.

@TestTarget defines against which target the replay client should run. In our case against an HTTP

server on port 8080.

The classes SpringBootRunner and DatabaseStateHolder are classes I created myself that start up

the Spring Boot application with the provider API and allow to change the state of the underlying

database by executing a set of SQL scripts. Note that if you’re implementing your own Spring

MVC Controllers you can use the pact-jvm-provider-spring

module instead of these custom classes. This module supports using MockMvc and thus you

don’t need to bootstrap the whole Spring Boot application in the test. However, in our case Spring Data REST provides the MVC Controllers and there is no integration between Spring Data REST and Pact (yet?).

When the unit test is executed, Pact will now execute the requests defined in the pact files and verify the responses against the pact. In the log output, you should see something like this:

Verifying a pact between addressClient and customerServiceProvider

Given a collection of 2 addresses

a request to the address collection resource

returns a response which

has status code 200 (OK)

includes headers

"Content-Type" with value "application/hal+json" (OK)

has a matching body (OK)