Protecting a web application against various security threats and attacks is vital for the health and reputation of any web application. Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF or XSRF) is a type of attack on websites.

With a successful CSRF attack, an attacker can mislead an authenticated user in a website to perform actions with inputs set by the attacker.

This can have serious consequences like the loss of user confidence in the website and even fraud or theft of financial resources if the website under attack belongs to any financial realm.

In this article, we will understand:

- What constitutes a Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attack

- How attackers craft a CSRF attack

- What makes websites vulnerable to a CSRF attack

- What are some methods to secure websites from CSRF attack

Example Code

This article is accompanied by a working code example on GitHub.What is CSRF?

Modern websites often need to fetch data from other websites for various purposes. For example, the website might call a Google Map API to display a map of the user’s current location or render a video from YouTube. These are examples of cross-site requests and can also be a potential target of CSRF attacks.

CSRF attacks target websites that trust some form of authentication by users before they perform any actions. For example, a user logs into an e-commerce site and makes a payment after purchasing goods. The trust is established when the user is authenticated during login and the payment function in the website uses this trust to identify the user.

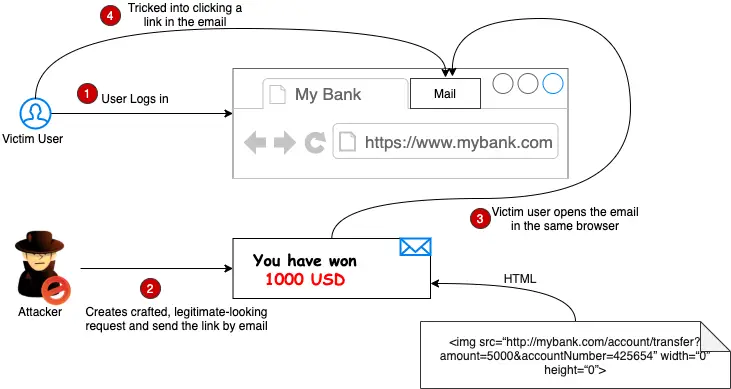

Attackers exploit this trust and send forged requests on behalf of the authenticated user. This illustration shows the making of a CSRF attack:

As represented in this diagram, a Cross-Site Request Forgery attack is roughly composed of two parts:

-

Cross-Site: The user is logged into a website and is tricked into clicking a link in a different website that belongs to the attacker. The link is crafted by the attacker in a way that it will submit a request to the website the user is logged in to. This represents the “cross-site” part of CSRF.

-

Request Forgery: The request sent to the user’s website is forged with values crafted by the attacker. When the victim user opens the link in the same browser, a forged request is sent to the website with values set by the attacker along with all the cookies that the victim has associated with that website.

CSRF is a common form of attack and has ranked several times in the OWASP Top Ten (Open Web Application Security Project). The OWASP Top Ten represent a broad consensus about the most critical security risks to web applications.

The OWASP website defines CSRF as:

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) is an attack that forces an end user to execute unwanted actions on a web application in which they’re currently authenticated. With a little help from social engineering (such as sending a link via email or chat), an attacker may trick the users of a web application into executing actions of the attacker’s choosing.

Example of a CSRF Attack

Let us now understand the anatomy of a CSRF attack with the help of an example:

- Suppose a user logs in to a website

www.myfriendlybank.comfrom a login page. The website is vulnerable to CSRF attacks. - The web application for the website authenticates the user and sends back a cookie in the response. The web application populates the cookie with the information that the user is authenticated.

- As part of a web browser’s behavior concerning cookie handling, it will send this cookie to the server for all subsequent interactions.

- The user next visits a malicious website without logging out of

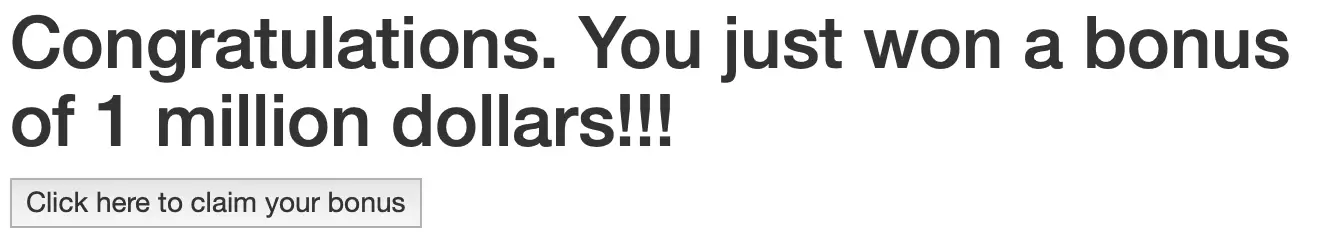

myfriendlybank.com. This malicious site contains a banner that looks like this:

The HTML used to create the banner has the below contents:

<h1>Congratulations. You just won a bonus of 1 million dollars!!!</h1>

<form action="http://myfriendlybank.com/account/transfer" method="post">

<input type="hidden" name="TransferAccount" value="9876865434" />

<input type="hidden" name="Amount" value="1000" />

<input type="submit" value="Click here to claim your bonus"/>

</form>

We can notice in this HTML that the form action posts to the vulnerable website myfriendlybank.com instead of the malicious website. In this example, the attacker sets the request parameters: TransferAccount and Amount to values that are unknown to the actual user.

-

The user is enticed to claim the bonus by visiting the malicious website and clicking the submit button.

-

On form submit after the user clicks the submit button, the browser sends the user’s authentication cookie to the web application that was received after login to the website in step 2.

-

Since the website is vulnerable to CSRF attacks, the forged request with the user’s authentication cookie is processed. Forged requests can be sent for all actions that an authenticated user is allowed to do on the website. In this example, the forged request transfers the amount to the attacker’s account.

Although this example requires the user to click the submit button, the malicious website could have run JavaScript to submit the form without the user knowing anything about it.

This example can be extended to scenarios where an attacker can perform additional damaging actions like changing the user’s password and registered email address which will block their access completely depending on the user’s permissions in the website.

How Does CSRF Work?

As explained earlier, a CSRF attack leverages the implicit trust placed in user session cookies by many web applications.

In these applications, once the user authenticates, a session cookie is created and all subsequent transactions for that session are authenticated using that cookie including potential actions initiated by an attacker by “riding” the existing session cookie. Due to this reason, CSRF is also called “Session Riding”.

Riding the Session Cookie

A CSRF attack exploits the behavior of a type of cookies called session cookies shared between a browser and server. HTTP requests are stateless due to which the server cannot distinguish between two requests sent by a browser.

But there are many scenarios where we want the server to be able to relate one HTTP request with another. For example, a login request followed by a request to check account balance or transfer funds. The server will only allow these requests if the login request was successful. We call this group of requests as belonging to a session.

Cookies are used to hold this session information. The server packages the session information for a particular client in a cookie and sends it to the client’s browser. For each new request, the browser re-identifies itself by sending the cookie (with the session key) back to the server.

The attacker hijacks (or rides) this cookie to trick the user into sending requests crafted by the attacker to the server.

Constructing a CSRF Attack

The broad sequence of steps followed by the attacker to construct a CSRF attack include the following:

- Identifying and exploring the vulnerable website for functions of interest that can be exploited

- Building an Exploit URL

- Creating an Inducement for the Victim to open the Exploit URL

Let us understand each step in greater detail.

Identifying and Exploring the Vulnerable Website

Before planning a CSRF attack, the attacker needs to identify pieces of functionality that are of interest - for example, fund transfers. The attacker also needs to know a valid URL in the website, along with the corresponding patterns of valid requests accepted by the URL.

This URL should cause a state-changing action in the target application. Some examples of state-changing actions are:

- Update account balance

- Create a customer record

- Transfer money

In contrast to state-changing actions, an inquiry does not change any state in the server. For example, viewing a user profile or viewing the account balance.

The attacker also needs to find the right values for the URL parameters. Otherwise, the target application might reject the forged request.

Some common techniques used to explore the vulnerable website are:

- View HTML Source: Check the HTML source of web pages to identify links or buttons that contain functions of interest.

- Web Application Debugging Tools: Analyze the information exchanged between the client and the server using web application debugging tools such as WebScarab, and Tamper Dev.

- Network Sniffing Tools: Analyze the information exchanged between the client and the server with a network sniffing tool such as Wireshark.

For example, let us assume that the attacker has identified a website at https://myfriendlybank.com to try a CSRF attack. The attacker explored this website using the above techniques and found a URL https://myfriendlybank.com/account/transfer with CSRF vulnerabilities which is used to transfer funds.

Building an Exploit URL

The attacker will next try to build an exploit URL for sharing with the victim. Let us assume that the transfer function in the application is built using a GET method to submit a transfer request. Accordingly, a legitimate request to transfer 100 USD to another account with account number 1234567 will look like this:

GET https://myfriendlybank.com/account/transfer?

amount=100&accountNumber=1234567

The attacker will create an exploit URL to transfer 15,000 USD to an account with account number 4567876 probably belonging to the attacker:

GET https://myfriendlybank.com/account/transfer

?amount=15000&accountNumber=4567876

If the victim clicks this exploit URL, 15,000 USD will get transferred to the attacker’s account.

Trick the Victim into Clicking the Exploit URL

The attacker then creates an enticement and uses any social engineering attack methods to trick the victim user into clicking the malicious URL. Some examples of these methods are:

- including the exploit URL in HTML image elements

- placing the exploit URL on pages that are often accessed by the victim user while being logged into the application

- sending the exploit URL through email.

The following is an example of an image with an exploit URL:

<img src=“http://myfriendlybank.com/account/transfer

?amount=5000&accountNumber=425654”

width=“0”

height=“0”>

This scenario includes an image tag with zero dimensions embedded in an attacker-crafted email sent to the victim user. Upon receiving and opening the email, the victim user’s browser will load the HTML containing the HTML image.

The IMG tag of the image will make a GET request to the link in its src attribute. Since browsers send the cookies by default with requests, the request is authenticated, even though it is sent from a different origin than the bank’s website.

As a result, without the victim user’s permission, a forged request crafted by the attacker is sent to the web application at myfriendlybank.com.

If the victim user has an active session opened with myfriendlybank.com, the application would treat this as an authorized account transfer request coming from the victim user. It would then transfer an amount of 5000 to the account 425654 specified by an attacker.

Preventing CSRF Attacks

To prevent CSRF attacks, web applications need to build mechanisms to distinguish a legitimate request by a trusted user from a forged request crafted by an attacker but sent by the trusted user.

All the solutions to build defenses against CSRF attacks are built around this principle of sending something in the request that the forged request is unable to provide. Let us look at a few of those.

Identifying Legitimate Requests with an CSRF Token

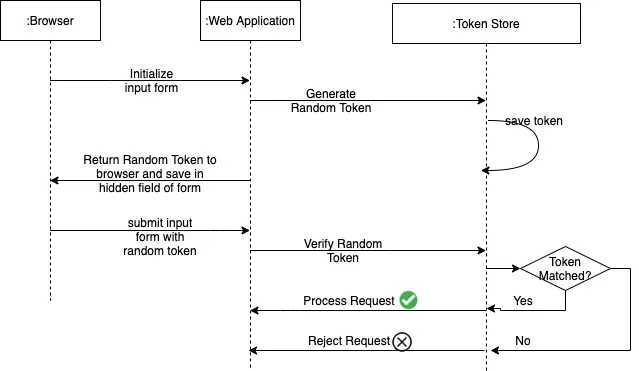

An (anti-)CSRF token is a type of server-side CSRF protection. It is a random string shared between the user’s browser and the web application. The CSRF token is usually stored in a session variable or data store. On an HTML page, it is typically sent in a hidden field or HTTP request header that is sent with the request.

An attacker creating a forged request will not have any knowledge about the CSRF token. So the web application will reject the requests which do not have a matching value of the CSRF token which it had shared with the browser.

There are two common implementation techniques of CSRF tokens known as :

- Synchronizer Token Pattern where the web application is stateful and stores the token

- Double Submit Cookie where the web application is stateless

Synchronizer Token Pattern

A random token is generated by the web application and sent to the browser. The token can be generated once per user session or for each request. Per-request tokens are more secure than per-session tokens as the time range for an attacker to exploit the stolen tokens is minimal.

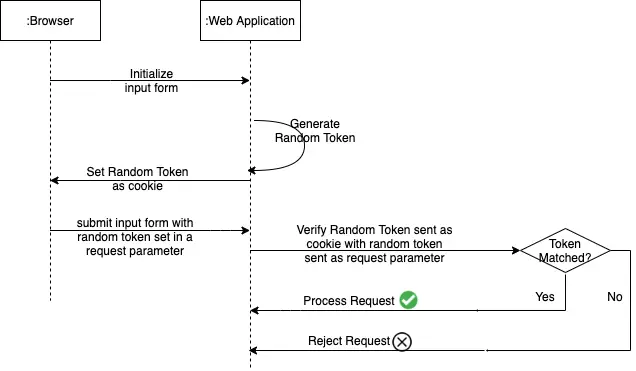

As we can see in this sequence diagram, when the input form is requested, it is initialized with a random token generated by the web application. The web application stores the generated token either in a data store or in-memory in an HTTP session.

When the input form is submitted, the token is sent as a request parameter. On receiving the request, the web application matches the token received as a request parameter with the token stored in the token store. The request is processed only if the two values match.

Double Submit Cookie Pattern

When using the Double Submit Cookie pattern the token is not stored by the web application. Instead, the web application sets the token in a cookie. The browser should be able to read the token from the cookie and send it as a request parameter in subsequent requests.

In this sequence diagram, when the input form is requested, the web application generates a random token and sets it in a cookie. The browser reads the token from the cookie and sends it as a request parameter when submitting the form.

On receiving the request, the web application verifies if the cookie value and the value sent as request parameter match. If both the values match, the web application accepts it as a legitimate request processes the request.

This cookie must be stored separately from the cookie used as a session identifier.

Using the SameSite Flag in Cookies

The SameSite flag in cookies is a relatively new method of preventing CSRF attacks and improving web application security. In an earlier example, we saw that the website controlled by the attacker could send a request to https://myfriendlybank.com/ together with a session cookie. This session cookie is unique for every user, so the web application uses it to distinguish between users and determine if they are logged in.

If the session cookie is marked as a SameSite cookie, it is only sent along with requests that originate from the same domain. Therefore, when http://myfriendlybank.com wants to make a POST request to http://myfriendlybank/transfer it is allowed.

However, the website controlled by the attacker with a domain like http://malicious.com/ cannot send HTTP requests to http://myfriendlybank.com/transfer. This is because the session cookie originates from a different domain, and thus it is not sent with the request.

Defenses Against CSRF

As users, we can defend ourselves from falling victim to a CSRF attack by cultivating two simple web browsing habits:

- We should log off from a website after using it. This will invalidate the session cookies that the attacker needs to execute the forged request in the exploit URL.

- We should use different browsers, for example, one browser for accessing sensitive sites and another browser for random surfing. This will prevent the session cookies set in sensitive sites from being used for CSRF attacks launched from a page opened from a different browser.

As developers, we can use the following best practices other than the CSRF token described earlier:

- Configure a lower session timeout value invalidate the session after a period of inactivity

- Log the user out after a period of inactivity and invalidate the session cookie.

- Seek confirmation from the user before processing any state-changing action with a confirmation dialog or a captcha.

- Make it difficult for an attacker to know the structure of the URLs to attack.

Example of CSRF Protection in a Node.js Application

This is an example of implementing CSRF protection in a web application written in Node.js using the express framework. We have used an npm library csurf which provides the middleware for CSRF token creation and validation:

const express = require('express');

const csrf = require('csurf');

const cookieParser = require('cookie-parser');

// Implement the the double submit cookie pattern

// and Store the token secret in a cookie

var csrfProtection = csrf({ cookie: true });

var parseForm = express.urlencoded({ extended: false });

var app = express();

app.set('view engine','ejs')

app.use(cookieParser());

// render the input form

app.get('/transfer', csrfProtection, function (req, res) {

// pass the csrfToken to the view

res.render('transfer', { csrfToken: req.csrfToken() });

});

// post the form to this URL

app.post('/process', parseForm,

csrfProtection, function (req, res) {

res.send('Transfer Successful!!');

});

app.listen(3000, (err) => {

if (err) console.log(err);

console.log('Server listening on 3000');

});

In this code block, we initialize the csrf library by setting the value of cookie to true. This means that the random token for the user will be stored in a cookie instead of the HTTP session. Storing the random token in a cookie implements the double submit cookie pattern explained earlier.

The below HTML page is rendered with the GET request. The random token is generated in this step:

<html>

<head>

<title>CSRF Token Demo</title>

</head>

<body>

<form action="process" method="POST">

<input type="hidden" name="_csrf" value="<%= csrfToken %>">

<div>

<label>Amount:</label><input type="text" name="amount">

</div>

<br/>

<div>

<label>Transfer To:</label><input type="text" name="account">

</div>

<br/>

<div>

<input type="submit" value="Transfer">

</div>

</form>

</body>

</html>

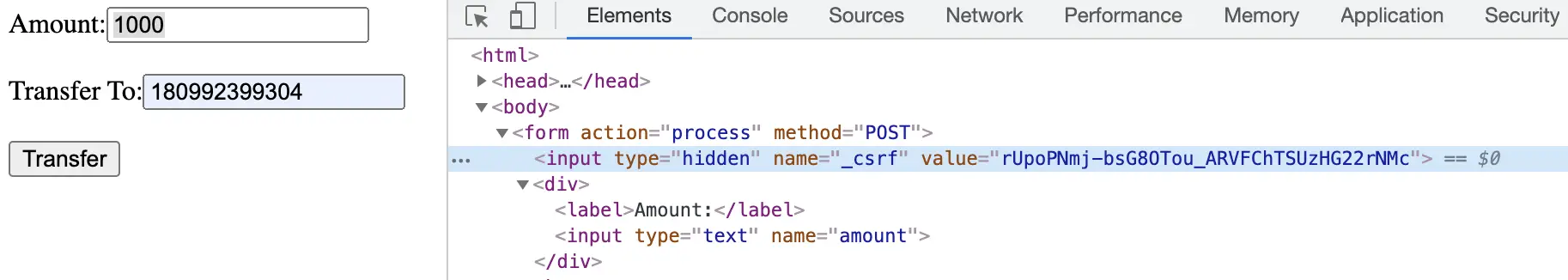

We can see in this HTML snippet, that the random token is set in a hidden field named _csrf.

After we set up and run the application, we can test a valid request by loading the HTML form with URL http://localhost:3000/transfer :

The form is loaded with the csrf token set in a hidden field. When we submit the form after providing the values of the amount and account the request is sent with the csrf token and is processed successfully.

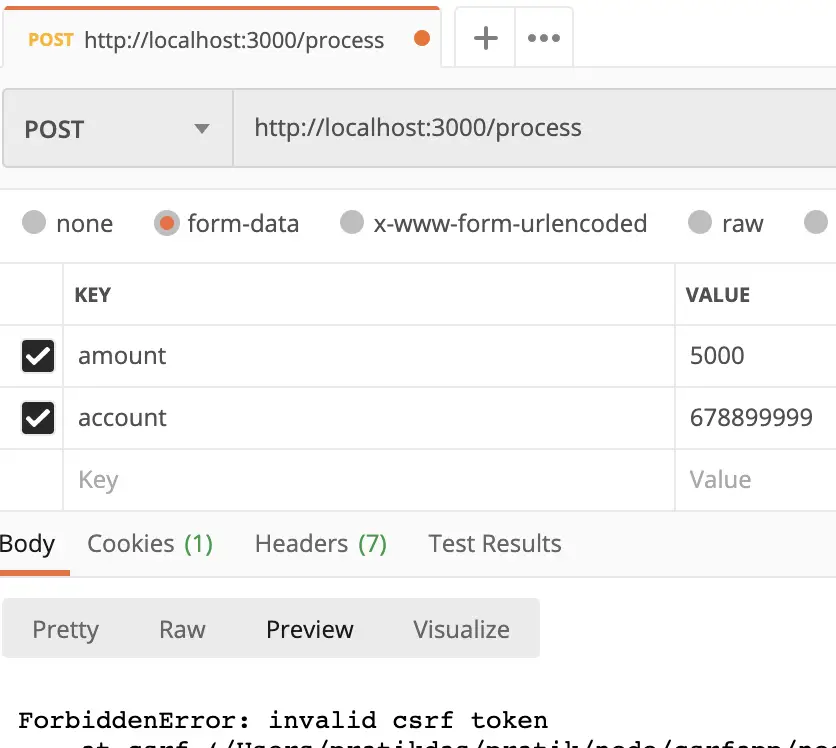

Next, we can try to send a request from Postman (or any other HTTP request tool) to simulate a forged request in a CSRF attack. The results are shown in this screenshot:

Since our code is protected with CSRF token, the request is denied by the web application with an error: ForbiddenError: invalid csrf token.

If we are using Ajax with JSON requests, then it is not possible to submit the CSRF token within an HTTP request parameter. In this situation, we include the token within an HTTP request header.

Libraries for CSRF protection similar to csurf are available in other languages. We should prefer to use a vetted library or framework instead of building our own for CSRF prevention. Some other examples are CSRFGuard and Spring Security.

Conclusion

CSRF attacks comprise a good percentage of web-based attacks. It is crucial to be aware of the vulnerabilities that could make our website a potential target for CSRF attacks and prevent these attacks by building proper CSRF defenses in our application.

Here is a list of important points from the article for quick reference:

- A CSRF attack leverages the implicit trust placed in user session cookies by many web applications.

- To prevent CSRF attacks, web applications need to build mechanisms to distinguish a legitimate request from a trusted user of a website from a forged request crafted by an attacker but sent by the trusted user.

- An (anti-)CSRF token is a random string shared between the user’s browser and the web application and is a common type of server-side CSRF protection.

- There are two common implementation techniques of CSRF Tokens known as :

- Synchronizer Token Pattern

- Double Submit Cookie

You can refer to all the source code used in the article on Github.